What History Tells Us About the Impact of a Fed Rate Hike

The bond market doesn't respond the same way to every Federal Reserve decision to raise interest rates.

With the presidential election dominating the news, speculation about the possibility of a near-term Federal Reserve interest-rate hike has faded into the background. That's not entirely surprising given that expectations after the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting--at which rates were left unchanged--were that the Fed would likely not move until at least Dec. 14, if it were to move at all.

On Oct. 28, though, 30-day federal funds futures prices, which are widely used as a barometer for market expectations, set the probability of a December meeting hike at a notably high 74%. Even taking into account the many ultimately false signals prior to meetings in the past few years, that's a pretty high number.

That again raises the question of what one should expect if and when short-term rates are raised. Since the credit crisis, the Fed has overseen a period of extraordinary monetary policy: Even with the Fed's December 2015 rate hike, it has kept the federal-funds rate at close to zero for an unprecedented nearly eight years. (Short-term market rates, heavily influenced by the Fed, have been at rock-bottom levels for most of that period, though they've been climbing sharply all year, partly in anticipation of supply issues surrounding shifts in demand from money market funds.)

But that's just short-term rates. What will a Fed rate hike mean for the broader bond markets? The answer is that it depends. The bond market doesn't respond the same way to every stretch of rate hikes. Whether investors believe the Fed is acting too quickly, too slowly, or perhaps not enough can make all the difference.

Source: Morningstar.

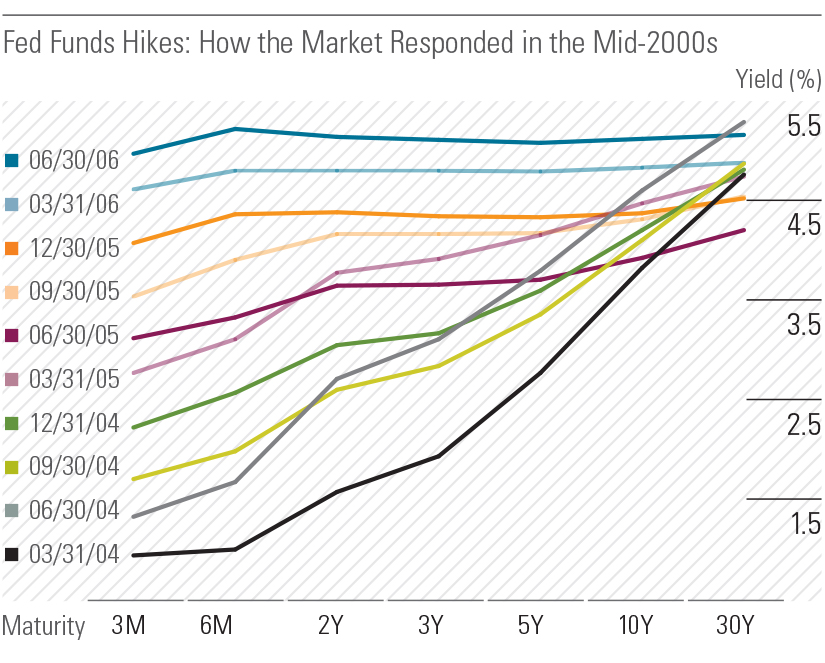

That's the message of the accompanying charts, one from a period of Fed rate hikes in the 2000s and another from the mid-1990s. During the former, the Fed raised short-term rates roughly 4 percentage points between March 2004 and June 2006. Compared with some earlier cycles, the reaction was measured. Although their longer maturities meant they didn't escape volatility, yields for 10- and 30-year Treasuries didn't rise anywhere near as much as the federal-funds rate did (as the first chart shows, leading to a "flatter" yield curve). Prices fell for bonds in both tenors, but factoring in interest, the 10-year bond lost 1.7% for that period, while the 30-year bond actually gained 2.2%. The (then) Lehman Brothers Aggregate Bond Index rose 3.4%.

