Europe Gaining Ground on U.S. Growth Rates

U.S. GDP is looking ugly in the short run, while Europe is making a comeback against the odds.

This week’s economic data seemed to suggest stabilization, if not outright economic improvements in Europe and China. In the meantime, the list of apparent woes in the U.S. increased again, with industrial production for manufacturing joining last week’s shocking retail sales decline and surprising return to deflationary CPI data.

We aren’t sweating those soft U.S. reports, just as we weren’t jumping up and down over a couple of really strong reports earlier in the year. Using year-over-year averaged data for retail sales, industrial production and inflation are all within recent trends or even slightly improved. We always worry about months with 31 days that can often cause weird average daily sales results. We continue to believe that the number of paychecks in a month and not the number of shopping days would provide a fairer selling-day adjustment. A shifting Easter holiday and unusually warm weather in February and a much more normal March are wreaking havoc with the month-to-month data sets in the U.S. for anything that depends on the weather, especially utility usage and apparel sales.

U.S. GDP Growth in the First Quarter Will Be Its Typical Disaster Nevertheless, the effect of the recent data reports on U.S. GDP growth in the U.S. will be devastating in the short run. The model at the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow division has GDP growth in the first quarter down to just 0.5%, down from as high as 2.5% in the middle of February. The consensus forecast has dropped from 2.3% at the beginning of the quarter to just 1%. Most of the drop across all of the forecasts has been led by the consumption category that will likely show little or no growth in the first quarter, breaking a long string of quarterly growth driven almost entirely by consumption.

Yes, some of the data flukes will reverse themselves in later quarters. Still, in some years, it has proved more difficult to dig out of the first-quarter hole than many expected. Despite the slow first quarter, we are sticking with our 1.75% to 2.0% forecast for the full year.

The bond market has obviously caught on to slowing growth trends faster than equity markets. Yields on the 10-year U.S. Treasury Bond has dropped from 2.6% in early December to just 2.24% currently despite two Fed rate increases in the interim.

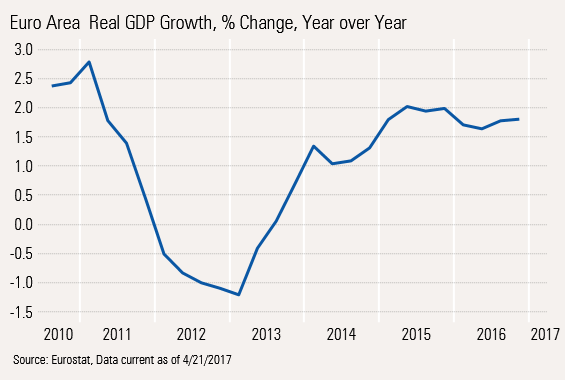

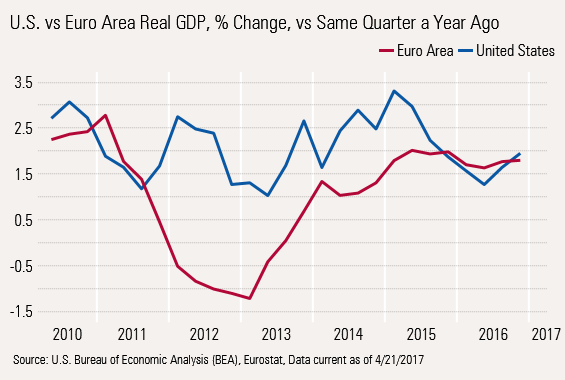

IMF Upgrades European Growth Outlook The International Monetary Fund is now forecasting that euro area will grow at a 1.7% rate in 2017 instead of the 1.6% projected in January. That forecast dipped as low as 1.4% as of July after the June Brexit vote. For such a slow-growing area that has faced increased terrorism, the Brexit vote, and surprising election results, the upgrades since last July are quite remarkable. Based on strong first-quarter results and the Markit Flash Manufacturing PMI report released this week, we believe that the IMF is still too conservative on Europe and too aggressive on the U.S.

