Income Annuity Decision: Start Now or Wait Until Later?

Contributor Mark Miller discusses how immediate and deferred income annuities can help investors mitigate longevity risk in retirement.

Fewer workers expect traditional pensions when they retire these days, yet most also are acutely aware that longevity is rising--and that they run the very real risk of running out of money at an advanced age.

These concerns have boosted awareness of the importance of optimizing Social Security and have sparked growth of a relatively small category of annuity sales, the deferred income annuity.

The deferred income annuity is an offspring of the more basic single premium immediate annuity. Both offer ways to purchase guaranteed lifetime payments as a way to bolster retirement security. As their names suggest, the single premium immediate annuity starts payment immediately upon purchase, while the other defers payments to a later date. Deferred income annuities that start income at an advanced age--say, age 80 or 85--intend to provide "longevity insurance."

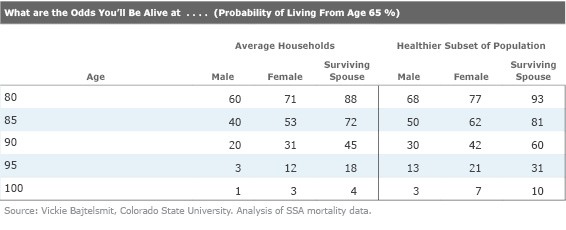

Expected longevity for men and women at age 65 has jumped more than 10% since 2000, according to the Society of Actuaries. Men who reach age 65 can be expected to live to an average age of 86.6, and women to 88.8. But 31% of women who reach age 65 will make it to 90. And for those with better health, the figure rises to 42%.

But which is the more effective hedge against longevity risk--the deferred or single premium immediate annuity? The question crossed my radar following a recent column I penned for The New York Times on longevity risk.

Joe Tomlinson, a financial planner and actuary based in Greenville, Maine, who has done extensive research on retirement planning, created a custom projection for the column illustrating the challenges of managing longevity risk with savings alone. Using Monte Carlo analysis, we illustrated the case of a hypothetical couple with a $1 million nest egg to show that even fairly affluent households run the risk of retirement plan failure due to longevity--with failure defined as a forced, sharp cut in living standards when savings are exhausted.

Filing for Social Security at age 65 and living off savings produced a 47% chance of plan failure, with a $168,000 shortfall in resources. Not good.

Next, we delayed the couple's Social Security filing to age 70. Tomlinson believes delaying Social Security should precede any consideration of an annuity in most cases, because the return on delayed filing--roughly an 8% bump in monthly benefits for every 12 months of delay--offers a payout that no annuity can match.

Delaying to age 70 to claim benefits sharply reduced the risk of plan failure to 38%. Just as important, the corresponding lifetime shortfall was much smaller: $58,000. Then, Tomlinson mixed in a single premium immediate annuity purchase at age 70--that reduced the failure risk to zero.

Single premium immediate annuities and deferred income annuities are both legitimate tools for hedging longevity risk, but Tomlinson prefers the former. He thinks the latter exposes buyers to worrisome amounts of stock market risk while waiting for payments to begin--and he said as much in the New York Times column. That sparked an interesting exchange of views with Matt Carey, chief executive of Abaris Financial, a 3-year-old online startup that sells income annuity products. The company's intent is to use technology to simplify the annuity-buying process, and to wring out expense.

Abaris sells both flavors of income annuities, and Carey, also quoted in the Times column, sees uses for both--although Abaris focuses mainly on deferred income annuities, which require less upfront investment, and specifically target longevity risk.

"If you're 65 and retiring, think of SPIAs as a pension replacement," Carey says. DIAs, on the other hand, offer tail-risk longevity protection. With a SPIA, the biggest drawback is simply that it takes a large amount of assets to get meaningful income, he adds.

"I haven't had many clients buy a SPIA to cover all their fixed expenses unless it has represented less than 30% of their portfolio," he says.

"The reality of today's interest rate environment is that getting $50,000 in pre-tax income for a 65-year-old male requires $725,000," Carey says. "And unless the client's sole goal is not running out of money, it's difficult to justify that allocation unless the individual has at least $2 million, based on some of the Monte Carlo work I've seen."

Tomlinson counters that the single premium immediate annuity investment doesn't have to be large--at least not as a percent of total assets.

"I find that after delaying Social Security, it is feasible to cover basic living expenses without a huge SPIA purchase," he says.

Indeed, in the projection we worked up together, the couple spends $298,000 on a single premium immediate annuity at age 70--less than 30% of the original $1 million portfolio--and they still have $416,000 remaining liquidity.

