AllianceBernstein, Karl Marx, and Index Investing

A colorful mix, but not very informative.

I Clicked This Headline and You Won't Believe What Happened Next Once, Wall Street research didn't need to shout. Once, investors believed in active money management and the sagacity of brokerage-firm insights. Abby Joseph Cohen penned reports with bland titles like "Low Dividend Yield Not Worrisome" or "Charging Ahead," and they were passed around by institutional investors as eagerly as fifth graders will share captured love notes.

How things have changed. To receive attention for its latest missive on "Fund Management Strategy," Bernstein Research, AllianceBernstein's brokerage arm, chose the remarkable headline, "The Silent Road to Serfdom: Why Passive Investing Is Worse Than Marxism." The company's sensationalism worked, as Bloomberg, Barron's, and CNBC, among others, immediately covered the report. This columnist is also willing to play.

My initial thought was pot, meet kettle. The larger AllianceBernstein manages pools of assets, including mutual funds. Those funds are collectivist endeavors, constructed for the benefit of the group. Some, by using redemption fees, will even go so far as to penalize unwanted individual behavior for harming the general good. So, who is AllianceBernstein to disparage Karl Marx? As a mutual fund company, it should erect the man's statue in its corporate reception.

The second thought also involved pots and kettles, because who am I to complain about catchy, sensationalized headlines? Plus, the Marx allusion can be defended. The paper discusses the process of capital allocation, and Marxism is, after all, one way to allocate capital.

Well played, AllianceBernstein.

Aiming High Of the paper itself, I am less envious. It certainly is ambitious. Topics include

- Marxist principles of social planning;

- Correlations of global stock prices;

- An 18-page analysis of the economics of mining companies;

- Funding shortfalls in defined-benefit plans;

- The role of fiduciaries;

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing;

- The average holding period for mutual fund shareholders.

The authors' inventiveness extends to their citations; in one passage, they quote Marx, then the Old Testament (Genesis), then the Etymologies of St. Isidore of Seville. (Sadly, they neglected Milton, who inspired a genius yet to be born.)

What this all means, I have no idea.

I am not being flip--I do not understand how the vast majority of the paper is intended to support its primary claim, which is that the growth of passive investing, through index funds, harms society by reducing the effectiveness with which capital is allocated to companies.

Simple in Theory To be sure, the paper's basic premise is correct. If every stock shareholder were passive, so that every penny invested into equities came not after assessing that company's relative worth, but instead from copying what the indexes have done, then capital allocation would indeed be flawed. Companies that subsequently grew their revenues and profits would not be rewarded for their successes, and those that shrunk them would not be punished for their failures.

I am willing to believe that such a method of capital allocation would be worse than that achieved through Marxism. (My wife's relatives, having lived in the former Soviet Union, might disagree.) However, such is not currently the case. Far, far from it. Globally, active investors hold two thirds of the world's equity shares, equal to about $45 trillion. That is a large number indeed.

Because global stock markets are so vast, the percentage of assets that is invested passively can expand greatly yet still leave a huge active pool. If 90% of the world's stocks became owned by index funds--an event that will not occur in my lifetime--there would still remain $7 trillion invested actively. That would seem to be enough money to conduct the task of valuing the world's businesses.

Messy in Practice That, of course, is merely a guess. It is possible that I am wrong. It is possible that if and when indexes control 90% of the worth of publicly traded stocks, market prices will become markedly less efficient than they are today. It is possible that although intelligent, informed investors would logically exploit such inefficiencies, that their efforts would somehow be insufficient to make stock prices fully rational. These things could all be true.

But who knows? The authors wave their arms vigorously, but they, too, cannot supply the numbers. Nothing in the paper attempts to identity the turning point. The closest thing is an estimate of the effect that further growth in passive investing will have on the correlations of price movements between stocks. However, correlations are not measures of stock-market efficiency. Nor do they measure the effectiveness of capital allocation.

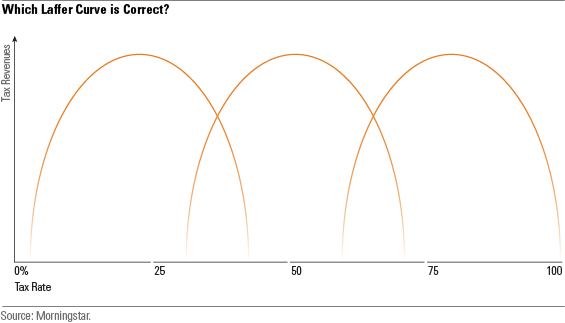

Which Curve? This discussion brings to mind debates about the Laffer Curve. The existence of the curve could not be denied. A tax rate of 0% does indeed yield zero tax revenues. A tax rate of 100%, assuming that the states do not confiscate, yields something close to zero tax revenues. Both extremes are poor. The best taxation policy lies somewhere in between.

The problem with using the curve, in real life, is that its lessons are only applicable if one knows where the curve should be drawn. If not, then changing tax policy might just as easily send a country down the wrong side of the curve rather than up the right side. The Laffer Curve exists. But where can it be located? That question has not been answered satisfactorily--a problem that has complicated the use of the concept.

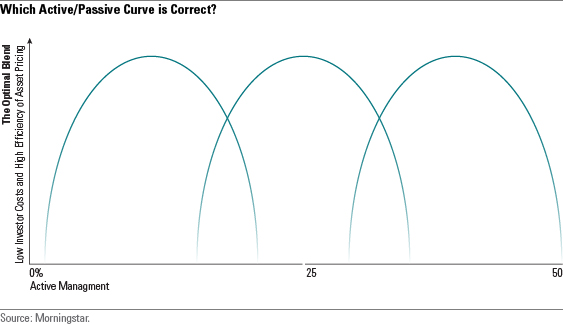

The same, it seems to me, can be said about the tipping point for active investing. As the Bernstein Research paper suggests, an active percentage of 0% is not ideal. In such a universe, investors' direct costs, in terms of fund expenses, would be very low, but the indirect costs of having capital allocated inefficiently would be very high. Conversely, if active investors made up 100% of the marketplace (as they did until a few decades ago), then capital would be allocated as efficiently as possible, but investor costs would be steep. That would also not be ideal.

Thus, somewhere between 0% and 100% rests the optimal level of active investing, from society's perspective. (Active managers such as AllianceBernstein, naturally, will have a very different perspective.) At that happy place, investors will pay the lowest possible fund expenses, because they will have the highest possible amount passively managed, but capital will be allocated reasonably efficiently, because of the presence of a sufficient number of active investors.

The picture of where that point lies looks like the chart of the Laffer Curve. I am fairly certain that the optimal share for active investors is less than 50%. It probably is much less. But really, we do not know. As with the Laffer Curve, the location (and shape) of the active-passive curve cannot be found.

Whenever active investment managers write about indexing, the suspicion arises that they arrived at the conclusion first, then searched for their reasons later. This Bernstein Research paper does nothing to change that view.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)