Economy Not as Strong as Consensus Believes

Even with a possible stimulus package, we think the economy will be hard-pressed to grow much more than 1.5% to 2.0% in 2017.

Markets this week seemed particularly confident that better economic news was just around the corner. Despite a lack of many definitive proposals, markets seemed sure that the combination of tax cuts and increased infrastructure spending is a done deal. This week, there was new hope that the regulatory burdens that so many businesses had complained about would be greatly diminished. This new optimism was based on the appointment of more antiregulation proponents, including Andrew Puzder, a minimum-wage increase opponent, to Labor; and Scott Pruitt, a critic of environmental laws, to the EPA.

We don't know if there was a direct cause and effect, but U.S. markets seemed excited about the news. Most major equity markets, even including emerging markets, moved ahead at about a 3% clip since last Friday's close, at least in U.S. dollar terms. However, going by Election Day, the U.S. is the standout performer with the S&P 500 up almost 6%. European markets expanded just about 2%, although much of that underperformance is due to an increase in the dollar. Emerging markets are bringing up the rear since Election Day, losing about 3%. That gap was wider, but better import-export data out of China this week brought even emerging markets back to life.

Speaking of rising from the dead, commodities are up about 6% since the election, though little-changed this week because of the recent oil producer agreement to cut production as well as the use of more basic materials in infrastructure rebuilding. Another winter vortex, predicted to hit the Midwest, could continue to fuel the energy rally.

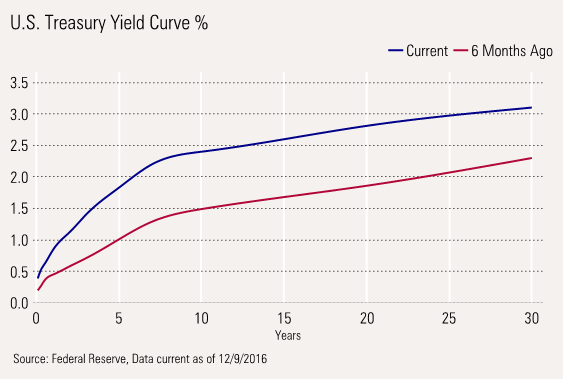

Interest rates continued to move higher (and bond prices lower) this week with the U.S. 10-year bond now yielding 2.47% versus 1.86% on Election Day and 2.39% a week ago. This week, the European Central Bank announced it would continue to buy bonds through the end of 2017 instead of the previous expiration date of March 2017. That announcement was widely anticipated. Surprisingly, it also announced that its bond purchases after April would be smaller by about $21 billion per month. That caused interest rates around the world, including in the U.S., to tick up after the midweek announcement.

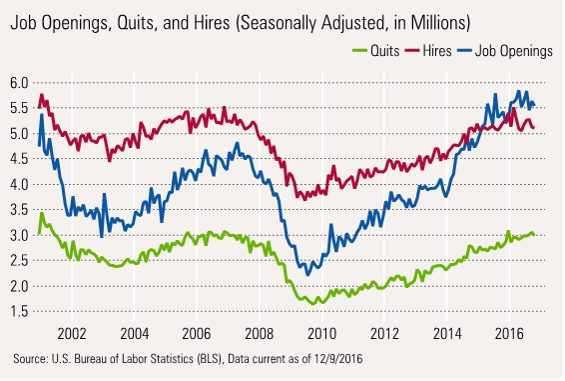

There wasn't much economic data out of the U.S. this week. The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey continued to indicate difficulties in hiring workers. There just doesn't appear to be enough supply. Given the almost nonexistent growth in the working-age population, that result isn't surprising.

