The DOL's Fiduciary Rule: Better Late Than Never

The world leads, the U.S. follows.

Not Enough If you haven't read Scott Cooley's column on the Department of Labor's Conflict of Interest Rule, also known as the Fiduciary Rule, you might wish to do so. It summarizes the rule's key points, discusses the changes that occurred from the proposed regulation to the final, and outlines several implications for investors. Scott put a great deal of work into that article; the rule is a 1023-page document!

This column covers different airspace. It is the view from up high.

The scene: Summer 1997, at a brokers' convention in Chicago. The keynote speaker, Nick Murray (who was still lecturing as of last year, at $10,000 per address), chastised audience members for being too humble. Why did they make house calls to visit potential clients? They should instead insist that prospects come to them. After all, doctors don't beg for business; they take appointments, and often make their customers wait, at that.

Well, yes. And doctors must gain admission into restricted medical programs, study for four years, and then spend three to seven years in residence. That is a significantly higher hurdle than the barrier erected for brokers, who must have a college degree, breathe regularly, and pass a securities exam. (Then again, only one of those three items is required for investment bloggers.) The analogy fails.

But setting credentials aside, there is another reason why Murray's comparison is inapt: professional standards. Doctors "must recognize responsibility to patients first and foremost." Brokers, in contrast, are under no such obligation to treat their customers with such respect. They merely need to recommend investments that are "suitable." The standard is not to be excellent; it is instead not to be obviously bad.

That, to understate the matter, is insufficient. It is unacceptable that a broker can move a client from a first-rate fund into a second-rate fund, with the legal protection that the latter fund might not be ideal, or better than what it replaced, but instead merely "suitable." The suitability defense can shield all sorts of trades that harm an investor's portfolio. It fails as a rule. It should be an ex-rule.

Enter the DOL fiduciary regulations. When implemented, they will mandate a best-interest test for all advice given to retirement accounts. The recommendations must be made for the betterment of the client. A similar requirement currently applies to advice within company-sponsored defined-contribution plans, such as 401(k)s. That higher standard will now be extended to IRAs, as well as to 401(k) rollovers. In each of those situations, financial advisors must make their recommendations in the best interests of their clients, and for rollovers (but, curiously, not within-IRA advice), they must document the reasons.

Investors Win This change clearly is a victory for investors. Roughly half of retail U.S. mutual fund assets will be protected by the new, higher standards. They will not prevent bad advice, of course, nor trades from lower- to higher-cost funds. But they do command that all advice, whether successful or not, be offered in good faith, and that the rationale for all trades, whether into cheaper or pricier funds, be recorded. Such precautions will inevitably lead to better overall outcomes.

As for the remaining half of retail assets, Jack Bogle believes that they will surely follow. The foot has been inserted into the doorway, he asserts, and eventually the entire door will be forced. “The words ‘fiduciary duty’ are now in fund regulations,” he says. “It’s only a matter of time before the SEC gets involved.” (The DOL has jurisdiction over tax-sheltered retirement accounts, but for other situations of investment advice, the SEC must take charge.)

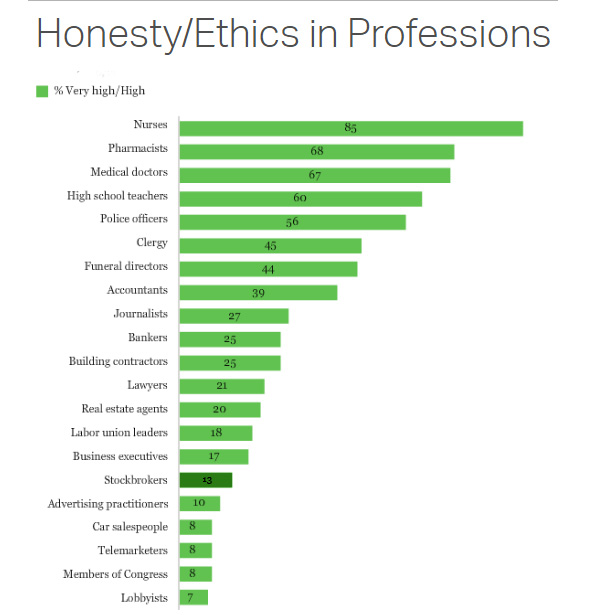

Advisors, Too What is less clear is that it is also a victory for financial advisors. The brokers who attended Nick Murray's 1997 presentation applauded him loudly; who doesn't love to be told that they are underappreciated? All in vain. Then, as now, the American public is not buying what Murray was then selling. A December 2015 consumer survey found that stockbrokers were trusted by 13% of respondents--as opposed to 67% for doctors. Even journalists (27%) and lawyers (21%) rated higher.

- source: Gallup

I can hear the objections.

“I am not a stockbroker. I am a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA), already held to fiduciary standard.” How many who answered the survey realize that? How many know that some financial advisors are governed by suitability, while others are fiduciaries? That is a rhetorical question; we both know that the answer is “depressingly few.”

"Just because I am a broker doesn't mean that I treat my customers badly." That is preaching to the choir. I like the traditional load-fund model. I've known many excellent brokers who did their homework; placed clients into well-run, relatively low-cost funds; received an upfront commission; and counseled patience. They were acting in their clients' best interests. But who believes me? Thirteen percent, it seems.

“Doctors have conflicts of interest, too.” Indeed, they have. However, the survey’s trust score is 67% to 13%. Advisors can listen to speakers tell them about how they are underappreciated or they can change things so that they become more appreciated. They have spent decades hearing the former. (Murray’s speech could be repeated verbatim today.) It’s very much time to try the latter.

Playing Catchup The United States has a history of mutual fund leadership. Its funds have the lowest overall fees and are accompanied by the best disclosure. The country that launched the world's first retail index fund does not normally lag behind, following others. But it does with fiduciary standards. Among the many findings of Morningstar's Global Fund Investor Experience Study is that 17 countries out of 25 decree that all financial advisors meet a fiduciary standard.

The U.S. will be among the lagging eight even after the DOL rule is implemented. It is, as this column’s headline states, late to the party. But at least it is now beginning to arrive.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CFV2L6HSW5DHTFGCNEH2GCH42U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7JIRPH5AMVETLBZDLUSERZ2FRA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YWKBIVULT5DGJEIGAJGBA6H5ZA.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)