Fiduciary Rule Should Be Largely Positive for Investors

In a comment letter to the SEC, Morningstar’s Aron Szapiro explores what changes the fiduciary rule has had on the asset management industry and what the SEC can do to help investors.

Although most of the attention around the future of the fiduciary rule has centered around what changes the Department of Labor might make, the SEC could also play a crucial role. Since 2010, the commission has had the authority to create a "uniform advice standard" which could apply to both retirement and nonretirement accounts. While we don't expect the SEC to promulgate a rule imminently, the DOL has pledged to work closely with the SEC on any modifications to the fiduciary rule.

New SEC Chair Jay Clayton has started the process of examining this issue by asking for responses to a series of questions about rules governing how broker/dealers and registered investment advisors can give advice. Morningstar took the opportunity to share our views on the best path forward in a letter submitted to the chair this week. The text of the letter is below and a PDF version is available here.

Dear Chairman Clayton:

Morningstar, Inc. appreciates the opportunity to comment on standards of conduct for investment advisors and broker-dealers. Morningstar, Inc. is a leading provider of independent investment research, and our mission is to create products that help investors reach their financial goals. Because we offer an extensive line of products for individual investors, professional financial advisors, and institutional clients, we have a broad view on the rule and its possible effect on the financial advice retirement investors will receive.

A Disclosure-Based Approach Is Insufficient Morningstar believes that investors' confusion about standards of conduct applicable to different kinds of relationships is likely to continue for some time, and disclosures alone will not clarify those standards for many investors. Most investors are not very experienced and probably would not invest in the absence of the defined-contribution system. For example, from our examination of the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finance, we noted that that 76% of investors invest exclusively in tax-privileged retirement plans, and these investors often do not understand fundamental investing concepts such as the importance of taking risk for long-term investing.

Further, even among experienced investors who hold investments outside of retirement accounts, most investors do not understand the distinctions between broker-dealers and Registered Investment Advisors and the conflicts of interest some financial advisors may have when recommending investments. There has also been a good deal of coverage of the recent Department of Labor "Fiduciary Rule," mostly reporting that financial advisors are now acting in the best interests of their clients, even if they were not before. Further changes in the standards would likely further confuse investors, who have absorbed the news about the Fiduciary Rule.

New, Innovative Share Classes Created in Response to the Rule Could Improve Investors' Outcomes In general, we believe the early evidence suggests the Fiduciary Rule will be positive for ordinary retirement investors, in part because the rule will reduce conflicted advice. For their part, asset managers appear to be responding to the rule by offering new share classes that should reduce conflicted advice. In the long term, we expect further innovation in share classes to provide more flexibility to advisors and better outcomes for investors. We also expect distributors to rationalize their investment lineups in response to the rule. (We have attached a recently released white paper, "Early Evidence from the Department of Labor Conflict of Interest Rule: New Share Classes Should Reduce Conflicted Advice, Likely Improving Outcomes for Investors," which provides our analysis of these share class trends.)

In particular, the Fiduciary Rule will reduce the current variation in A share sales loads. Such loads create an incentive for advisors to choose funds that might not be in an investor's best interest, but new share classes could reduce this risk. For example, with an A share, an advisor might receive a higher commission from an emerging-markets bond fund from one family rather than a lower-risk short-term bond fund from another, even if an investor would be better off with the lower-risk fund. In fact, Morningstar's database reveals a standard deviation of 1.08% on the 4.85% maximum average load. Using T shares with the same commission structure across all eligible funds, the advisor is more likely to choose the one that is best from a pure investment perspective. However, although T shares reduce conflicts in recommending a fund vis-à-vis A shares, the load still could give incentive to advisors to recommend moving money from one fund to another to collect a commission.

As we discuss in our paper, it is challenging to quantify the increased returns that investors can expect because of the shift to shares that do not create conflicts of interest from A shares, but we believe it may be around the 44.9-basis-point increase (per 100 basis points of load) the Department of Labor estimated as the benefit from reducing conflicted advice in its regulatory impact analysis. As a ballpark estimate, we think the incentives T shares create to recommend higher-quality funds could add around 50 basis points in returns--30 of which are attributable to manager skill in the form of alpha and 20 of which come from reduced fees--compared to conflicted advice. We arrived at this estimate based on the differences in returns between average funds and those with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Silver. (The potential benefits are even higher for Gold-rated funds.) Further, we think that a best-interest incentive could save investors about 20 basis points in fees as this is the typical difference between the median A share fund prospectus net expense ratio and the first quartile breakpoint. (See the attached paper for a description of the methodology and motivation.)

