Strategic-Beta Funds Aren't as Distinctive as Advertised

Most strategic-beta funds' performance can be replicated with a combination of market-cap-weighted indexes.

Executive Summary

- Strategic-beta funds aren't as distinctive as they may first appear. It is possible to replicate most of their performance with a combination of market-cap-weighted indexes, suggesting that these funds just repackage traditional risk exposures.

- It is difficult to justify the fees that some strategic-beta funds charge, which are several times higher than what it would cost to replicate their performance with market-cap-weighted index alternatives.

- Even if their merits are sometimes exaggerated, many strategic-beta funds are still worth investing in. In many cases, it is more efficient to purchase a strategic-beta fund than trying to reassemble its underlying factor exposures, which often shift over time.

A Better Way to Invest? Most equity strategic-beta funds attempt to outperform traditional market-cap-weighted indexes through security screening, alternative weighting, or some combination of the two. These funds are often positioned as differentiated strategies with fees to match.

Yet, many of these funds simply overweight smaller and/or cheaper stocks, and investors could obtain these tilts more directly with market-cap-weighted index funds that target specific segments of the Morningstar Style Box. This leads to an important question: Can investors replicate strategic-beta funds' performance with a combination of market-cap-weighted indexes? The answer will help investors evaluate whether it is worth paying up for strategic-beta funds.

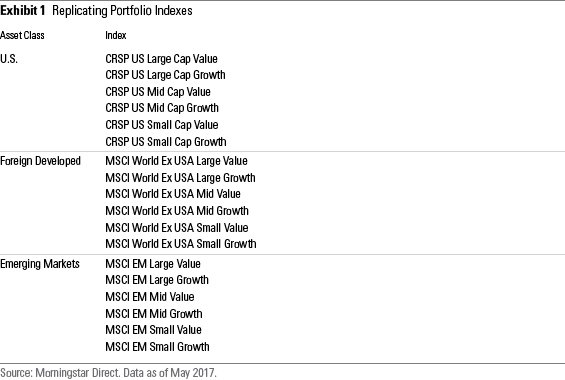

This study compares the performance of each strategic-beta fund against a replicating portfolio of six style benchmarks for its relevant universe, as shown in Exhibit 1. These replicating portfolios serve as custom benchmarks for each fund. They assign weightings to the underlying indexes that yield a portfolio whose monthly returns would have most closely mimicked those of the fund.

The purpose of these replicating portfolios isn't necessarily to recommend a substitute for the strategic-beta funds. In many cases, that wouldn't be practical because the precise weightings of the replicating portfolios are unknown ex ante, and they may shift over time. However, this analysis provides insight into whether strategic-beta funds provide exposure that's distinctive from a combination of various cap-weighted indexes.

While the CRSP U.S. indexes underpin a suite of low-cost Vanguard exchange-traded funds, there are no funds that track the foreign developed- or emerging-markets indexes listed in Exhibit 1. So, it isn't feasible for fund investors to gain access to the replicating portfolios outside the United States. It is important to note that the replicating portfolios used in this study are based on index returns and do not take fees into account.

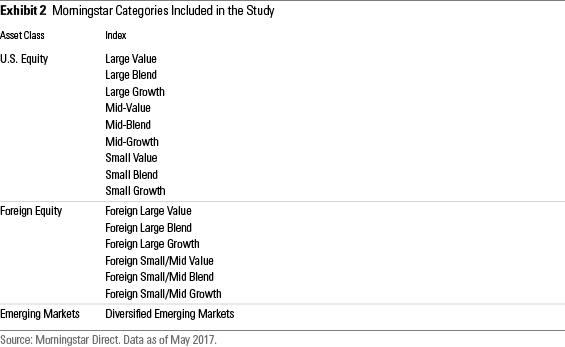

The Universe This study included all equity exchange-traded and open-end funds tagged as "Strategic Beta" in Morningstar's database, excluding market-cap-weighted value and growth funds, that were around at the beginning of June 2007 in the U.S. equity Morningstar Categories shown in Exhibit 2. I then created a replicating portfolio for each fund based on its performance during the next 10 years. The survivorship rate in each category was 100% during this span.

To expand the sample size, this study repeated the analysis for the strategic-beta funds listed at the beginning of June 2012 in the categories listed in Exhibit 2 based on their performance during the next five years. This increased the sample size to 99 funds in the United States from 65 and expanded the analysis to include foreign-equity and diversified emerging-markets equity funds. I ran the replicating portfolio analysis only on funds that survived the full period to facilitate an apples-to-apples comparison. However, survivorship rates were high in all categories.

The U.S. cohorts were by far the biggest. Of the 65 funds in the 10-year U.S. cohort, just more than half resided in one of the large-cap categories. On average, the funds in this group charged more than 4 times the highest fee that investors would have to pay to gain access to the market-cap-weighted replicating indexes. There were only 25 and 15 funds in the foreign-equity and diversified emerging-markets groups, respectively, representing a fraction of the five-year U.S. cohort's assets at the end of May 2017. However, these cohorts help to corroborate the U.S. results.

