Making Contrarian Investing Work

Performance tends to persist in the short run, but betting on long-term losers can be a winning strategy.

A version of this article was originally published on June 25, 2014.

I have always admired contrarians. It isn't easy to think and act independently. Clients evaluate professional managers' performance against a benchmark, often over short windows. Those who underperform for a few years risk losing their clients, even if their investments ultimately pay off. That makes it difficult for many managers to make bold bets. Investing mistakes may also be easier to swallow when everyone is in the same boat. There is comfort in conformity, but this innate social desire can create opportunities for those who have the courage to think independently.

Fear and greed may create herding behavior. Investors tend to chase performance, buying securities that have recently done well and selling those with poor performance. This may partially explain the short-term persistence in asset returns, known as momentum. Generally, assets that have outperformed over the past six to 12 months continue to outperform over the next several months, while those that have underperformed continue to do so. That might suggest that a contrarian strategy wouldn't work well. Indeed, trading against momentum has historically been a losing strategy.

Yet, short-term momentum may push asset prices away from their fair values, leading to long-term reversals in asset returns, which is associated with the value effect. Assets with poor returns over long horizons eventually become cheap, and as a result, may offer better returns going forward. In a study published in 1985, Werner De Bondt and Richard Thaler found that stocks with the worst returns over the previous three to five years outperformed those with the best prior returns over the next three to five years. (However, a disproportionate portion of this outperformance occurred in January.) While this is a fairly crude approach to value investing, it illustrates that investors should fight the urge to extrapolate past performance into the future. Often, assets with dismal past performance offer the best opportunities. (Our own Russ Kinnel's "Buy the Unloved" series describes a contrarian fund strategy that attempts to take advantage of this effect.)

Even if asset returns mean revert on average over the long term, many individual securities will not because of changes in the competitive landscape that may permanently impair a company's fundamentals (think BlackBerry). Investors could more effectively diversify this type of company-specific risk by applying a contrarian strategy using exchange-traded funds, which hold many securities. To illustrate, I ran an analysis of contrarian strategies with sector, country, and asset-class indexes, rather than individual securities. Investors can gain access to each of these indexes through ETFs.

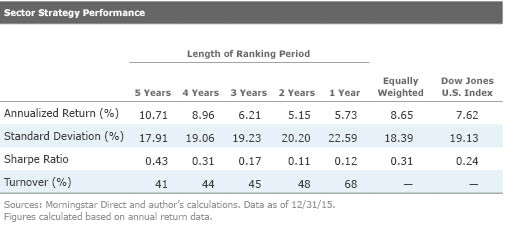

Sector Strategy It's no secret that sectors fall in and out of favor. To test whether investors could profit from systematically buying the most beaten-down sectors, I studied the 10 Dow Jones U.S. sector indexes. IShares' U.S. equity sector ETFs track these indexes, but investors can get similar exposure through Vanguard and SPDR sector ETFs. Once a year, I ranked the indexes by their returns over the previous five years and selected the three with the worst returns. I initially equally weighted these holdings but did not rebalance them until they were removed from the portfolio. For instance, if two positions were sold, the proceeds would be divided equally between the two new holdings. However, the existing holding would remain in the portfolio at its current weighting. This approach reduces turnover and makes the strategy easier and less costly to implement. The portfolio simulation began in December 1996 (using index return data starting in December 1991, the earliest available) and ran through 2015. I repeated this analysis using the return rankings over the previous four-, three-, two-, and one-year periods. The table below illustrates the results.

Consistent with De Bondt and Thaler's findings, a strategy that targets the sector indexes with the worst returns over the previous four- and five-year periods offered better absolute and risk-adjusted performance than the broad market-cap-weighted Dow Jones U.S. Index. However, the portfolio that targeted the sectors with the worst trailing three-year returns did not outperform. As the table above illustrates, the shorter ranking periods tended to have worse performance. These findings are consistent with negative short-term momentum and long-term reversals. Buying assets with poor short-term performance is like trying to catch a falling knife--it's probably going to hurt. But performance tends to mean revert in the long run. Therefore, a strategy of buying assets with a long stream of poor performance has a greater chance of success.

