Working Longer: Good Aspiration, but Not a Plan

Many Americans expect to close retirement plan gaps by working longer, but the strategy comes with its own risks, says Morningstar contributor Mark Miller.

Many older Americans, asking how they'll be able to afford retirement, have settled on an answer: Work longer, or never stop working at all.

Working longer can make sense as a way to mitigate the risks of rising longevity and declining guaranteed income from pensions and Social Security. Adding even a few years of work creates opportunities to save more, spread savings against fewer years of retirement, and boost monthly Social Security income via delayed filing credits. It can be a very big inflection point in achieving retirement security.

But working longer isn't a panacea. Research shows that about half of retirees leave the labor force earlier than they expected due to health issues, job loss, or the need to care for a loved one. When older workers seek new jobs they often face age discrimination, and those who do find work usually see their incomes fall sharply. Perhaps most unrealistic is the idea of "working forever." The numbers tell us that occurs rarely.

"People should probably think that they will work a little longer than their parents did, but it's always good to have a backup," says Richard Johnson, who directs the Urban Institute's Program on Retirement Policy and has studied extensively labor trends among older workers. "What happens if you lose your job or get sick? If possible, have a contingency plan."

The idea of working longer isn't new, notes Kerry Hannon, an expert on career transitions and work, and author of Great Jobs for Everyone 50+.

"Many retirees have worked over the years, some for money, some for the fun of it," she said. "What's different today is that work has become a pillar of retirement plans, along with Social Security, retirement accounts and saving."

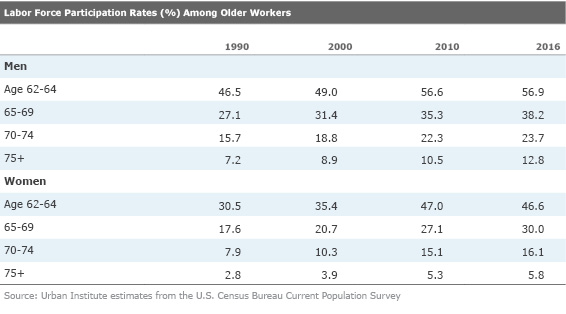

Indeed, labor participation rates have jumped substantially among men and women in their 60s and earlier 70s.

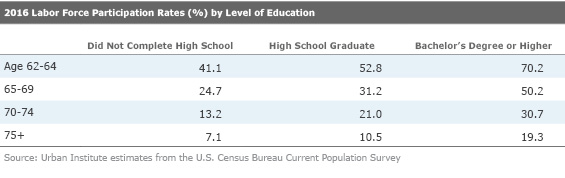

For example, 38% of men age 65 to 69 were working last year, compared with 27% in 1990, according to an analysis by Johnson of U.S. Census Bureau data; for women, the comparable participation rate jumped to 30% from 18%. And participation rates are considerably higher for more educated workers, who tend to enjoy better health and work in less physically demanding jobs.

But that doesn't mean workers are keeping their noses to the same old grindstones. Job changes are common at older ages--50% of workers employed at age 50 subsequently move to a different employer by age 70, and 60 percent move into a new occupation, according to research by Johnson based on the government-sponsored Health and Retirement Study.

Some of that, no doubt, is due to the lingering effects of the Great Recession. And many job changers report higher levels of satisfaction with their new work--either because it is more meaningful or because it comes with more flexible hours. Yet the total number of working hours tend to fall, and wages decline by half, Johnson reports. Older job-seekers also are likely to encounter age discrimination as they hunt for employment: In an AARP survey conducted in 2014, 57% of workers ages 45 to 70 who had been unemployed identified age as a barrier to finding work.

"Ageism is alive and well in the workplace," Hannon says. "Hiring managers judge a book by its cover."

What's more, the notion that "working forever" is a solution to a retirement shortfall doesn't square with reality for most of us. Some people do work to an advanced age and the numbers are growing, albeit from a small base. But it's mostly "creative class" folks who are highly motivated to continue their occupations, rather than people who need to work for the money.

Johnson's research shows that the labor force participation rate for people age 70-74 last year was 24% for men, and 16% for women; the number falls to 13% for men over age 75, and 6% of women (see first chart, above).

"People who say that they'll work forever haven't really thought about it very much," he says.

A more realistic approach is to think of work as a fluid element of retirement security, an element that may start and stop along the way, but nonetheless provides an important source of income along the retirement span--and a source of satisfaction.

"When we ask people why they plan to work longer, the answer is split just about evenly between those who want to work for enjoyment and due to financial need," says Jen Schramm, a senior strategic policy adviser at the AARP Public Policy Institute.

The drive for purpose and engagement is reflected, for example, in the encore career movement, which focuses on helping older workers transition to socially meaningful second acts. A survey by Encore.org of 1,700 adults age 50 to 70 found that 28% are "highly interested" in encore careers; and 55% see this time of life as a time where they can use personal skills and experience to help others.

Self-employment or entrepreneurship also has come to play an important role. Among workers who change employment after age 50, for example, the share of those working for themselves rises from 17 percent to 23 percent.

Hannon is a big fan of a more flexible approach.

"Don't have your heart set on a full-time job," she advises. "There are great part-time, contract, and temporary jobs out there, and, in fact, employers prefer to hire for these positions, for the obvious reasons. They also love experienced workers because you can hit the ground running and solve their problems now without training.

"Small businesses, small associations, startups, and nonprofits look for experience to lend some ballast, and they can't afford full-freight workers. These kinds of jobs aren't a bad deal for older workers either, particularly if you have health benefits from a partner who is still employed, or have reached 65 and have Medicare."

Finally, Hannon advises looking at working longer as a process that usually will have twists and turns.

"Nothing is forever--you will probably do lots of different jobs in the years ahead. It's patchwork quilt time, so be open-minded. Look at work as an adventure at this stage--one that also helps provide a financial cushion."

Mark Miller is a retirement columnist and author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work, and Living. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)