The United Kingdom, which is not part of the euro area, has seen its 2017 growth forecast boosted from 1.3% to a surprising 2%. The higher growth outlooks for the euro area and the U.K. are a result of better exports, resulting from a generally weak euro, but also better domestic demand, especially in Spain and Germany, driven by higher wages and better employment growth.

On the export side, improving commodity markets have helped in several ways. First, a lot of capital goods produced in Europe (and Japan and the U.S. for that matter) are used to find, extract, and transport commodities. With improving prices for commodities, interest in production equipment is increasing again. Also, perhaps somewhat perversely, higher prices have broken some of the deflationary mindset and worries about a deflationary death spiral that were a greater concern in Europe than in the U.S. Finally, stronger commodity-oriented economies create demand for other European-produced products and generally support more world trade and growth.

For some time, we have felt that underlying strength was building in Europe but that Europeans themselves were never convinced. Every piece of good news was followed with a caveat that yet another disaster was just around the corner. The European boogeyman of the day has rotated from China’s slowing growth, Brexit, to potential Trump administration trade policies. The IMF has generally been way too optimistic about Chinese and U.S. growth, continuously and embarrassingly, but too pessimistic about Europe. The IMF completely missed the fact that Germany grew faster (1.7%) than the U.S. (1.6%) in 2016. And if they think the U.S. can grow at 2.3% in 2017, they are truly delusional. We would be pleased if the U.S. could even get to 2% growth in 2017. Below is the historical comparison between the U.S. and European GDP growth during this recovery. A wide gap is clearly closing as the dollar has gained and the euro has weakened and U.S. stimulus slowed sooner.

Interestingly the IMF World Forecast, which includes the European forecast, is not exactly a paragon of optimism, either. The report's opening paragraph states the growth forecast and includes four vaguely positive sentences on China, the U.S., and commodity producers. That short paragraph is followed by two much longer paragraphs of worries.

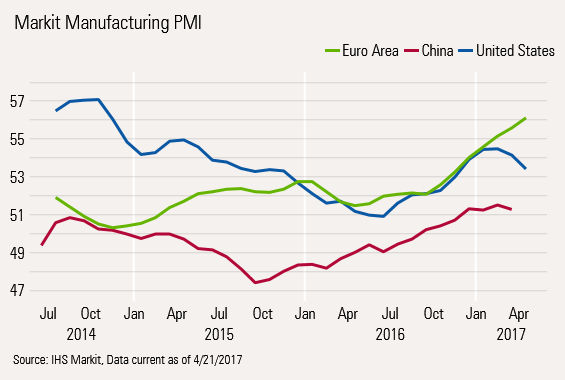

European Manufacturing Continues to Gain Ground The normally skeptical folks at Markit, which a year ago made the IMF seem bullish, have broken out of their shell with decidedly more positive data and commentary that borders on gushing. European purchasing manager data from both the services and especially the manufacturing sector continue to exceed expectations, supporting the IMF's recent GDP upgrade for Europe. The composite flash reading for April increased yet again to 56.7, up from 56.4 and the highest reading in six years. That is not a typo, six years, not six months. The correlations between the composite reading and future GDP growth are decent, if not perfect. The current reading suggest second-quarter GDP growth of 2.8% compared with 2.4% in the first quarter.

Turning to the manufacturing sector, the news is just as good, especially compared with the rest of the world. The April flash reading increased from 56.2 to 56.8, also a six-year high. The results continue to outpace those in the U.S. and China, as shown below.

New order growth, the most forward-looking component, is now at its highest level since March 2011, which should bode well for the months ahead. Exports were a big part of the order improvement as a cheaper euro, the key benefit of loose monetary policies, works its magic after a slow start. We had mentioned that Europeans have been surprisingly skittish, at least until recently. In the face of improving order books, businesses were content to let backlogs build and accept slower deliveries and keep hiring to a minimum. That tide is shifting: The reading for manufacturing employment has now hit its highest since 2000 in April. The positive employment terms in turn have begun to raise internal demand in a region that has been dominated by export activity. The Markit report singled out Germany and Spain for sharply improved internal activity.

