The Morningstar Rating for Funds: A Good Starting Point for Investors?

Though it has limitations, the star rating has, on balance, pointed investors toward funds they can succeed with.

Is the Morningstar Rating for Funds, aka the star rating, a useful starting point for fund research? In this piece, which updates research we published most recently in November 2016, we'll address that question based on the evidence.

Executive Summary

- The star rating is a straightforward "report card" based on funds' trailing risk-adjusted returns.

- Like any measure that relies on past performance, the star rating has limitations; the question is whether it's a useful starting point for research that points investors in the right direction.

- To assess the star rating's usefulness, we sought to determine whether the star rating pointed investors towards funds that they would be likelier to succeed with in the future.

- On balance, we found that the star rating points investors toward cheaper funds that are easier to own and likelier to outperform in the future, qualities that correspond with investor success.

- This finding held most strongly for allocation and taxable-bond funds; star ratings of U.S. equity funds exhibited less predictive power.

Introduction The star rating is a quantitative measure that ranks funds each month based on their trailing three-, five-, and 10-year risk-adjusted returns versus their Morningstar Category peers. (Until late 2016, the star rating calculation also adjusted returns for the effects of sales commissions paid to own a fund.)

The star rating follows a bell-shaped distribution: The 10% of funds with the best rankings receive a 5-star rating; the next 22.5% get 4 stars; the 35% after that earn 3 stars; the next 22.5% receive 2 stars; and the bottom 10% of funds earn 1 star. With few exceptions, any fund that possesses a three-year track record is eligible to receive a star rating.

We launched the star rating in 1985, at a time it was common for investors to chase short-term performance and embrace gimmicky funds. Seen in that light, the star rating prefigured important investing advances, as the methodology incorporated factors like cost, risk, and investment style before they came into vogue. As these factors gained greater acceptance and the star rating achieved prominence, fund managers refocused on fees, extended their investment time horizons, and better accounted for risk in the portfolios they were assembling.

The star rating also ushered in other notable innovations, like forward-looking ratings, which intensified the focus on fees and brought new concepts, like misalignment of manager incentives, to the fore.

Background We've long believed in the merit of the straightforward, transparent approach the star rating takes to ranking funds: It's an objective "report card" on funds' past performance. By the same token, we've frequently acknowledged the star rating's limitations, which are common to any measure that relies on past performance. Since launching the star rating in 1985, we've augmented it with a host of other tools and measures and made enhancements to our methodology several times along the way.

We've encouraged users to consider combining the star rating with other data and measures to aid in fund selection. In this way, users could benefit from some of the star rating's more distinctly valuable features--that is, the way it emphasizes longer time frames, accounts for risk, and measures performance after fees and charges, considerations that don't normally figure into "leaders and laggards" tallies--while leveraging other forward-looking measures like the Morningstar Analyst Rating. In that context, we've often described the star rating as a potential starting point for research.

The question is whether it's a useful starting point for research, which we'd define as a measure that reliably guides investors toward funds they're likelier to succeed with. With that in mind, we sought to examine whether:

- The star rating points investors towards cheaper funds;

- The star rating points investors toward funds that are easier to own;

- The star rating points investors toward funds that are likelier to outperform in the future.

The scope of this analysis is all U.S. open-end mutual funds, excluding exchange-traded funds but including index funds and (unless indicated otherwise) funds of funds. The study commenced in July 2002, which was when we made the last major overhaul to the star rating methodology, and runs through May 2017.

Cheaper Arithmetically, expenses reduce investment returns basis point for basis point. Our research has also shown fees to be one of the best predictors of future performance. As such, investors are well-advised to judiciously manage costs, paying no more than they need to.

