The Squeeze on Active U.S. Stock Funds

Progress has not been their friend.

Sweating the Details One of the first things I learned as a fledgling mutual fund analyst, during Daddy George H. W. Bush's presidency, was the importance of security analysis. The top stock funds, by and large, hadn't timed the market, or wagered on sectors. They had built their portfolios one company at a time, using insights from their organization's research analysts, a professional's eye for accounting statements and, yes, the occasional hints from corporate managements. (Disclosure requirements were looser back in the day.)

Admittedly, not every fund company paid such attention to detail. Some did not wish to assemble costly research staffs, while others were unable--or unwilling--to create the type of corporate culture that is required to recruit and retain the top fund managers. (Hint: Don’t send them on marketing tours.) Those companies invested instead on commodity Wall Street research, supplemented by their internal managers’ beliefs. That combination was insufficient. On average, funds from such organizations fared no better before expenses than proverbial monkeys tossing proverbial darts--and worse after their costs were paid.

However, those fund companies that were willing to bankroll the necessary research teams, and that attracted the elite portfolio-manager talent, stood a good chance of enjoying persistent success. Yes, the financial markets were becoming more efficient as they became more professionalized, but there remained openings for well-equipped fund managers who were skilled at reading clues. The door was closing, but it was not yet shut.

It appears to be almost latched today, for diversified U.S. stock funds. (Next Tuesday’s column will consider bond funds and foreign stock funds.)

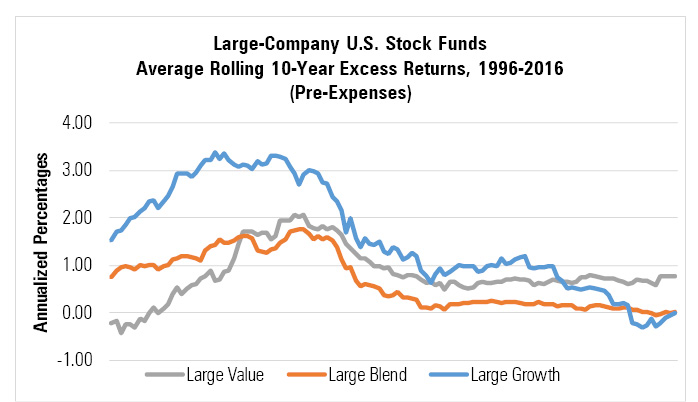

By the Numbers First, large-company U.S. stock funds. Morningstar's Jeff Ptak (thanks, Jeff!) calculated the average excess return over rolling 10-year periods for all surviving funds in the three large-cap categories. The first rolling period, shown at the chart's far left, began in November 1996 and ended in October 2006, while the final rolling period, shown at the far right, started in November 2006 and ended this past October.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

(Technical note: The calculation uses only a fund’s oldest share class, with the expense ratio added back. It then subtracts the performance of the category’s Morningstar-assigned index. The result is the fund’s gross excess returns, as compared against those of a style-specific benchmark. That is, the measurement reveals the top line of what portfolio managers achieved, rather than the bottom line of what shareholders received. Finally, the individual-fund results are summed to form a category average.)

The story is the same for all three categories. The indexes had fared relatively well during the late 1990s because blue chips led the stock market, and the indexes normally carry higher weightings in the biggest companies than do mutual funds. Then, the relative performances reversed course, with the funds beating the indexes from 2000-02 when those blue chips plunged. This pattern appears on the chart, with the funds climbing as the 1990s roll off the 10-year periods, and then sinking as 2000-02 disappears.

The funds’ rise and fall occurred because of a systematic difference between the funds and their benchmarks. (We’ll see other systematic differences on Tuesday.) That is, it was a cyclical effect. Unfortunately for active portfolio managers, when this cyclical effect subsided, it appears to have been replaced by a steadier, and more depressing structural effect: the disappearance of the opportunity set.

The chart’s takeaways:

- Until recent years, most U.S. large-company stock funds beat the indexes, before expenses. From the beginning of the chart (the 10-year period that ran from 1996 through 2006) through its middle, the three lines averaged one percentage point at worst, and above two points at best.

- However, once the New Era crash disappeared from the record, the bulge shrunk. It's now modestly positive for large-value funds and nonexistent for the other two categories. Matching the indexes before expenses means trailing them after expenses. Worse, the trend shows no hint of changing. The orange indicator for large-blend funds, one might say, has flat-lined.

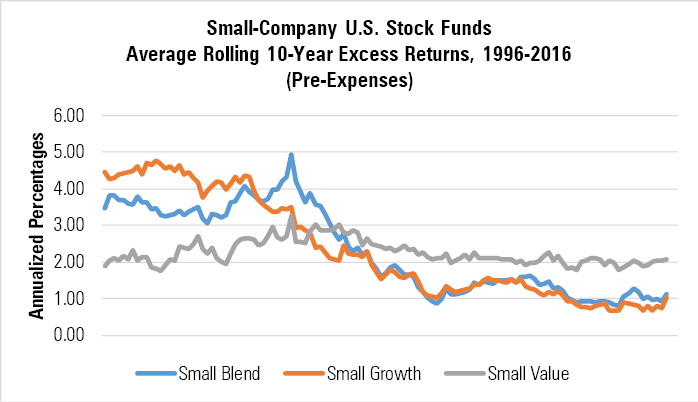

From Big to Small The picture is somewhat better for U.S. small-company funds, but far from encouraging.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

Unlike domestic large-company funds, small-company stock funds have retained an advantage over the relevant indexes. (At least, the indexes that Morningstar has selected to be category benchmarks; substitute a different set of indexes and the numbers will bounce around, although the overall pattern will persist.) However, their victory margin has slid, from an initial average of more than 300 basis points per year, to about 140 basis points today. (Again, as those figures are before expenses, the funds are barely ahead of the benchmark after costs.)

It is often said that because the large-company stock marketplace is more efficient than that of small companies, that it makes more sense to index blue chips than it does secondary stocks. The second chart does support that claim. However, the news is far from encouraging for active small-company funds. Broadly speaking, they appear to be following on the heels of large-company funds, only a decade or two behind. Their door is also closing.

Wrapping Up The counterargument to this column is that averages are beside the point. What matters are the best of today's funds. Conceivably, they could be as strong as the past's winners. Who can tell from looking at simple averages?

Fair enough. Except that I have examined the outliers, and they are a ghost of what they once were. In addition, having spent several thousand hours talking to stock-fund managers over the past 30 years, I have a pretty good sense of how this business has changed. And change it has. Details that were once known by few are now known by many. Progress has occurred. And while this progress represents good news for how accurately stocks are valued, it is decidedly less positive for those professionals who are paid to find mistakes in those values.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)