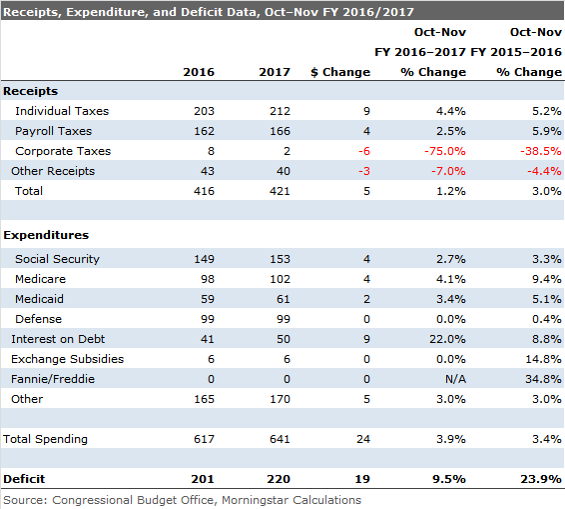

In other news, after a month of improvement, the federal budget report for November suggested that the budget deficit was getting worse again. Tax collections remained atrocious, with almost no growth compared with a year ago, even as expenses moved higher. Higher interest payments due to higher inflation rates also appeared to be a growing problem. Trade data, even before the election of Trump, also moved into the worry column with recently released October data. While imports and exports have been moving down in tandem for some time, October imports spiked higher as exports continued to fade. That drop in exports became a little clearer in October as soybean exports fell back to earth.

Despite Contradictory Economic Data, Market Confident of Rate Increase Next Week As I mentioned in my introduction, interest rates are already up sharply since the election on a combination of apparently stronger fundamentals, inflation fears, and Fed expectations. Ultimately, markets and the economy moved rates higher even before the Fed acted. We noted that the 10-year bond yield is up 0.6% since Election Day and 1.1% above its post-Brexit low, though most forecasters believe the Fed will raise rates only by 0.25% (on the shorter-term Fed Funds rate). A recent Wall Street Journal survey of economists shows expectations are currently for three additional hikes in 2017, potentially bringing the Fed Funds rate to 1.3%. Those expectations have moved rates higher across all maturities, as shown in the yield curve below.

We Don't Believe the Economy Is as Strong as Some Believe, and Not as Strong as Consensus The current reading on the economy seems to be that after a slump over the winter months and renewed slowing in August, the economy has shown a generally stronger pattern of growth. With stock market-related wealth gains, potential stimulus, and now regulatory relief, even more gain lies just around the bend. That narrative for 2016 has led to some optimistic forecasts for 2017 despite what will surely be a poor 2016.

Full year-over-year GDP growth for 2016 is likely to fall to 1.6%, based on weakness early in the year (with three quarters of the year already done and relatively strong consensus on the fourth quarter, there isn't a lot of room to argue with that forecast).

That result compares with 2.6% in 2015 and has generally averaged 2.0%-2.5% annually during the current recovery. The Wall Street Journal Economics Survey showed expectations of 2.6% GDP growth for 2016 last December. The December forecasts have proved to be too optimistic for most years of the recovery. Continuing with that optimistic bent, those same forecasters are expecting 2.4% growth in 2017.

That seems too optimistic to us given slowing employment gains, which will bring in total wages and consumption. Headline inflation will likely be higher, too, given rising energy prices, also constraining consumers. Government spending has been going nowhere fast as increased pension payments limit state and local governments' ability to raise spending in other categories that more directly and immediately benefit the economy. However, Trump stimulus programs could be the saving grace for the government category.

Export data was already looking poor and a stronger dollar and trade restrictions would likely make it difficult to increase exports much at all. Business spending has been awful for most of 2016 but may have the potential for improvement next year as labor shortages grow and force businesses into investing in more labor-saving devices. Given these factors, even with a limited stimulus package at midyear, we think the economy will be hard-pressed to grow much more than 1.5%-2.0% in 2017.

Furthermore, we aren’t believers in the current narrative of what has happened to the economy over the past year and a half. We don't think the underlying tenor has changed much, with demographics slowly pulling economic growth lower from this recovery's norm of 2.0%-2.5% toward 1.5%-2.0%. (Slower population growth means fewer people to buy things, and older populations tend to consume less.)

The apparent rebound since August is due to the fact that August data was sharply reduced by storms in the South and some statistical artifacts due to calendar selling day counts. Almost every major economic indicator looked terrible in August: Industrial production was down 0.1%, employment growth dipped in August after strong growth in July, personal income barely grew at all, as did retail sales excluding autos and gasoline. There wasn't any particular news that would seem to be the cause, other than the weather and statistical issues. That unnatural low point in August caused September and October to look suspiciously good on a month-to-month basis.

Year-over-year, averaged growth data paints exactly the opposite picture on these four key metrics. Retail sales (excluding autos and gasoline), industrial production, employment, and real disposable personal income all seemed to be growing considerably slower than a year ago. And given the strength at the very end of 2015, these year-over-year numbers will likely worsen over the next couple of months. Even though this is our favorite way to look at data, we think this paints too bleak a picture of the economy.

