Labor Report Suggests a Very Different Employment Problem: Worker Shortages

The availability of enough workers may be the real problem behind the sluggish jobs report.

There wasn’t much economic data this week, so markets were largely focused on U.S. Federal Reserve Board Chair Janet Yellen’s speech on Monday. Like many analysts, she expressed concerns about last week’s jobs report but said that she felt the economy was still improving.

While we are relatively sure that the jobs report had some very real consistency issues, the Fed really can’t afford to take a chance. Interest-rate hikes seem off the table for now (and maybe for awhile), but Yellen was quick to indicate that the U.S. was on track for an increase, though there was no mention of timing. The markets generally reacted well all week, as the economy still appears to be doing OK.

There was a ton of seemingly wrong and contradictory data in last week’s jobs report. We highlighted some of the bigger issues, though readers dutifully reminded us that we missed some of our favorite criticisms of the report, including seasonal adjustment factors (the economy added a lot of jobs in May, but seasonal factors stripped out most of those gains). We didn’t spend as much time as usual on the criticisms because no matter how messed up the May report was, it seemed more important to focus on the slowing employment trends that have been quietly brewing over most of 2016.

Economic activity and employment have slowed, but not by a lot. The adjustments have been slow and erratic, but they are visible. Some of the adjustment was related to inventories that had gotten too high and needed to be brought in line with sales. However, we continue to believe that demographics, including a potentially shrinking working-age population, is what's really at work here. We are now relatively sure that the 2.4% GDP growth rate of the last two years cannot be sustained. Something closer to 2% seems more likely in 2016, and the path to a revival much beyond that is not at all clear.

About the only two significant pieces of data this week were the job openings and labor turnover report, which pointed to a worker shortage as one of the factors causing slow employment. The Congressional Budget Office also released federal budget data through May that continued to suggest a widening budget deficit in 2016 compared with 2015. Lower tax collections seem to suggest that the deficit for 2016 will be closer to $550 billion than the sub-$500 billion budget deficit projection when the year began. The deficit could approach 3% of GDP for fiscal 2016. The long-term prognosis isn’t great, clouded by the potential of higher interest rates and another recession just as baby boomer retirements peak.

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Report Suggests a Very Different Labor Problem Than the Employment Report Released Last Week Last week, we mentioned that a number of other labor market reports were at odds with the official government report for May. The Challenger, Gray & Christmas layoffs report (near record lows), low initial unemployment claims (lower again this week), and the ADP employment report all suggested a much stronger labor market for employees.

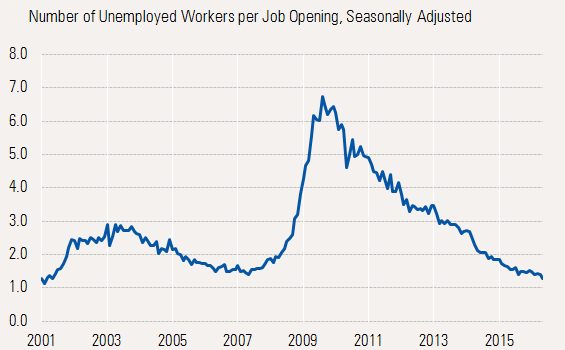

This week’s JOLT report for the end of April also suggested a more robust labor market. Job openings remained high, matching the recovery high of 5.8 million workers. The number of unemployed workers was just 7.6 million, just 1.3 times the number of openings. Except for a few months in early 2001, that ratio has never been lower.

Source: BLS

This would seem to suggest that the availability of enough workers may be the real problem behind the sluggish jobs report. That is also consistent with the higher wage rates that we have been seeing over the past year. A still relatively high ratio in construction and manufacturing is keeping the headline ratio from falling close to parity. Several industries now have more openings than unemployed workers searching for work.

That lack of available workers mean than openings continue to increase but hiring remains relatively flat over the past year.

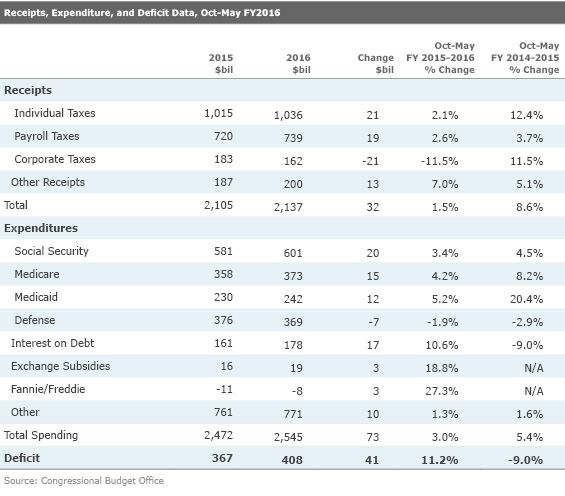

U.S. Budget Deficit Still on Track for Modest Deterioration Adjusting for weekend payment dates, the U.S. budget deficit for the first seven months of fiscal 2017 increased to $408 billion from $367 billion in 2016. With the big April tax collection month behind us, the deficit for the full year, ending September, usually increases modestly worse from May to September.