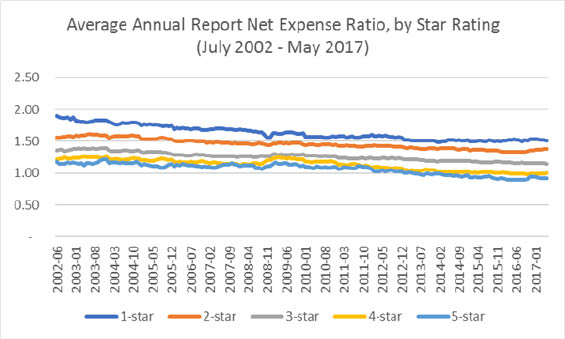

The star rating appears to advance that goal: Using funds' historical annual report net expense ratio data, we find that higher-rated funds have consistently been cheaper than lower-rated funds. Indeed, the average cost difference between 5-star and 1-star funds was nearly 0.60% during this span; that gap has not closed meaningfully even in recent periods (as of May 2017, the average 5-star fund cost 0.92%, while the average 1-star fund levied a 1.51% annual fee).

Source: Morningstar Direct; all share classes of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds, but excludes funds of funds

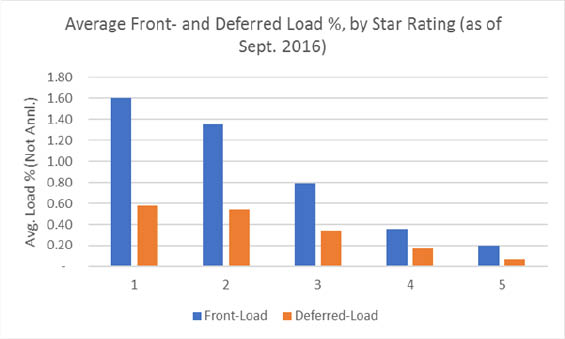

In addition, our research has found that the star rating tends to lead investors away from funds that levy sales commissions, as shown in the chart below. While there's nothing untoward about funds charging "loads" to compensate brokers for services they render in selling a fund, there's also no denying that it comes at a cost to the investor.

Source: Morningstar Direct; all share classes of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds

The star rating methodology has long taken that cost into account, as until recently it ranked funds based on their risk- and load-adjusted returns. This meant that all things being equal, a no-load fund would earn a higher ranking than a load fund every time. (In October 2016, we removed the load adjustment from the star rating methodology. We took this step because it was becoming increasingly common for funds and distributors to waive loads.)

Easier to Own Our research has also shown that investors can be prone to buying high and selling low on impulse. This can have damaging consequences, making it important to point investors toward funds they can stick with through thick and thin.

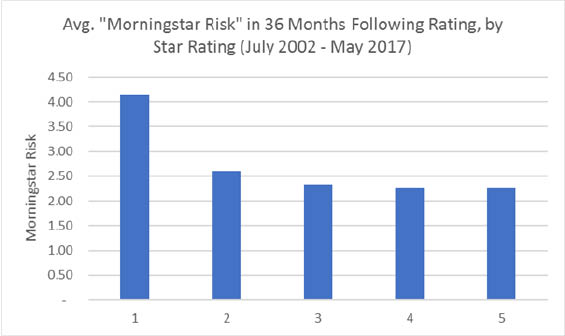

In practice, investors have tended to have a harder time sticking with more-volatile funds. With that in mind, we examined trends in the riskiness of star-rated funds and found that, on average, higher-rated funds tended to experience less dramatic downward performance spikes in the three years that followed the assignment of a star rating. (Morningstar Risk, a measure of a fund's downside return volatility, is our proxy for risk here.)

Source: Morningstar Direct; all share classes of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds

As shown in the chart, higher-rated funds tend to be less volatile subsequent to receiving a rating than lower-rated funds. This isn't tantamount to saying that 4- and 5-star funds are easier to own, but it does suggest that these funds' more-moderate risk profiles may make them less likely to rattle investors.

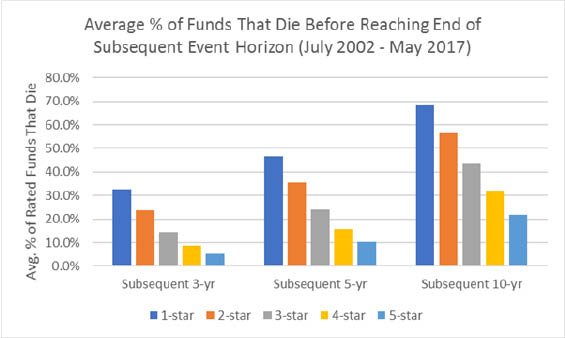

We also examined trends in fund survival by star rating. If a fund doesn't survive to the end of a subsequent event horizon, it can't be said to have been easy to own--after all, if investors in the fund must take their capital from that merged or liquidated fund and place it elsewhere, they've ceased to own it altogether. What we found was that higher-rated funds were far more likely to survive subsequent event horizons--even horizons as long as 10 years--than lower-rated funds, which died in droves.