We can’t really avoid publishing a portion of the Markit data commentary on the European economies. While they just couldn’t avoid an opening warning about the upcoming French election, the rest of the quote is astounding for its broad-based optimism.

“France’s elections pose the highest near-term risk to the outlook, but in the lead-up to the vote the business mood has clearly been buoyant. Growth in France has risen above that seen in Germany amid rising optimism about the future. Both countries are enjoying their best growth spells for six years, while elsewhere in the region the pace of expansion has accelerated to a near ten-year high, cementing the increasingly broad-based nature of the upturn.” --Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

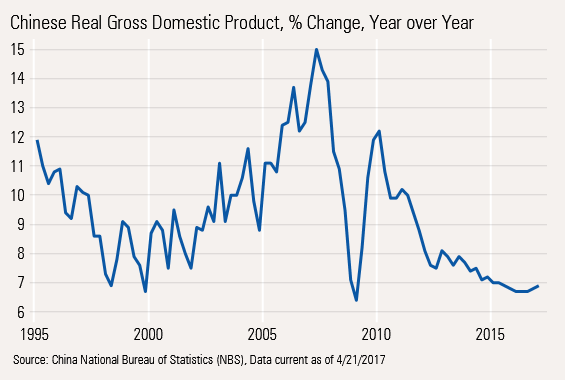

China Does Better Than Expected in 1Q, With Government Help, Strong Real Estate Markets It's hard to believe that it was just a year ago that falling growth rates in China (along with falling commodity prices) were the top issues on investor minds. This spring, the 6.9% Chinese GDP growth rate elicited barely a yawn from world markets. The 6.9% rate exceeded expectations and full-year growth of 6.7% in 2016 and vague government targets of 6.5% or so growth.

Though as usual, the growth levels are regarded skeptically as government infrastructure spending and an unsustainable robust real estate market have kept growth rates from sinking further as many of us feared. Dangerously high private debt levels remain a major concern. Still, without an external shock, surprisingly complacent world markets, and dwindling opportunities elsewhere, investors seem to be giving China a pass for now. We believe the need to pull in overly ambitious real estate speculation and to corral at least some of the debt problem could affect second-half growth.

Looking longer term, even the control-oriented Chinese government will be hard-pressed to offset demographic headwinds to grow GDP at even 5% or 6%. The Chinese one-child policy of the late 20th century and very early 21st will come home to roost within the next decade, compounded by a shortage of females and a plethora of single males.

Monthly Housing Data Volatile, Though Not Much Has Really Changed Housing has been an important contributor to GDP growth during the recovery, though perhaps not nearly as much as in past recoveries. This recovery was unusual, though, since because of inventory overhangs and drastically tighter credit conditions, housing was one of the last GDP components to show improvement. Overall, total housing has added 0.25% to GDP growth on average since 2012, in a range of 0.11% to 0.39%. We suspect based on this week's data that housing will likely be able to very modestly outperform the recovery average. Housing permits, a precursor to new-home sales and starts and existing-home sales both had nice bounces in March. Meanwhile builder sentiment faded modestly but remained at a relatively high level, and starts, which had been running unnaturally above permit data, showed a monthly decline.

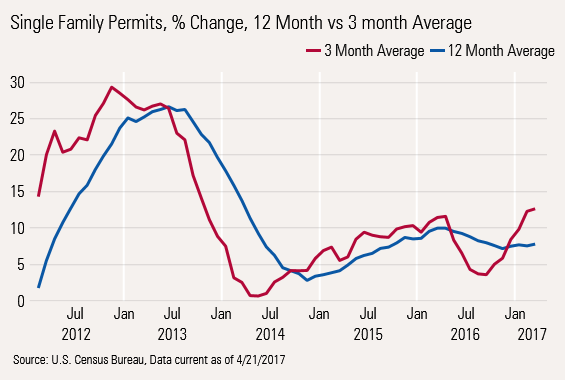

Of the myriad data released this week, single-family permits are probably the most important of the housing indicators. Year-over-year three-month averaged data and rolling 12-month data all moved in the same direction in March at what we view as healthy and sustainable rates consistent with new-home growth of around 10%. However, to be fair, single-family permits, which were unusually strong in February (and revised higher this month) were off a smidge month to month, but nothing to be concerned about.

