Being Like Buffett: Easy to Say, Hard to Do

There are no public investment funds that are managed as patiently as were Berkshire Hathaway’s early portfolios.

Pale Shadows

Every investment manager admires Warren Buffett. Yes,

Of course, while every manager desires Buffett’s results, most do not mimic his investment approach. Concentrated, low-turnover portfolios are not for everybody. There are, however, two dozen U.S. stock mutual funds that could reasonably be called Berkshire Hathaway hopefuls. They have large-value or large-blend investment styles, fewer than 25 stock positions, and annual turnover of less than 50%.

Their collective results stink. The logic sounds good. Having portfolio managers use their research to best effect by investing only in their favorite ideas, then limiting the fund's trading costs by holding those securities for the long haul, would seem to make sense. But things do not play out that way.

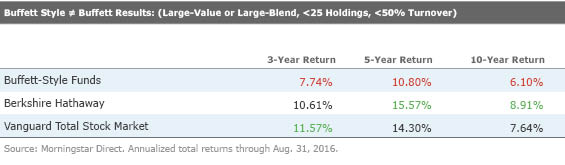

Here are the most recent numbers, through Aug. 31, 2016.

That’s awful--not merely disappointing, not merely bad, but terrible. Of those 25 Buffett-hopefuls, two have beaten

An Explanation In an inaugural blog, John Hempton of Bronte Capital attempts to explain the problem. If you wish to be the next Warren Buffett, argues Hempton, then you really need to act like Warren Buffett. And that means extreme patience. Writes Hempton:

Buffett has often said, "I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only twenty slots in it so that you had twenty punches--representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you'd punched through the card, you couldn't make any more investments at all. Under those rules, you'd really think carefully about what you did, and you'd be forced to load up on what you really thought about. So you'd do so much better."

The imitators, states Hempton, fail because they don’t “even come close” to that level of inaction. “Several big-name so-called Buffett acolytes have made more than three to five large investments in the last three years, and at prices that can’t possibly meet the twenty punch-card test. Most phony Buffett acolytes have been turning stock over faster than that.” Every manager who invokes Warren Buffett is fibbing--“Every last one of them.”

(Except for those who run Voya Corporate Leaders Trust LEXCX, which since time immemorial--OK, 1935--has held the same 20-something companies, aside from adjustments caused by corporate actions. Had you invested $10,000 in that fund on Pearl Harbor Day, reinvested all distributions, and escaped the IRS, you’d have $18 million today. Admittedly, you’d be getting on in years, but very very wealthy.)

Hempton’s comments spare neither himself--“somewhere along the line I realized I was a phony too”--nor Warren Buffett’s successors at Berkshire Hathaway. “Todd Combs and Ted Weschler have turned over many stocks in the past few years--and at prices that don’t reconcile with any twenty-punch-card philosophy. They are phonies, too. Just a little less egregious than many other Buffett acoloytes.”

Impediments to Success "Phony" might be harsh, but the claim is correct. There are no public investment funds that are managed as patiently as were Berkshire Hathaway's early portfolios.

For one thing, the approach doesn’t suit the mutual fund format. Those starting such a fund would either need to invest in many of those 20 ideas at once, or hold mostly cash for many years while gradually building up the stock positions. The first would flunk the investment test, and the second could not be marketed. (The only practical way to implement the 20-card tactic would be to begin with a fully invested index fund, then periodically replace 5% of the portfolio with an actively selected stock.)

Also, states Hempton, it's so very hard to do so little. As with the rest of humanity, investment managers want to act, particularly when returns have been weak and their funds are lagging. Standing pat when under duress feels unnatural and looks appalling to customers. He writes:

Good luck with that!

Investment Lessons As a professional investment manager, Hempton has responded to the impossibility of being a true Buffett disciple by breaking from the ranks. He not only holds more stocks than he believes is optimal, but he also puts some of his cash to work by shorting securities. Such tactics make sense for somebody who is paid to invest and has customers who demand explanations. It's too difficult to be pure.

However, it should not be difficult for us, the investors. We are not paid to invest--in fact, we pay for that privilege, through trading and transaction costs. We do not need to justify our inactivity. We have no customers who threaten to leave. We can take our time, resist the temptation to trade, and take action only when truly outstanding opportunities arise.

And we can avoid buying the funds of Buffett hopefuls, unless one of those funds is a rare, happy exception. Investors tend to think of fund managers as having advantages--training, resources, smarts--that they lack. (This column’s readers probably won’t concede on smarts.) That is often the case. But with emulating Warren Buffett, the opposite is true. The investors have the drop on the professionals.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)