Income annuities have been getting more attention lately as a growing number of retirement researchers--and consumers--train their attention on the problem of longevity risk. At the same time, the U.S. Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule has put pressure on other guaranteed income products like variable annuities, which usually are more complex and expensive. (This topic gets a full airing in Morningstar’s recent Retirement Readiness Bootcamp on how to maximize guaranteed income in retirement.)

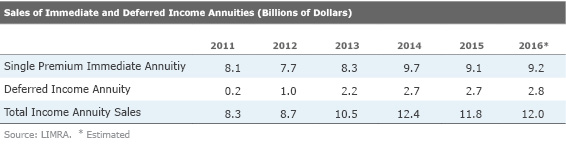

But income annuities still represent a very small part of the overall retirement market. Sales in 2016 for immediate and deferred annuities totaled an estimated $12 billion, according to LIMRA, the industry consulting and research firm.

DIA sales have been rising briskly for the past five years, but the overall income annuity market pales in comparison with the $7.3 trillion held in IRAs at year-end 2015, and $6.7 trillion in workplace-defined contribution plans, according to the Investment Company Institute.

DIAs have been around since the mid-1990s, but only began gaining traction in 2012, when insurance companies began to market them as a way to build your own pension, says Judy Zaiken, corporate vice president and research director at the LIMRA Secure Retirement Institute.

Indeed, just 25% of today's workers expect a traditional pension will be a major source in retirement income, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute’s latest Retirement Confidence Survey.

Recent LIMRA research on DIAs and SPIAs shows that DIAs attract younger buyers--the average DIA purchase age is 59, compared with 72 for SPIAs.

DIAs received a boost from the Obama administration in 2014, when it approved rules for offering qualified longevity annuity contracts within 401(k)s and IRAs. QLACs ease the path to DIA purchases in tax-qualified accounts by excluding their value from required minimum distribution requirements. The idea here is to buy a QLAC near or at retirement, with payments starting only if the buyer reaches an advanced age, say 80 or 85. Hence, they are intended to be longevity insurance.

But most DIA buyers aren't using them that way. LIMRA found that the average DIA buyer start taking income at a relatively young age--between 65 and 70. Just 3% of buyers defer income to a date late enough to be considered longevity insurance, says Zaiken, and the average deferral period is just 7.7 years.

"It's a very efficient way to buy, since few people will actually make a claim--but the idea of buying something now to protect yourself 30 years down the road is a tough proposition," she says.

EBRI data backs that up. Among current workers, just 7% say they would be very interested in buying a longevity annuity, with 38% saying they are somewhat interested. Meanwhile, 52% are not too interested in the idea, or not interested at all.

The income start data backs up one of Carey's key points--namely, that starting relatively young to build a pension at retirement age can be a very attractive option.

"There’s no inherent reason why the decision to buy retirement income shouldn't be spread out over time, with some of it happening before retirement," he says.

Tomlinson acknowledges that much of the recent buzz has been around DIAs -- partly due to the rollout of QLACs, partly due to the build your own pension marketing push from insurers, and partly due to the attractiveness of lower upfront investment.

Still, he sees several reasons to prefer a SPIA. First, it's difficult to predict exactly when you'll retire, so SPIAs are more flexible. Second, the SPIA strategy allows more focus on pre-retirement savings accumulation. Finally, his analysis suggests that SPIAs lead to a higher payout than a DIA structured as longevity insurance. In an article last year for Advisor Perspectives, he compared a SPIA purchase at age 65 with a QLAC purchase at the same age that begins paying level income at 85. For the latter, the QLAC is paired with a bond ladder for the 20-year deferral period as a stand-in for the returns that insurance companies might generate on the DIA premiums paid.

The SPIA (with no refund feature) provided a 6.18% payout rate, compared with just 5.05% for the QLAC.

A QLAC seems to provide greater liquidity during the years of waiting for DIA income to begin, by retaining a larger investment portfolio. But some experts question that assertion. An excellent post at Oblivious Investor notes research finding that the portfolio is not really available to be spent any way you like; the liquidity is partially illusory, since assets must be matched to liabilities--in this case, the liability is living expense.

Tomlinson agrees.

"The liquidity is not necessarily real, if this is money you will need to pay for food and housing, or to pay to repair a roof if it start leaking," he says. "It is phony liquidity, because you might have to liquidate the ladder, or part of it."

Mark Miller is a retirement columnist and author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work, and Living. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)