What Is Your Healthcare System and Why Does It Matter?

Four models rule the developed world. The U.S. system is the most inefficient.

Citizens of industrialized countries other than the United States must find the debates over healthcare in the U.S. puzzling. After all, they have had universal healthcare for many decades while the U.S. lacks any such system, despite the passage in 2010 of the Affordable Care Act (otherwise known as the ACA or Obamacare).

Of course, it is more complicated than that. The United States has some of the best healthcare services in the world for those who can gain access to them, largely through employer-sponsored private health insurance. On the other hand, Canada, which boasts of its system of universal healthcare, has some of the longest waiting times in the industrialized world for many procedures and treatments.

The fact is, neither the U.S. nor Canada has too much to boast about. In a recent study, the Commonwealth Fund ranked the healthcare systems of 11 industrialized countries.1 While the U.S. came in dead last, Canada came in just two places ahead, in ninth place. Similarly, in the World Health Organization's ranking of 190 countries, Canada is ranked 30 and the U.S. is ranked 37.2

How the healthcare system works in a country has a large impact on the financial, as well as physical, well-being of that country’s people. The systems around the world affect investors differently with respect to taxes, insurance premiums, coverage, and out-of-pocket expenses.

I believe that the best way to approach the financial aspects of health is the same as with other aspects of financial planning, through the life cycle.3 Just as human capital, financial capital, asset allocation, the need for life insurance, the role of annuities, and all other cash flows change in a systematic fashion as a person moves from beginning a career, to midcareer working years, to retirement, and finally to old-age,4the costs and needs of healthcare change as well. How well a country's healthcare system meets the needs of its citizens over the course of their lives is a major factor in that system's effectiveness.

The Economics of Health Insurance Risk Pooling Healthcare insurance, like all insurance, is based on risk pooling. In health insurance, a risk pool consists of many individuals, each of whom faces a small probability of having expensive healthcare needs. By charging each person in the pool a premium, an insurer has enough money to pay for the large healthcare costs of those few in the pool that end up needing it and pay the expenses of running the pool. If the insurer is a for-profit entity, it will set the premium high enough to make a profit.

This basic risk model has always been the basis of the private part of the U.S. health insurance system. This is why, historically, U.S. insurance companies would not accept people with pre-existing conditions into their regular plans.5To do so would increase the level of payouts and, thus, require a rise in premiums. All people with pre-existing conditions could do was to join special plans for them that had very high premiums.

The ACA outlawed rejecting people with pre-existing conditions from health insurance plans. In an attempt to keep premiums from rising, the law imposes a fine on anyone who does not purchase health insurance. In this way, healthy people join the risk pools and, thus, keep premiums down. However, because many healthy people see little benefit from having health insurance, they would rather pay the fines than buy the insurance. Hence, under the ACA, premiums are rising for those that stay insured while millions choose to remain uninsured.

Universal Coverage A solution to the problem of creating risk pools that contain enough healthy people in the mix to contain the costs of providing expensive healthcare to those who need it is to create what I call intergenerational pools. An intergenerational pool contains people from all phases of the lifecycle. In the first phase, people are generally healthy, and what they put into the system may exceed the benefits that they obtain. For older people, further down the lifecycle, healthcare needs are higher, so they may be receiving benefits worth more than what they are putting in. Each individual effectively has a lifetime healthcare insurance policy.

In all industrialized countries except the United States, intergenerational risk pools are achieved by making participation mandatory. Countries that have mandatory participation in its healthcare system are said to have universal coverage. The lack of universal coverage is what sets the U.S. apart from the rest of the industrialized world. As I discuss below, national healthcare systems that have universal coverage can differ from each other in almost every other respect.

Monopoly or Competitive Insurance Market? In some countries, rather than having private insurance companies, at least for basic services, the government sets up a monopoly single-payer.6 Proponents of single-payer systems argue that a single-payer has lower administrative costs and lacks the costs of doing business of a private insurance company, such as marketing costs. Proponents of a competitive private insurance market argue (1) the single-payer is a government bureaucracy that like any other bureaucracy seeks to maximize its budget and not allow any budget cuts,7 and (2) competition drives down costs and premiums.8

Opting Out Many proponents of universal coverage consider it a fundamental human right that should be available to all people, regardless of income or wealth. According to many who hold this view, there should be no parallel system for wealthy people where they can get better care by paying more, as is the case in the U.K.