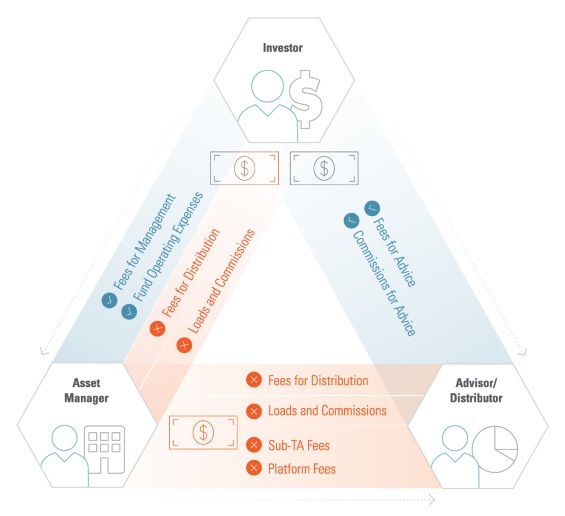

"Clean Shares" Need to Be Truly Clean to Afford Investors Proper Protections The SEC expressed interest in the financial-services industry response to the Fiduciary Rule so far, and the development of "clean shares" are among the most important innovations we have observed. These clean shares could absolutely play a role in reducing conflicts of interest in advice to investors. However, it is critical that clean shares are properly defined if regulators plan to rely on them to be the principal innovation that reduces conflicts of interest. If investors relied solely on clean shares to ensure they got conflict-free advice, they would need to be the cleanest version of clean, as illustrated in Exhibit 1. We believe truly clean shares should not permit any inducements from asset managers to advisors or distributors to offer one product over another.

Exhibit 1: Prohibited and Allowable Fees for Cleanest Shares

For the purposes of reducing conflicted advice, Morningstar believes clean share classes should create a level playing field for asset managers, so that advisors evaluate a fund on its investment quality, its role in an investor's portfolio, and its fit to the goals of the investor. Consequently, we view any part of the expense structure of a security that would cause an advisor to recommend that investment over a comparable one as precluding clean status. Accordingly, in viewing the expense structure of a clean share, we would expect to see no inducements that would make the choice of that investment more lucrative to the advisor or advisory firm than another investment, whether offered by the same asset manager or another, in the same investment style or not, and to the same investor or not. The presence of any such inducements disqualifies a fund from clean status.

Specifically, we believe that prohibited fees should include:

- Distribution fees,

- Advice fees,

- External sales charges, whether waived or not, and

- Any payment that varies by how the fund is distributed (where purchased); amount invested (breakpoints, letters of intent or rights of accumulation, and so on); or who purchases the fund (eligibility).

We also believe that clean shares should not include indirect payments of any kind to fund distributors, including third-party payments, revenue-sharing arrangements, platform fees, or finder's fees. Further, we believe the department should not permit sub-transfer-agent fees when defining clean shares. Morningstar's view is that all payments for services provided either by the distributor or to the end investor should be external to the expense structure of a clean share class so as not to create an inducement for a distributor to recommend one fund over another.

Nonetheless, we believe that with clean shares, fees for administration, advice, and so on can and should be charged in conjunction with the purchase, holding, or sale of clean share classes, but these expenses must be wholly external to the share class--that is, not embedded in the net (or gross) expense ratio. An exception would be fund-level administrative expenses that do not vary across a fund's share classes and are not paid to a distributor, such as fees for board services, which should not create an inducement.

Using this definition of clean share, we believe the Department of Labor (in partnership with the SEC) could construct a new exempted class that serves investors and reduces compliance costs for financial-services firms. The key is ensuring that the clean shares really do eliminate the risks of conflicted advice. One problem is that if the department relies on the SEC definition using rule 22-d, it would be sufficiently strong only if the disclosure and warranty requirements from the existing fiduciary rule were preserved, along with an enforcement mechanism. Those requirements, that advisory firms disclose (on a website) all arrangements that provide third-party payments to either the advisor or the financial institution and warranty that they are still providing best interest advice, would support a variety of clean share definitions because there would be ongoing scrutiny of potential conflicts of interest. However, if those requirements were dropped, and regulators were to rely on clean shares to ensure conflict-free advice, the definition we have provided would be essential.