We still haven't entirely gotten our arms around why the late 2015 data was so strong (though some mixture of mild weather helping construction, use-it-or-lose-it budgeting at large companies, plunging gasoline prices, and just plain weird auto data were probably at work). Private-sector job growth averaged close to 300,000 jobs in the fourth quarter (and growth was considerably higher before some major revisions). That set up the fourth quarter to be a nearly impossible comparison to improve on, perhaps making the normally dependable year-over-year data less so.

So as much as a rough August set us up for a bunch of good-looking month-to-month improvements, the strong 2015 fourth quarter set us up for dismal year-over-year comparisons. The month-to-month data growth will likely mellow out from its apparent rebound. Then, the year-over-year data should show some improvement early next year when the data is compared with a relatively weak first-quarter 2016. So the truth likely lies between these two data sets: no boom that the market is proclaiming, and no bust that we thought a real possibility just a few short months ago.

Negative Impact of Trump Measures Could Hit Economy Before Stimulus Plans Hit; Policy Changes Always Take Longer Than Expected The market seems to have really latched on to the benefits of a new administration. These are potentially real, but as we learned in 2009, new policies, even with one party in control, take longer to implement than one expects. Things tend to get watered down, and shovel-ready projects still can take years to even start. Tax cuts can help sooner, but likely won't greatly benefit those on the bottom of the income curve who pay no federal income tax (they do pay Social Security as well as state and local taxes). Those people at the lower parts of the income curve are more likely to spend those tax cuts quickly.

Higher Rates Could Hurt the Housing Market in a Hurry So until any of Trump's policies get implemented, the economy is likely to face considerable pressure. The first real worry point is housing getting hit from higher interest rates. Those higher 10-year bond rates we spoke of earlier are the primary determinant of mortgage rates, which are already sharply higher. And with prices almost 6% above year-ago levels, affordability will become a real issue. We had thought there might be a surge in housing activity in an attempt to beat higher interest rates, however, mortgage applications have been down three of the past four weeks.

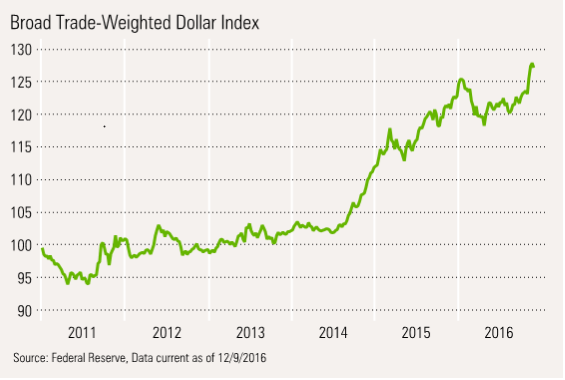

We also worry about trade. The dollar is now stronger, so exports may be harder to come by. Lower prices, also the result of a stronger dollar, should push imports higher in the months ahead. The dollar is 4%-5% higher than just a couple of months ago.

Trade Deficit Was Already Worsening Before Trump and Dollar's Renewed Strength Even before the last surge in the dollar, the October trade gap widened from $36 billion in September to $42 billion in October. That likely means that net exports in the fourth quarter will be a subtraction from the GDP calculation. Strength in soybean exports had masked some of the underlying export weakness over the summer months. We suspect that trade will be a subtraction from GDP for all of 2017.

Federal Budget Deficit Was Also Worsening Without Any Help From Trump The November budget report revealed a worsening deficit. The root cause of the problem appears to be related to higher interest rates and major tax collection issues, not accelerating spending. Combined October and November data showed tax receipts that were up just 1%, and were down year over year for the month of November. Lower corporate tax receipts and lower income tax collections from nonpayroll-related income have combined to keep a lid on receipts. This is not a busy time of year for corporate taxes, however. December (a huge collection month) data could provider a clearer picture of corporate taxes. Retroactive adjustment, new tax laws, and lower profits have all weighed on collections. However, the relative importance of each cause and the ability to rebound from current levels are unclear.

The good news is that other than interest expenses, which are up a lot, expense growth--even Medicare and Medicaid--has moderated.

JOLTS Report Suggests Labor Shortage, Making Stimulus Less Effective Given demographics, a shrinking labor pool, and the current low unemployment rate, it might be hard to stimulate growth with more spending. It might just bring more inflation if there aren't enough workers. A large number of job openings suggests that businesses are indeed having a hard time finding workers. The number of openings was modestly lower in the just-released October data, but not down nearly as much as hiring was. Quits, which show worker confidence in the job market, remain elevated.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)