The Powerful Force: Reversion to the Mean

How it affected hedge fund performances—and might affect ETFs.

What's Different? On June 6, Jeff Ptak explained that Morningstar is changing its policy for hedge funds that convert into mutual funds. Currently, Morningstar calculates and publishes the pre-conversion track records, if the SEC permits that data to be included in the fund's prospectus. Going forward, Morningstar will stop showing those figures, because they have misled. The former hedge funds have behaved quite differently after becoming mutual funds.

Jeff’s article suggests several potential causes for this. The converted funds might have been constrained by the Investment Company Act of 1940, which prohibits investments and strategies that are commonly used by hedge funds. They might have been slowed by a flood of new assets—the hope of which, after all, is why the funds converted in the first place. Or, perhaps, the funds stayed mostly the same, but the financial markets changed.

Those are all possible but unverifiable. As outsiders, we can’t know if those factors have affected the funds’ performances, because we don’t know how the funds were managed before their conversions. At best, those funds appear as total-return numbers in a hedge fund database—superficial data that do not address the important questions. At worst, the funds weren’t even in databases at all, as hedge fund reporting is voluntary.

Also unverifiable but surely important has been a general factor, rather than one that is specific to this case: reversion to the mean. That which has been good will likely fall. That which has been bad will likely rise. If not as immutable as gravity, reversion to the mean is as close to a natural law as exists in investment science.

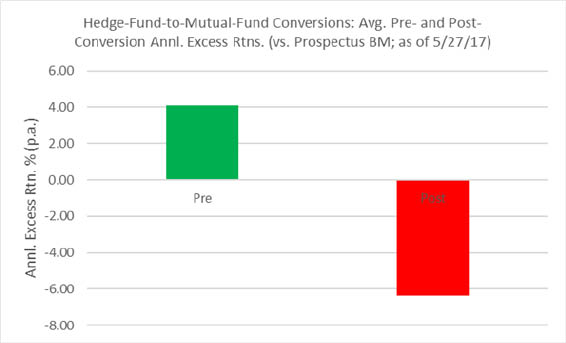

In the Red A quick review of the numbers from Jeff's second chart:

Source: Morningstar.

The green bar shows the average annual excess return (defined as the fund’s total return minus that of its benchmark index, as specified by its prospectus) of 34 hedge funds, before they converted into mutual funds. Four percentage points per year! The red bar then indicates how those funds performed post-conversion.

Oh, dear. The newly minted funds lagged their indexes by more than 600 basis points per year. And the news gets even worse. For one, that red bar would be larger yet had several of the funds not benchmarked themselves to fixed-income indexes. Easily clearing a low hurdle doesn’t make one an especially high jumper. Also, one third of those funds have expired. They entered the mutual fund marketplace, advertised their wares, took investor monies, and…quit.

Not a Random Event Reversion to the mean, of course, affects mutual funds that were born into the industry. Most winning funds, whether converted or not, have futures that are less glamorous than their histories. That is why the SEC requires that mutual funds warn that "past performance does not guarantee future results" (a statement often misquoted as being the stronger claim that "past performance does not indicate future results"), and why the performance-based Morningstar Ratings for funds (the star ratings) are, at best, only loosely predictive. Outliers drift toward the middle.

However, as demonstrated by the green and red bars, the effect is much stronger for converted hedge funds. If you take a random sample of 34 mutual funds, that group is no more likely to have beaten their aggregate benchmarks by an average of 400 basis points than you are to win the lottery tomorrow, then promptly be struck by lightning. That the former hedge funds accomplished this feat suggests just how unusual they were. They were not typical of their breed; they were well above the norm.

(Which—spoiler alert!—reminds me of the best line in the new "Wonder Woman" film. The heroine, having grown up among Amazons, has never seen a man until Chris Pine’s character crash-lands on her island. Transfixed, she asks him, “Would you say you are typical of your sex?” Well no, Mr. Pine is not; that is why he was cast in the role. After a short pause, his character replies: “I am above average.”)

The self-selection fully explains the length of the green bar. Perhaps those funds were all managed by abnormally skilled portfolio managers, or perhaps they were run by the monkeys who threw the most fortunate of darts. From the outside, we can’t know which was the case. What we do know is that three sorts of hedge funds exist: those with excellent track records, those with average records, and those with poor records. And that only funds from the first category will convert.

The red bar is trickier to decipher. If the hedge fund managers possessed skill, then reversion to the mean should have lowered their future excess returns, but not turned them deeply negative. The skill should have still persisted, to some extent. And if the managers had no skill at all and were instead handsome, nattily dressed versions of dart-throwing monkeys, then their funds’ expected excess returns would be neutral before expenses, modestly negative after expenses. Not 600 basis points to the bad.

Relative Risks Two things are going on here.

First, the excess-return calculation is very noisy. That is, because the funds invest very differently than do their benchmarks, they swing from crushing their indexes one year to trailing by 10 or 15 percentage points in another year, regardless of the quality of their managers’ decisions. The benchmarks are misfits, which makes the excess-return output partially a case of garbage in, garbage out.

(In which case, it can be argued that Morningstar is unfairly criticizing these funds for flopping after their conversions. If the excess-return measurement is used to gauge success, and that statistic is flawed, then surely that criticism also stands on shaky ground. Fair enough. But may I point out that when they operated as hedge funds, these funds were delighted to promote their excess returns, and expressed no such reservations about their usage?)

The other, related item is that these 34 funds (now 23, after the 11 expirations) run idiosyncratic portfolios. They might protect against absolute risk, but as a group they are very willing to assume relative risk—to look unlikely not only any conceivable benchmark, but also their competitors. Such a sword cuts both ways.

Lessons for ETFs The hedge fund conversion experience carries a lesson for exchange-traded fund investors. As with the converted hedge funds, infant ETFs boast impressive track records, courtesy of back-testing. Also as with the converted hedge funds, those ETFS survived a selection system. The sponsor of a niche ETF fund does not randomly choose one of the many thousands of potential investment strategies. Rather, it sifts and sorts and culls, seeking that which can be brought to market successfully. As do those sponsors that convert hedge funds into mutual funds.

However, unlike with the converted hedge funds, most ETFs don’t take on much relative risk. They tend to be highly diversified and benchmark-conscious. Thus, while I expect reversion to the mean to erase most or all of the superiority that they claim via their back-tests, I don’t expect the bottom to fall out of their excess returns, as happened with converted hedge funds.

In summary, investors can trust ETF back-tests more than they can trust hedge fund records. But not too much more.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)