At the end of 2015, the contrarian strategy based on previous five-year returns held the basic materials, oil and gas, and telecom sector indexes. Investors can get exposure to these indexes through iShares U.S. Basic Materials ETF IYM, iShares U.S. Energy ETF IYE, and

Country Strategy Investors could apply a similar strategy using single-country index funds in their foreign-equity allocations. For this analysis, I included the MSCI country indexes for all members of the developed-markets MSCI World ex USA Index with a December 1969 inception date. This left 17 country indexes. Each year from December 1974 through 2015, I ranked these indexes by their returns over the previous five years and selected the five with the worst returns. I employed the same weighting and rebalancing approach as described for the sector strategy. As before, I repeated this analysis using four-, three-, two-, and one-year return ranking periods.

The portfolios of country indexes with the worst returns over the previous four to five years offered notable return improvements over the MSCI World ex USA Index. They were also more volatile but still managed to generate better risk-adjusted performance. Unlike the contrarian sector strategy, the portfolios formed on shorter-term return rankings slightly outpaced the benchmark, though they exhibited greater volatility. The one-year strategy did underperform when I increased the rebalancing frequency to monthly or quarterly, which suggests that poor performance tended to persist in the short term. Contrarian investing requires patience. Depressed assets may become cheaper in the short run, and it can take a long time for them to rebound.

At the end of last year, the five-year contrarian strategy held the MSCI Australia, Austria, Canada, Norway, and Singapore indexes. Investors can gain similar exposure through iShares MSCI Australia ETF EWA, iShares MSCI Austria Capped ETF EWO, iShares MSCI Canada ETF EWC, iShares MSCI Norway Capped ETF ENOR, and iShares MSCI Singapore ETF EWS. However, investors' fear can depress valuations and create more-attractive return opportunities going forward. Only Norway, Austria, and Singapore looked especially cheap relative to the group based on price/forward earnings ratios at the end of 2015.

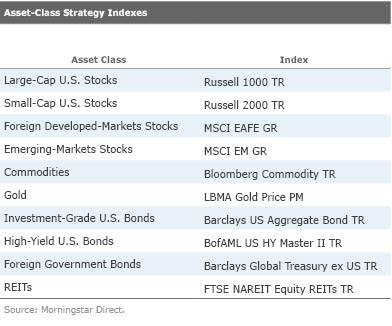

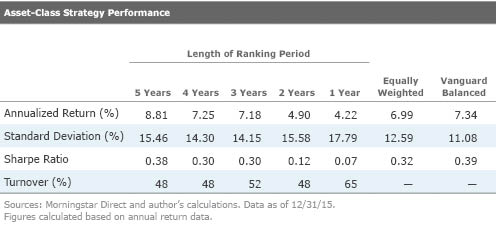

Asset-Class Strategy Tough though it may be, buying asset classes that have been unloved for few years also appears to be a winning strategy. For the asset-class strategy, I included the 10 indexes listed the table below:

I followed the same procedure as described for the previous two strategies. However, this strategy targeted the three indexes with the worst prior period returns. I ran the portfolio simulation from the end of 1995 (the earliest point at which five years of data became available for all the indexes) through 2015.

It is difficult to select an appropriate benchmark for an asset-class strategy. For the purposes of this study, I included both the

Despite the apparent success of the five-year contrarian asset-class strategy, it has some notable limitations. Most importantly, its risk profile can change dramatically over time, making it difficult to implement. It is also important to note that certain asset classes, like stocks, tend to have higher expected returns than others, like bonds, over the long-run. And even if bonds underperform for many years, their yield to maturity is an upper bound on their potential long-term returns. Investors might be able to more efficiently boost returns by allocating a larger portion of their portfolios to riskier assets with higher expected returns.

At of the end of 2015, the five-year contrarian asset-class strategy was invested in the MSCI EAFE, Bloomberg Commodity, and Barclays Global Treasury ex US indexes. Investors can gain access to these indexes through

Key Takeaways

- Betting on assets with poor recent performance is a bad idea. In the short term, momentum dominates, which means that recent laggards often continue to disappoint, and recent leaders remain aloft.

- However, assets that underperform over longer periods (four to five years) often eventually become cheap and poised to offer better returns.

- Investors can take advantage of these long-term reversals with a contrarian strategy using ETFs. This strategy may work better when investors consider valuations together with the contrarian signals.

References De Bondt, Werner and Thaler, Richard. "Does the Stock Market Overreact?" The Journal of Finance, Vol. 40, No. 3, 1985.

Jegadeesh, Narasimhan and Titman, Sheridan. "Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency." The Journal of Finance, Vol. 48, No. 1, 1993.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc.'s Investment Management division licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)