Source: Morningstar Direct; all share classes of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds

To summarize, these findings suggest that higher-rated funds tend to suffer less downside volatility while living longer than lower-rated funds. Taken together, one could argue that those qualities make higher-rated funds easier for investors to own.

Likelier to Outperform Though we do not expect the star rating to predict future performance, it's still important to evaluate its success in sorting funds based on how they perform subsequent to receiving a star rating. The question is how to measure and evaluate subsequent performance.

In conducting previous studies of the star rating's predictiveness, we've measured subsequent performance in various ways. For instance, we've conducted sophisticated cross-sectional regressions to isolate the star rating's ability to predict the next month's return, as well as simpler tests using the event-study method. (For an example of these approaches, see our November 2016 paper, "Analyzing the Performance of the Star Rating Globally," which we'll update in the future.)

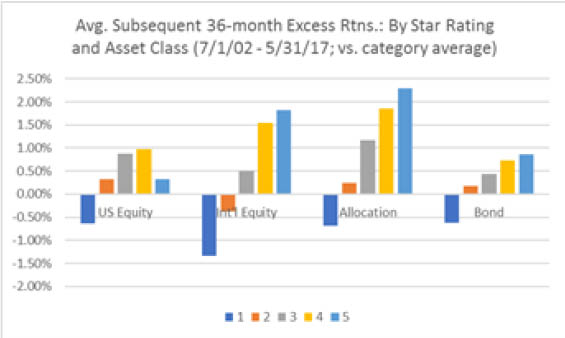

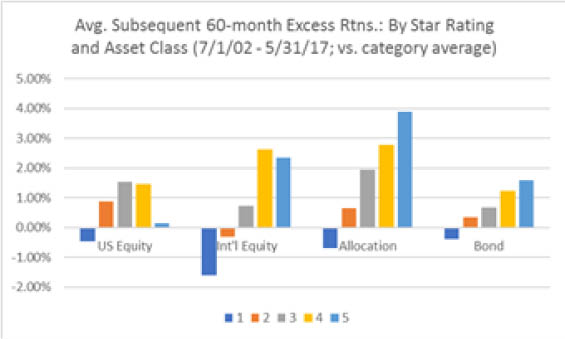

For purposes of this analysis, we opted to run a variation of the event study featured in that paper. In this case, we were interested in knowing the extent to which rated funds' subsequent returns surpassed (or lagged) the average for the category over a subsequent event horizon. Those results are shown by major asset class and star rating in the charts below.

Source: Morningstar; all share classes of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds

While the strength of the trend varied by asset class, in general high-rated funds generated higher average excess returns (versus their average category peer) than lower-rated funds in the subsequent 36- and 60-month rolling periods we examined.

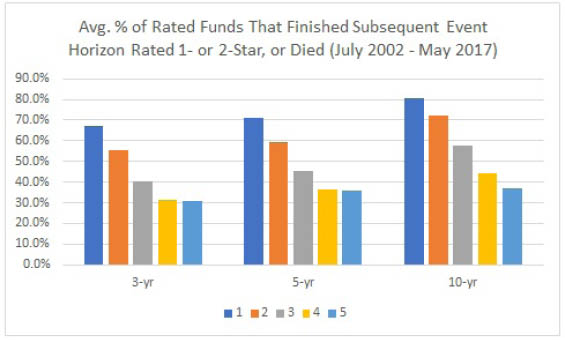

It's worth noting, however, that this test doesn't consider the level of risk these funds took in generating excess returns. Given that, we also examined the relationship between funds' star ratings and the star ratings they received subsequently. This is a meaningful test in that it measures funds based on their subsequent load- and risk-adjusted returns versus peers, not just their raw returns. In that way, it is an apples-to-apples comparison of rated funds' performance before and after they receive a star rating.

