Asking the Right Question of Index Funds

Common sense is indeed common, but it's not always sensible.

The Loser's Game?

Index funds did not take the mutual fund industry by storm. Five years after its debut,

The initial marketing was stymied by the effective, but misguided, claim made by indexing's early critics--that index funds always lose. Every active fund has the chance to beat its costless benchmark. However, index funds are guaranteed to trail. Because they mimic the costless benchmark but then add expenses (and trading costs), they inevitably fail. They lag their benchmarks, every year.

This criticism is largely true, although not entirely. Expenses do indeed drag down the returns of index funds when compared with the theoretical indexes that they track. However, as costs for the big index funds are slight and there is some fluctuation because the funds' portfolios do not exactly match the indexes', on occasion such funds will sneak past their benchmarks. For example, another Vanguard index fund, the Admiral share class of

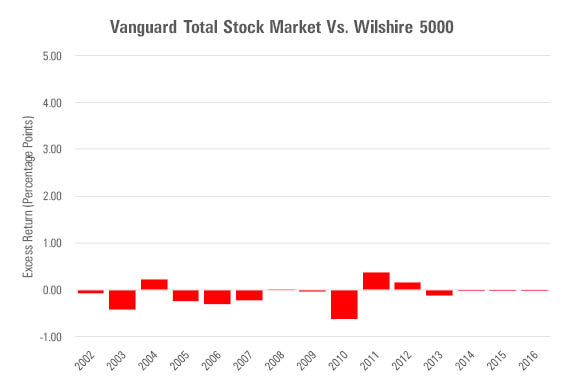

The chart would seem to support the early critics. TSM has indeed been inferior to the costless Wilshire 5000 benchmark that it simulates. (OK, technically TSM tracked the Wilshire 5000 until 2005, then for business reasons switched to a very similar index provided by the Center for Research in Security Prices.) In 15 calendar years, TSM beat Wilshire 5000 three times, tied once, and lost on 11 occasions. It didn't trail by much, to be sure, but it nonetheless did so, and will just as reliably do so in the future. In addition, it doesn't compensate for that shortfall by having lower risk than does the Wilshire 5000.

The Real World However, the comparison is flawed because investors can't buy the Wilshire 5000. Nobody can, not even the largest and most sophisticated of institutions. Those seeking broad U.S. stock market exposure can select TSM, or they can select a rival fund. The real question, therefore, is not whether TSM can beat a theoretical construct, but instead whether it beats the living, breathing funds (so to speak) that investors can purchase.

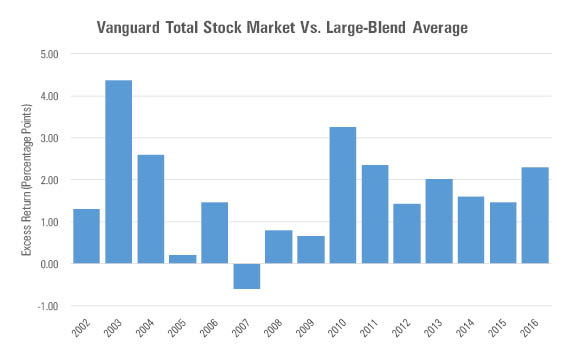

And we know how that turned out. In TSM's case, the results have outdone even the index enthusiasts' expectations:

Now we see the true case for indexing. Vanguard Total Stock Market's Admiral share class has beaten its group average (which includes other index funds as well as actively run competitors) in 14 of the past 15 calendar years. Those victories have been substantially larger than the trivial amounts by which the fund lagged the Wilshire 5000. That is, not only did switching comparisons from the index to the category average make the question relevant, it also made the answer more meaningful.

(Making TSM's triumph even more impressive is that in 2007, the only occasion on which it lost to the category average, it beat the typical rival. The fund trailed the average because a few conservatively positioned competitors performed much better than most, thereby pulling up the mean. However, it placed above the median, landing in the 47th percentile for the year.)

Indexing's Lessons This may all seem rather obvious; today, it is commonly recognized that for the major index funds, the advantages of being having lower costs and being fully, consistently invested outweigh the minor imperfections that are introduced by implementing the strategy. However, the lessons are timeless and, I think, not as widely known.

1) Much investment "common sense" is not. By definition, index funds are losers, since they can't beat the indexes that they track. You can't beat the averages by being average. You get what you pay for. Automated strategies work great during bear markets, but when the times get tough, you need a human hand. All common sense, right?

Not so. Yes, those sentences each sound reasonable upon their first hearing, and if not examined too closely. I have heard each of them delivered at investment conferences, multiple times, generally with great success. The audience nodded appreciatively; there were few if any murmurs in protest, and no awkward questions posed to the speakers.

Yet each bromide is wrong. As we saw, index funds are indeed by definition losers, but that definition happens to be unimportant. That something happens to be true doesn't make it significant. As for the notion that index funds can't beat the average by being average, that claim relies on the listener misunderstanding the facts. Index funds are average (or close to) before expenses are subtracted, but they are above average afterward.

As Jack Bogle likes to point out, investments differ from other consumer purchases in that you don't get what you pay for. Instead, you get what you don't pay for, because every penny of expenses comes straight from a fund's returns. The bumper-sticker slogan is exactly 100% wrong. Finally, while it seems reasonable that tough times require a human hand, there's no evidence from multiple bear markets that investment managers can identify bear markets before they occur and profit from that knowledge.

2) Expedience is a powerful force. All right, you probably knew that part, too. Before Caesar and Christ were born, Demosthenes wrote that the easiest mistake is self-deceit, because man believes what he wishes to be true. That belief is particularly strong when it pays in cash. Active portfolio managers are, on the whole, very bright people, and probably more ethical than most employees in most industries (my readers, of course, being happy exceptions). But they are severely compromised when discussing the demerits of index strategies. I am constantly surprised that their comments receive the attention that they do.

Speaking of which, Renaud de Planta, managing partner of a European asset management firm, recently wrote that if most investors "embrace index-trackers," they threaten to sabotage the entire economic system. Much like antibiotics, if passive funds are overused, they will create more problems than they solve.

That comparison seems … a stretch.

3) Misperceptions can and do persist for a long time. It required 80 years for the effect of mutual fund expenses to be fully appreciated. Mutual funds first came to prominence in the 1920s, but it wasn't until the mid-2000s that low-cost funds consistently outsold high-cost funds. (Today, the cost argument has won completely, as almost every new fund share carries significantly below-average expenses.) Investors learned the benefits of indexing more rapidly, but even indexing took 20 years to move from the fringe to the mainstream.

In short, the mutual fund industry remains something of a story business. It is less so than most other financial offerings, such as hedge funds or insurance products, which are less transparent. It is also less so than in the past, thanks to decades' worth of evidence and extensive academic (and industry) research. But it remains an industry where stories are told--stories that sound convincing on the surface, and that may well convince those who tell them, but which cannot withstand close analysis.

Listener beware.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)