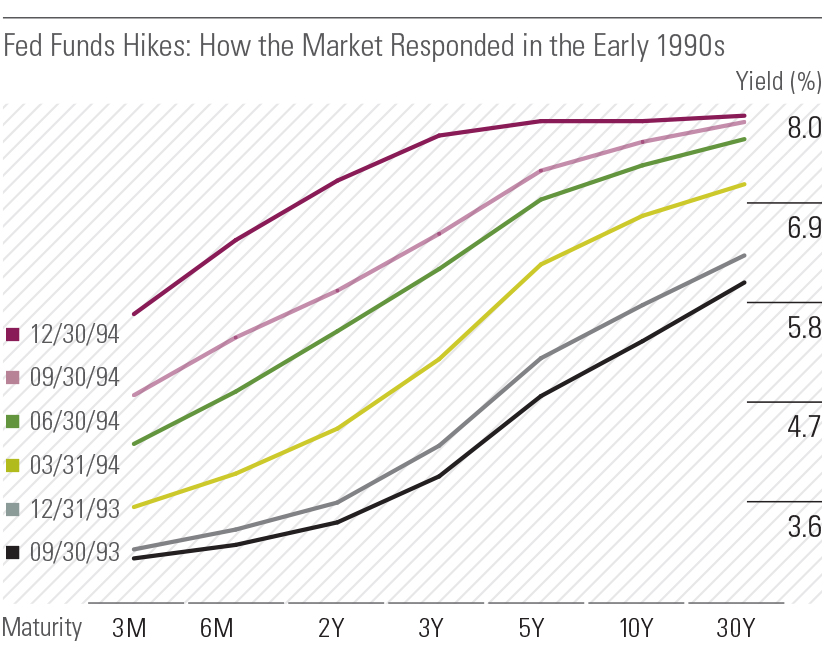

But things can get much worse. Rate cycles rarely occur with the same speed, magnitude, or length. When the Fed hiked rates rapidly in 1994, for example, investors pushed longer-term bond yields up in much tighter step with the Fed's short-term rate hikes, and long-maturity bonds were shellacked. (The second chart shows short and long-term rates nearly moving in tandem, a so-called parallel shift in the yield curve.) That environment was chock-full of other events that spooked the market. However, the fact that the Fed moved so far and so quickly in pushing up short-term rates helped trigger panic among investors. Then-Chairman Alan Greenspan later said in a 2013 Bloomberg article, "You construct what we used to call Fed-speak. Nobody was quite sure I wasn't saying something profound when I wasn't." The 10-year Treasury lost 7.9% in 1994, while the 30-year bond slid more than 12%. The broader Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index slumped 2.9%.

Source: Morningstar.

In addition to the questions about how fast the Fed will hike rates and whether the market thinks the Fed is moving too quickly or not quickly enough, today there are a number of other factors at play. These include a relatively weak global economic outlook and strong overseas demand for long-term Treasuries. That makes it extra tricky to predict how funds will fare when the Fed chooses to act.

Here are some observations about the potential impact on non-Treasury sectors:

- Some rate shifts, such as those of 1994, can be especially damaging to long-duration funds: The long-term bond Morningstar Category tumbled 6.80% that year. Its results during the March 2004-June 2006 stretch were much better (0.76%), but both showings left the category near the very bottom of the fund universe.

- The flip side is that even though short-term rates are the most directly affected by the Fed, short-duration funds almost always perform better than others during rising-rate environments. However, the impact can still vary from one rate cycle to another, especially depending on how fast the Fed chooses to move.

- If the economy is healthy or gaining strength, you can usually expect credit-sensitive funds to perform better than higher-quality, longer-maturity fare. However, that may not prove true in all markets; if bond yields increase significantly, so too will borrowing costs for corporate issuers, which could eventually put pressure on their financial health.

- Normally the last two items make bank-loan funds--which hold junky floating-rate loans--star players. The wild card this time is that, to attract investors during rock-bottom rate environments, many loans have promised a minimum level of income regardless of how low short-term rates have been. That floor has commonly been set at a three-month Libor rate of 1%, so that metric's 0.88% level as of Oct. 28 helps, but if it doesn't get over a loan's floor, a move by the Fed won't translate into an immediate change in a loan's payouts.

A version of this article was published in September 2015.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)