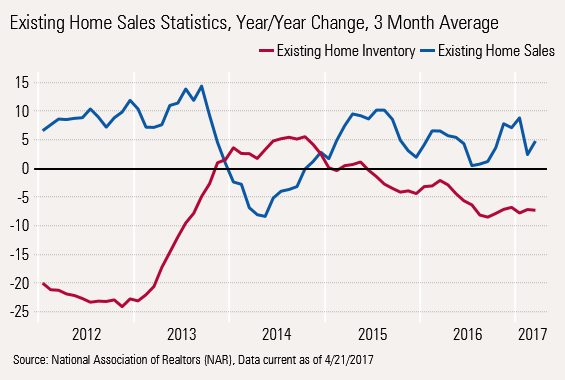

Existing-home sales, which had a rough year in 2016, stabilized early in 2017. The same data indicates that existing-home sales could improve to 5% in 2017 from a meager 3% in 2016. The recent improvements have come despite inventories that still appear to be dangerously low. If we are wrong about 2017 existing-home improvements, that is probably why.

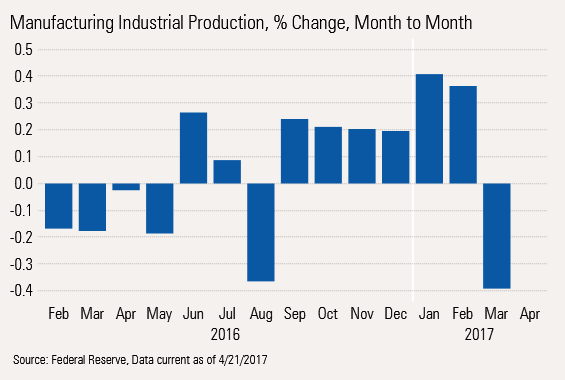

After a Six-Month Run, Industrial Production Suffers a Small Setback After a return to deflation and declining retail sales in March, a falling growth rate for manufacturing-based industrial completed a trifecta of poor results, at least on a month-to-month basis.

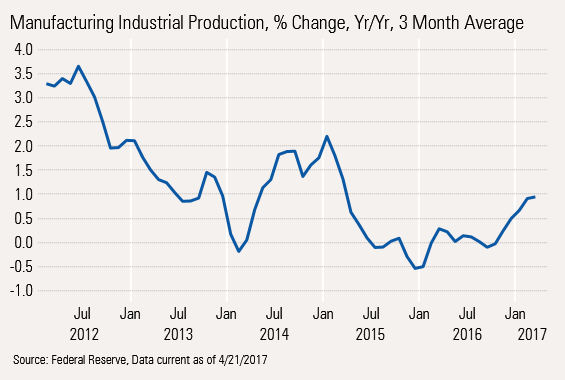

To be sure, we aren’t exiting the first quarter on a high note, and expectations have come back to Earth for the whole economy. Still, like the disappointing retail sales and deflation data revealed last week, the industrial production data released this week looked the same or better than recent trends on our year-over-year averaged methodology. This tends to remove those pesky seasonal factors and dull the impact of weather-related flukes.

The year-over-year averaged industrial production is now over 1% after showing 0.5% for January. The new orders data continues to suggest that industrial production could approach 2% by the end of the year. A stronger world economy that we discussed at the beginning of this week’s column should also be a small positive unless the politicians in Washington manage to do something to slow world trade.

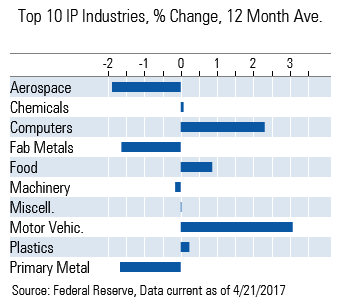

We're also a bit concerned that even on a rolling 12-month basis, strong improvements are highly concentrated in just a handful of categories, including motor vehicles, food, and computers and electronics.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)