The Rule Is Accelerating Key Trends in Retirement Investment Advice, Largely Helping Retirement Investors Achieve Their Goals In response to the questions about ongoing trends, we believe the fiduciary rule has accelerated three ongoing trends that are largely good for ordinary investors. First, we anticipate that the rule will induce some wealth management firms to move toward a fee-based model rather than selling investments on commission, as they seek to avoid using the full Best Interest Contract Exemption. We view this development as largely good for investors, although it will be important to continue monitoring developments after the rule is applicable. Fee-based arrangements largely reduce conflicts of interest because they remove incentives for advisors to favor particular investments simply because the advisor will receive a larger commission and not because it's a better-quality investment. Fee-based arrangements also improve transparency compared to opaque and varying compensation arrangements that are common when advisors sell traditional mutual fund share classes such as A shares, in which clients pay for advice indirectly through varying front-end loads and ongoing 12b-1 fees. In contrast, in fee-based arrangements retirement investors generally agree to pay a fixed percent of their assets for advice.

We anticipate that with greater transparency, advisors will need to offer advice commensurate with the fees they charge. However, in certain cases commission-based accounts may continue to better serve investors--particularly retirement savers that wish to buy and hold investments for a long period of time--because these arrangements can be less expensive. For example, if an investor paid a 2.5% commission to purchase a fund and a trailer 12b-1 fee of 0.25%, he would be better off after holding the investment for around three years (depending on returns) than if he paid a typical 1% annual management fee, assuming all else equal with regard to the investment, including the quality of advice. Ultimately, we believe the quality of advice is more important than the form in which it is paid, but making the cost of advice explicit is most likely to help retirement savers assess whether they get their money's worth for the fees they pay.

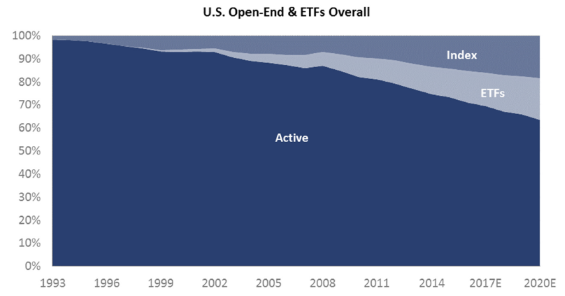

Second, we expect that the rule will accelerate the flow of assets into lower-cost index funds and exchange-traded funds and, in doing so, put more focus on the fees active mutual fund managers charge. As illustrated by Exhibit 2, index funds and (typically low-cost) ETFs have been growing in market share for years, and we expect the rule to accelerate this growth. Ultimately, with this increased focus on fund costs, more money will stay in investors' pockets, as fees are a drag on returns. Active funds can serve an important role for retirement investors, but these funds will need to compete with passive funds by demonstrating they can achieve higher (or at least uncorrelated) returns compared with passive investments. We also believe active funds will have to reduce their fees to be attractive to advisors working in the best interests of their clients.

Exhibit 2: The Total Market Share of Active, Index, and Exchange-Traded Funds and Projections

Source: Morningstar Direct

Third, the rule will create additional opportunities for digital advice solutions, which have been growing rapidly. In fact, the assets in "robo-advised" accounts at the five leading robo-advisors grew from less than $15 billion in 2014, to more than $35 billion in 2015, and to approximately $70 billion in 2016, according to our analysis of SEC data and company filings. These solutions fill the gap between no-frills discount brokerages and full-service wealth managers. They may also provide a valuable resource for investors with relatively small balances who may no longer be served by wealth managers. We view the rise of digital advice solutions as a positive for investors as these solutions are democratizing sophisticated asset-allocation models that had been available only to large institutional investors. These digital solutions will continue to evolve to address investors with more sophisticated needs.

In comments to the Department of Labor, some have argued that advisors may find providing advice to investors with relatively small balances difficult under the rule. But rather than abandoning or de-emphasizing these investors, we anticipate that the delivery of advice for this segment will change and technological innovations in the digital advice sector will fill any gap. We estimate that between $250 billion and $600 billion of assets could eventually shift from being serviced by full-service wealth management to other channels of advice, such as robo-advisors, or to hybrid solutions in which clients use a robo-advisor but have access to human advisors as well.

In summary, while greater alignment between the SEC and the Department of Labor could help investors and smooth compliance, we believe the principles-based approach the Department of Labor has pursued is largely positive for ordinary investors. In the short term, we believe the SEC can play an important role in ensuring that clean shares stay clean, and benefit individual investors, by working with the Department of Labor on their ongoing review of innovations in response to the fiduciary rule.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment.

Learn more about how Morningstar can help advisors deliver best-interest advice to investors.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)