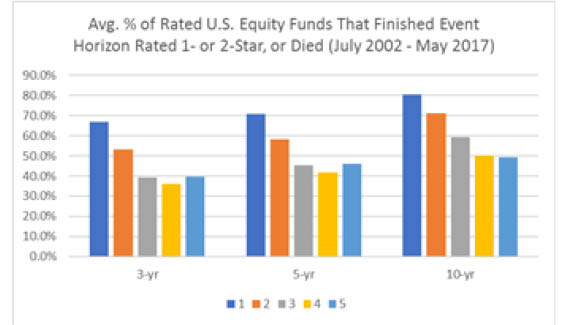

Source: Morningstar Direct; oldest share class of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds but excludes municipal-bond and alternative funds

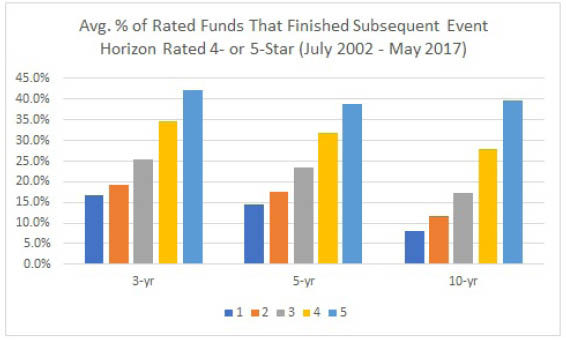

Although the results are a bit less clear-cut, it's evident that higher-rated funds are far likelier to finish a subsequent period highly rated than lower-rated funds. Such funds were also much less likely to become laggards--that is, lower-rated--in subsequent periods or to die. By contrast, low-rated funds seldom reversed their fortunes; most continued to languish as 1- or 2-star funds, if they survived at all.

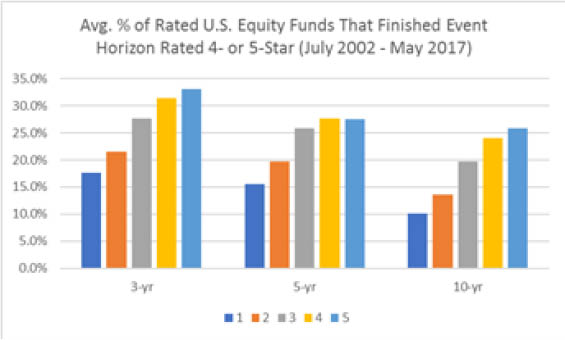

This pattern held by asset class, though the absolute level and magnitude varied: It was strongest among allocation and bond funds and weakest among U.S. equity funds, as shown below.

Source: Morningstar Direct; oldest share class of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds but excludes municipal-bond and alternative funds

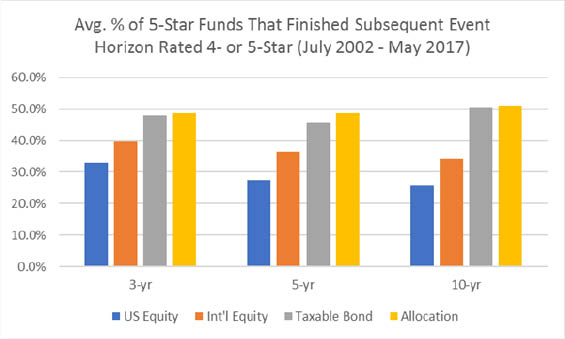

Whereas only around 26% of 5-star U.S. equity funds finished a subsequent 10-year event horizon rated 4- or 5-stars, on average, around 50% of taxable-bond and allocation funds did so, as illustrated in the chart below.

Source: Morningstar Direct; oldest share class of U.S. open-end funds; includes dead funds but excludes municipal-bond and alternative funds

Conclusion While the star rating has inherent limitations given its reliance on past performance, our analysis suggests that it can be a useful starting point for fund research. Indeed, the star rating appears to point investors toward cheaper funds that are easier to own and likelier to outperform in the future, qualities that correspond with investor success.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)