I hold a different point of view. I do not see universal coverage as matter of rights, but rather as a matter of economics, as I have discussed. Therefore, I see nothing wrong with the existence of a parallel system of care for the wealthy. In fact, I would argue that having a parallel system for the wealthy is good for everyone else because it reduces the demand for services in the main system and, thus, reduces wait times.9

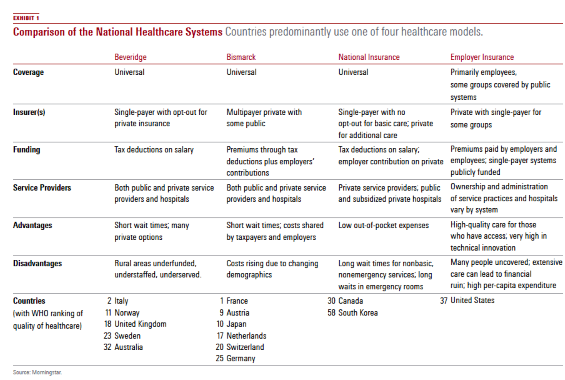

The Models Nearly all industrialized countries provide some form of universal healthcare coverage, although what is covered varies greatly between countries. In some countries, mandated coverage can be supplemented or replaced by private insurance. The one big exception to universal healthcare is the United States. The ACA was supposed to fill the gap and provide coverage for the 47 million people who had no coverage. However, 27 million people still are not covered for the reasons that I have discussed.10 There are four main healthcare models in the industrialized world (EXHIBIT 1):11

(Click image to see larger version)

Beveridge William Beveridge designed Britain's National Health Service. In this system, healthcare is provided and financed by the government through tax payments, just like the police force or the public library. Many, but not all, hospitals and clinics are owned by the government; some doctors are government employees, but there are also private doctors who collect their fees from the government. In Britain, a patient never gets a doctor bill. These systems tend to have low costs per capita, because the government, as the sole payer, controls what doctors can do and what they can charge.

Bismarck Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck invented the welfare state as part of the unification of Germany in the 19th century. This system provides healthcare using private insurance companies, called "sickness funds," which are usually financed jointly by employers and employees through payroll deduction. Health insurance plans are not-for-profit and must cover everybody. Doctors and hospitals tend to be private in Bismarck countries. (Japan has more private hospitals than does the U.S.) Although this is a multipayer model (Germany has about 240 different funds), tight regulation gives government much of the cost-control clout that the single-payer Beveridge model provides.

National Insurance This is the system used in Canada and a few other countries such as Taiwan and South Korea. It combines elements of both the Beveridge and Bismarck systems. It uses private-sector providers, but payment comes from a government-run insurance program that every citizen pays into. Because there is no need for marketing, no financial motive to deny claims, and no profit, these universal insurance programs tend to be cheaper and much simpler administratively than American-style for-profit insurance. The single-payer tends to have considerable market power to negotiate for lower prices.

Canada’s system, for example, has negotiated such low prices from pharmaceutical companies that Americans have spurned their own drug stores to buy pills north of the border. National Health Insurance plans also control costs by limiting the medical services they will pay for or by making patients wait to be treated.

Employer Insurance In the employer insurance system, people who have full-time employment receive health insurance from a private insurance company as a benefit, although they may have to pay for part of it. Depending on the policy, a wide range of services may be covered. Coverage can be in the form of traditional indemnity insurance, a preferred provider organization (PPO), or a health maintenance organization (HMO). Under indemnity insurance, patients are subject to deductions and must make copayments when receiving services. A PPO works in a similar matter, but deductions and copayments are more favorable so long as the patient stays with service providers in the PPO's network. In an HMO, coverage is limited to service providers who work for or are under contract with the HMO.

The employer insurance system only covers people with full-time jobs. In the U.S., this system is supplemented with a patchwork of governmentsponsored systems and individual markets. The government-sponsored systems include Medicare and Medicaid, which are single-payer systems, and the Veterans Administration system, which is like the U.K.'s National Health Service. Medicare is a federal program for Americans age 65 and older and for disabled Americans. Medicaid is a federal and state program for poor Americans. The VA system is, of course, for military veterans. Taken together, there are more people on Medicare and Medicaid than there are full-time private sector workers.12

The employer insurance system combined with the government-sponsor systems still leaves tens of millions of Americans uninsured. The ACA attempted to cover these individuals with new state-level insurance exchanges. But for reasons that I have discussed, many people who are eligible for insurance in their state markets are choosing to remain uninsured. Hence, universal coverage continues to elude the United States.

