Statistical Illusions

Two common sources of confusion--base-rate neglect and regression to the mean.

Following the Numbers You perhaps have seen The Wall Street Journal's takedown of Morningstar's ratings systems, which appeared last week. That criticism, understandably, roiled Morningstar's powers that be, who promptly published two responses.

This article expands on the second of those commentaries, from Don Phillips. I recommend that article for those who wish to follow the WSJ-Morningstar quarrel. However, neither it nor the Journal's original piece are required reading for this column, which concerns general issues about interpreting statistics.

Base-Rate Neglect Most of the Journal's story addressed the predictive ability of the Morningstar Rating for funds, or star rating. That is not the company's only investment rating, as Morningstar also offers an equity star rating, as well as a separate "Analyst Rating" system for selected funds (mutual funds and exchange-traded funds), but it is of course the best-known. The Journal performed various before-and-after tests on the fund stars, to measure their predictive powers.

The Journal was not impressed by its findings. One pullout quote read, "Of funds with a five-star rating, three years later only 14% had performed at a five-star level." Another: "Of funds with a four-star rating, three years later 25% received only a one- or two-star rating for that period." The writers use the word "only" twice, to signal that these results were clear failures.

Statistically, that conclusion was incorrect. We cannot interpret those numbers, because we do not know the predictor's base rate. Imagine, for example, that first quote reworked, so that the subject is lottery Powerball winners, not 5-star funds. "Of that year's Powerball winners, only 14% won Powerball prizes during the next three years." Say what??? Scrap that "only"; the predictor of previous winners is hugely relevant, so much so that the fraud squad must be alerted.

In this instance, the base rate for that first quote is 10%, because 10% of funds receive the top Morningstar Rating. Thus, at 14%, the Journal's numbers demonstrated the predictive strength of the ratings, rather than the predictive weakness. Similarly, as 10% of funds receive a 1-star rating and 22.5% earn 2 stars, the news that 25% of 4-star funds subsequently scored inferior 1- or 2-star ratings meant that those funds had fared relatively well, not relatively poorly.

Monkeys and Doctors It may be objected that beating dart-throwing monkeys doesn't make a predictor successful. True, it will be conceded, 14% is better than 10%. If one wishes to push the argument, 14% is a full 40% higher than 10%--an astronomical advantage by many statistical standards. (The Vegas house edge for blackjack is less than 1%; for roulette, it ranges from 2.7% for wheels with one zero to just over 5% for wheels that also contain double zero.) But still, a 14% success rate means an 86% failure rate.

This line of thought is unhelpful, because the interpretation is driven by the definition of the base rate. It so happens that the Journal selected the top decile as defining success. But it could have opted instead for funds that placed in top third (roughly) by combining the 4- and 5-star ratings, and then the failure rate would have been much lower. Same data, different interpretation.

Base-rate neglect is widespread and afflicts even the brightest of observers. One (in)famous study showed Harvard Medical students predicting a 56% average likelihood of a hypothetical disease, when the correct answer was 2%. To cite another example, each year IBM spends several million dollars on a U.S. Open Tennis advertising campaign that features meaningless predictions from its "Watson" engine--meaningless because, with no base rates provided, its output doesn't indicate whether the player is good or bad at the analyzed task.

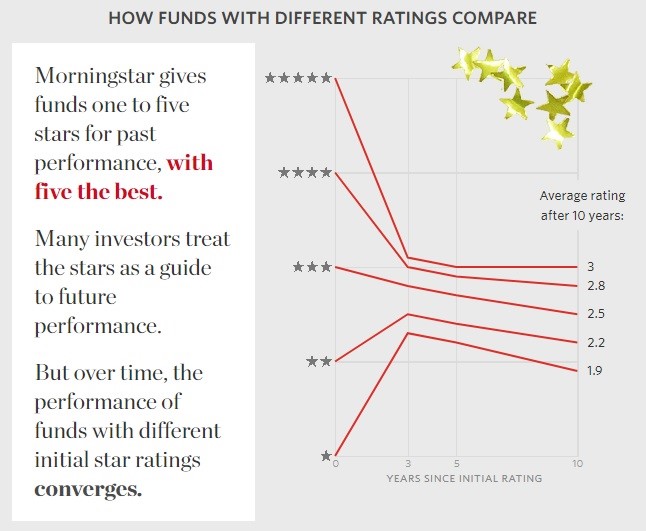

Regression to the Mean Unlike with its first statistical illusion, the Journal's second is not necessarily a mistake. Indeed, I might have printed the same chart, had I written its story:

Graphic source: The Wall Street Journal; data source: Morningstar.

The point is well taken: Star ratings converge sharply, over time. The pool of 5-star funds performs nowhere near as well as it did before the measurement was taken, the pool of 1-star funds recovers, and the 4- and 2-star pools move even closer to the middle. This is information worth knowing.

However, it is information worth knowing only in the sense of reminding readers what they already should have realized but probably had forgotten. Everything regresses to the mean. Stock performances do. Sports teams do. As Sir Francis Galton demonstrated in his initial study of the subject, so do the heights of family members. The law is general, not specific.

Thus, the chart offers no special insight into the performance of Morningstar's star ratings. By definition, any peer groups that are formed by sorting attributes that vary over time (as opposed to those that are constant, such as fund expenses, for the most part) will regress to the mean. That which was up the most will not rise higher. (As Don Phillips writes, a 5-star fund cannot become a 6-star fund.) That which was down the most will not decline further.

This, of course, is one of the most critical of investment lessons--the understanding that the highest-return securities (or asset classes) are unlikely to continue their heroics, and that the bottom dwellers may well have merit. The story of the predictability of the star ratings cannot be told without that as a backdrop. However, that analysis alone is insufficient. What matters, once again, is the base rate: How does Morningstar's predictive system stack up against other methods of prediction? They will all regress to the mean, but which will regress the least?

For more on this topic, see this 2014 column, which covers the subject from a slightly different angle.

We removed the phrase "(assisted by Morningstar, which performed the calculations at the newspaper's request)" from the sentence that now reads "The Journal performed various before-and-after tests on the fund stars, to measure their predictive powers. While Morningstar furnished the data that the Wall Street Journal used to conduct its analysis, it performed its own calculations. We regret the error.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)