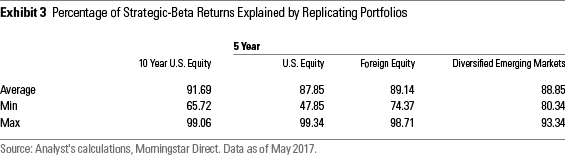

Results The replicating portfolios fit the return patterns of the strategic-beta funds well. Exhibit 3 shows the percentage of each strategic-beta fund's performance that the replicating portfolios explained, on average, in each cohort, along with the minimum and maximum values. On average, the replicating portfolios explained 92% of the return variance of the U.S. strategic-beta funds during the trailing 10 years through May 2017. And the fit was less than 85% for only eight of the 65 funds. The average fit was also high in the five-year U.S. cohort, though there were more funds (20 out of the surviving 93) whose replicating portfolios explained less than 85% of their returns. These included several growth, dividend income, and low-volatility funds. Similarly, the data for the foreign-equity and diversified emerging-markets cohorts suggests that the replicating portfolios tended to imitate the strategic-beta funds' performance well.

The fit was high for most of these funds because they did not distinguish themselves through security selection, portfolio rebalancing, or timing the size or value factors. And they did not generate differentiated performance from other factors like momentum and profitability. Rather, traditional market risk, size, and value/growth tilts could explain most of their performance.

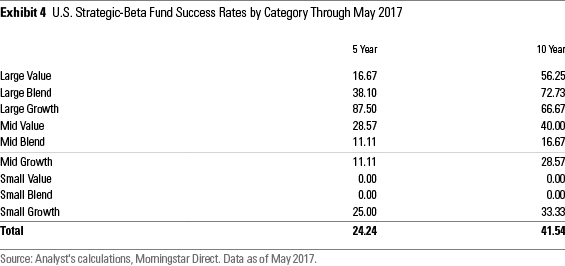

As a result, most strategic-beta funds did not outpace their replicating portfolios. Of the 65 strategic-beta funds in the 10-year U.S. cohort, 27 outperformed for an overall success rate of 42%. But 21 of these were large-cap-focused, so the corresponding success rates for the large-value, -blend, and -growth categories were all above 50%, as shown in Exhibit 4. That success rate was considerably lower in the five-year U.S. cohort. Of the 99 funds in the sample, 93 survived, but only 24 outpaced their replicating portfolios, which equates to a 24% success rate. The success rates for the foreign-equity and diversified emerging-markets funds were also below 50%, as shown in Exhibit 5, though these cohorts were smaller than the U.S. group.

Although the five-year success rate in the large-growth category looks high, the group included only eight funds.

Many strategic-beta funds' returns deviated from their replicating portfolios by considerable margins during the sample period, even though the replicating portfolios explained most of the return variance. Clearly, these return differences matter, but they could still be attributable to differences in exposure to the market, size, and value factors. If that were the case, it would suggest that even these outliers don't offer anything distinctive.

To test whether these strategic-beta funds offer distinctive performance beyond repackaging standard market, size, and value exposures, I ran a regression analysis. It attempted to explain each fund's performance using the returns of the six indexes underlying the replicating portfolios. So, if a fund simply outperformed by offering more-potent value exposure than the CRSP U.S. Large Cap Value Index, the regression wouldn't count that as anything special.

This analysis indicates that strategic-beta funds generally do not offer distinctive outperformance. Of the 65 funds from the 10-year U.S. cohort, only one had statistically significant positive returns (alpha) that could not be explained by its exposure to the six market-cap-weighted style indexes. Two additional funds had statistically significant negative underperformance. I defined statistical significance as a 5% probability that the out- or underperformance was attributable to chance. That means we would expect three of the 65 funds to come up with statistically significant alphas (positive or negative) by chance alone, consistent with our findings. In other words, the funds that did out- or underperform their replicating portfolios did so largely because of differences in their exposure to the market, value, and size factors.

The results for the other cohorts were consistent with these findings. In the five-year U.S. group, none of the 93 surviving funds had statistically significant positive alphas, but 10 had statistically significant negative alphas, twice what we would expect from chance. Fees, transaction costs, or just an unlucky draw could contribute to these funds' poor performance. In the foreign-equity and diversified emerging-markets cohorts, none of the funds had a statistically significant alpha.

Conclusion Strategic-beta funds tend to be more expensive than traditional market-cap-weighted alternatives and are often presented as a better way to invest. But this study suggests that strategic-beta funds aren't as distinctive as advertised. Most of these funds just repackage market risk, along with size and value exposures that simple cap-weighted indexes can offer. This approach can pay off, as a large minority of strategic-beta funds did outperform their replicating portfolios. However, investors shouldn't pay significantly higher fees for these strategies than market-cap-weighted alternatives, which capture the same performance drivers and can replicate most of their returns.

Even if their merits are sometimes exaggerated, many strategic-beta funds are still worth investing in. In many cases, it is more efficient to purchase a strategic-beta fund than trying to reassemble its factor exposures, which often shift over time. These dynamic tilts can make it difficult to precisely match a strategic-beta fund's factor exposures with a mix of cap-weighted funds ex ante. The case for strategic-beta funds is also stronger in foreign markets, where they may offer the most cost-efficient way to obtain certain style tilts given the dearth of market-cap-weighted value and growth index alternatives.

The full study can be found in the Research Library on Morningstar's corporate website.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)