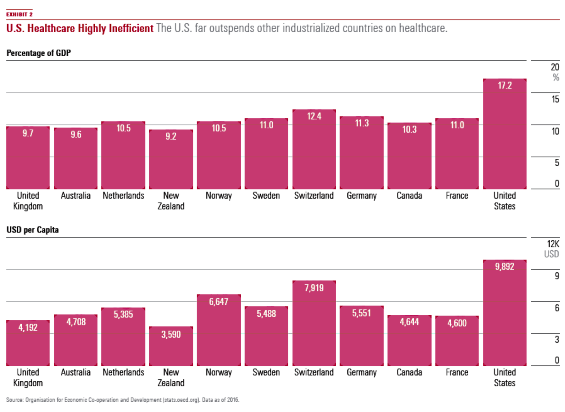

The Cost of Healthcare An important consideration in healthcare systems is how much they cost. One way is to compare healthcare expenditures between countries is to look at the percentage of gross domestic product that each country spends on healthcare. Another way is to look at healthcare spending per capita. We do both in EXHIBIT 2, which shows the 11 countries in the Commonwealth Fund study. The countries are ranked in the order presented in that study.

(Click image to see larger version)

The exhibit shows that the United States spends far more of its GDP on healthcare than the other countries. It also shows that the U.S. far outspends other developed countries on a per-capita basis. Hence, the U.S. system is not only not universal; it is also highly inefficient, taking resources from other economic activities.

A Lot to Learn In the industrialized world, the United States is the only country that lacks universal healthcare coverage. Rather, it has a hodgepodge of private and public systems that lacks the intergenerational pools needed for true lifetime coverage.13All the other systems have universal coverage, whether through a government system (Beveridge), a private system (Bismarck), or a combination of public insurance and private service providers (national insurance).

Because universal coverage is lifetime coverage, it works well with lifetime financial planning. Also, systems with universal coverage cost less per capita and as a percentage of GDP than the U.S. system and are, therefore, likely to be more economically efficient. For these reasons, U.S. policymakers have a lot that they can learn from how the rest of the industrialized world provide healthcare.

Endnotes 1 Schneider, E.C., Sarnak, D.O., Squires D., Shah, A., and Doty, M.M. 2017. "Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care," July. White paper. 2 In contrast, the Healthcare Access and Quality Index, which rates 195 countries based on mortality from causes amenable to personal healthcare, tells a different story. On this measure, Canada does reasonably well, coming in 17th, while the U.S. is ranked much further back in 35th place. The highest scoring countries are the tiny nations of Andorra and Iceland. 3 For an introduction to life-cycle analysis, see Paul D. Kaplan, "Investing Over the Life-Cycle, Part I," pp. 54–56 of this issue of Morningstar magazine. 4 For a comprehensive treatment of these matters in the context of life-cycle analysis, see Roger G. Ibbotson, Moshe A. Milevsky, Peng Chen, and Kevin X Zhu, "Lifetime Financial Advice: Human Capital, Asset Allocation, and Insurance," Charlottesville, Va.: Research Foundation of the CFA Institute, 2007. 5 In employer-sponsored plans, the insurance company could not drop individuals but could drop the company as a whole. This was the risk that a very small company faced if one of its employees developed a catastrophic health condition. 6 A number of states in the U.S. have attempted to pass legislation to create single-payer systems. 7 This is the public choice theory of professors James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock. 8 In the U.S., insurance companies cannot compete across state lines. Hence, there can be little or no competitive pressures to reduce costs and premiums. The ACA did not address this issue. 9 I thank Mark Tordai for making this point. 10 Most of the people that gained coverage did so through the expansion of Medicaid. See "Why 27 Million People Are Still Uninsured Under Obamacare," Bloomberg.com. Oct. 19, 2016. 11 I base the descriptions of the Beveridge, Bismark, and national insurance models on the Frontline documentary "Sick Around the World," which aired in April 2008. 12 Jeffrey, T.P. 2012. "Medicaid and Medicare Enrollees Now Outnumber Full-Time Private Sector Workers," Oct. 12. CNSNews.com. 13 Because Medicare is taxpayer funded (as are Medicaid and the VA), there are intergenerational transfers. But payers of the Medicare tax do not receive benefits until they are qualified by age (65 and older) or disabilities. Hence, there is no intergenerational risk pool as there is in systems that have universal coverage.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)