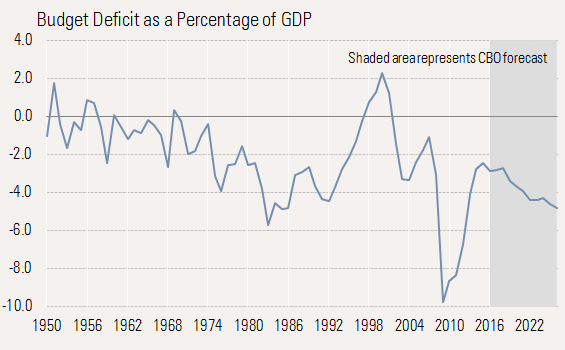

Again, taking into account varying payment dates, we suspect the full-year deficit is likely to be between $500 billion and $550 billion compared with $438 billion this year. The higher deficit levels would bring up the deficit as a percentage of GDP to 2.7% to 3.0% or more for the full-year 2016 from 2.5% in 2015. Fiscal 2016 will be the first year in the last five where the deficit has increased. At the height of the recession, the deficit got to over $1 trillion and almost 10% of GDP.

The May deficit data extends the patterns of the last year, with both diminished receipts and expenditure growth. Receipts are growing by just 1.5% year to date and expenses by 3%, causing the widening deficit. Lower collections from frequency spectrum auctions and lower fines on financial institutions are currently weighing on the data for 2016. On the other hand, fewer program losses on Housing and Urban Development loans are providing some short-term budget help.

The big issue on the receipts side is the slide in corporate taxes, which seems to be continuing. Retroactive and prospective changes in corporate tax policies (mainly investment and research-and-development credits) that were voted and implemented in December, have hurt collections. Adding insult to injury, declining corporate profits are also resulting in lower corporate taxes. Individual taxes, while continuing to increase, are still lower than expected because of smaller capital gains tax collections and small-business profits (which flow through individual returns in many cases).

However, spending has also been soft, limiting the damage of lower collections. Military spending has continued to decline, and Medicare spending growth has been lower than anticipated (though the annual true-up with insurers is yet to come). And interest expense, while higher, has not moved up as quickly as expected earlier in the year. Lower-than-anticipated inflation has also limited revenue and expenditure growth.

Looking ahead, the budget deficit is expected to be level for the next couple of years because of low interest rates and a pause in the surge of new Social Security recipients. However, as interest rates potentially move higher and the population of those turning 62 surges briefly, the deficit increases significantly.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

New Legislation, Recession, and Higher Rates the Key Worries in the Budget Outlook With the congressional logjam, there haven't been a lot of changes to law that have changed the deficit projections all that much. The largest factor that moves the deficit projections, besides law changes (or another bad recession) is increasing interest rates. Social Security spending is locked in actuarially; military spending, barring a conflict, is likely to remain low. Medicare and Medicaid spending could vary with healthcare inflation, but the government has some modest control of that inflation through reimbursement rates.

That leaves interest expense as the largest key unknown variable in the budget equation. The average interest rate on the outstanding public debt is currently about 2%. With interest expense running about $300 billion per year, a move from 2% rates to 4% rates would move the interest expense up dramatically in very short order (most U.S. debt is short-term or indexed to inflation). That means higher deficits and more debt and eventually more interest payments, which begin to feed on themselves and compound the deficit problem. Remember, the whole deficit is around $500 billion now, but interest expense, even without the effects of compounding, could go up by $300 billion with an interest-rate move from 2% to 4%.

Current projections assume interest rates paid move up from 2% or so now to 3%. But if the Fed keeps rates lower for longer, the deficit issue could be less severe than expected. And though a lot of the deficit is financed with very short-term debt, the average debt maturity is around six years, so a quick pop in rates won’t sink the budget immediately.

Obviously, a recession that could kick down receipts and raise expenditures is another big risk. Current projections assume moderate economic growth rates, perhaps even below trend. The trade-off in the calculations appears to be a lower growth assumption but not another large recession. That could quickly put a big dent in all of these deficit calculations. The hole created by the Great Recession still lingers in the form of all the debt remaining on the government’s balance sheet.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)