Will Robo-Advice Replace Human Advisors?

A holistic model--with human and machine working together--holds the promise of better financial outcomes for all.

The emergence of robo-advice has generated enormous attention in the financial services industry and growing attention from investors. At first glance, the ability to deliver some sort of advice or asset-management solution over the Internet has the makings of a game-changer--something that could drive down fees, drive out all but the most competent and well-resourced financial advisors, and improve the financial lots of a hitherto unreachable majority of individuals in need of financial planning. In a world of vanishing defined-benefit pension plans and low interest rates, robo-advice’s arrival is timely. Even the least sophisticated long-term investors are increasingly aware that simply socking away money in a certificate of deposit may not be the best approach to achieve their financial goals.

However, like many issues in the financial services industry--where pursuit of novelty often trumps usefulness--the attention has focused more on the impact to current business models and less on how it might improve advice.

This is doubtless because the term "robo-advice" is very general and has been applied to everything from services delivering model exchange-traded-fund portfolios to more comprehensive solutions offering advice on savings, taxes, and the use of guaranteed income. This article will illuminate our view of advice and how we think robo-advice is best applied--specifically that a comprehensive, goals-based approach is needed.

What Is Robo-Advice? Robo-advice does not appear to have an agreed-upon industry definition. It's probably fair to say that the prototypical robo-advisor is one that uses a risk tolerance questionnaire to assign an investor to one of several quantitatively managed portfolios. A recent report from McKinsey & Co., "Digital Advisor: Delivering Personalized Advice in the Digital Age," argues for a different model: Flesh-and-blood advisors (not merely registered reps) work with clients via the Internet from virtual advice hubs. From the standpoint of the client, this allows for something approaching 24/7 access and the obvious convenience of not leaving the house. From the standpoint of advisors, it allows for administrative streamlining by pooling data and other functions. By and large, this is not materially different from the current model and seems likely to become industry standard for high-net-worth clients.

Therefore, robo-advisors look likely to comprise a heterogeneous lot. Their obvious commonality is the use of the Internet as the primary distribution mechanism. And if one takes that as the definition, then clearly robo-advice is here to stay. However, similar to the industry today, it is likely to exist in varying shades of completeness, with higher-touch/higher-service solutions existing alongside the low-touch/lower-services that we currently think of as falling under the robo-rubric and being priced accordingly.

Will robo-advice replace human advisors? At the lower end of the market, this seems likely, but for investors with comparatively complex financial pictures, it will not--at least not for the foreseeable future. For high-net-worth investors with complex financial profiles, the need for advisors to work in a cross-disciplinary fashion with accountants, lawyers, and the like does not now lend itself to the fully automated robo-model.

The near-term impact is likely to be a shaking out of the industry. Algorithmic robos are a threat to advisors whose primary focus is on picking investments and relying on third-party asset-allocation-policy portfolios. For asset managers, greater product specialization--and specialization focused on the needs of individual investors--and lower fees appear to be clear pressure points.

In November, asset-manager consultant Casey, Quirk & Associates published "The Roar of the Crowd: How Individual Investors Transform Completion in Asset Management." The authors argue that the marginal player in the money management industry is moving from the request-for-proposals-dominated biosphere composed of institutional consultants and their corporate and governmental clients to one driven by the individual investor. Whereas consultants mediated the institutional world (matching up institutional investors with asset managers), robo-advisors are likely to be the mediators in the new world. In fact, the authors estimate that individual investor assets will account for 90% of the asset-management industry and 120% of its flows in coming years.

Backstory Robo-advice is nearly as old as the commercial Internet. The earliest incarnation of robo-advice was probably ex-Smith Barney advisor Drake Mosier's 401(k) Forum in 1995, later rechristened mPower and ultimately acquired by Morningstar in 2003. 401(k) Forum explicitly sought to address the needs of defined-contribution investors. Using a then-sophisticated lifecycle investing model, investors were told what to invest in, how much to invest, and the likelihood of meeting their retirement goal. Financial Engines soon followed in the same space. Eventually, more entrants arrived with the goal of giving general investment advice over the Internet.

More recently, the success of startups such as Wealthfront and Betterment prodded the big, established players such as Fidelity, Vanguard, and Schwab to offer their own robo-advice and asset management. If nothing else, the presence of these market titans may be a harbinger of where the industry is heading.

Although this may change as millennials become a larger and more significant part of the workforce, recent research suggests that most investors are more comfortable working with a human advisor than with a computer. Some services such as Vanguard's Personal Advisor Services offer video-conferencing with an advisor. Financial Engines employs a bank of reps to aid retirement plan participants, and it recently announced the acquisition of the Mutual Fund Store with its advisors. But higher touch doesn't equate to low tech. Indeed, one of the great things about the advent of the algorithmic advisor is that the models used by these services can also be used by human advisors to aid them in their work. This is an important point. At the end of the day, all investment decisions come down to something quantitative, and to the extent that an advisor has a strong and coherent model to work with, the client will benefit. Human and machine can work together optimally.

Total Wealth and Lifetime Financial Advice If robo-advice is a general term, and if advisors need to differentiate themselves from one another, much of this will come down to investment methodology and philosophy. A robo-advisor could simply replace a traditional asset manager, asking a few questions about risk aversion and goals and building a portfolio of low-cost ETFs.

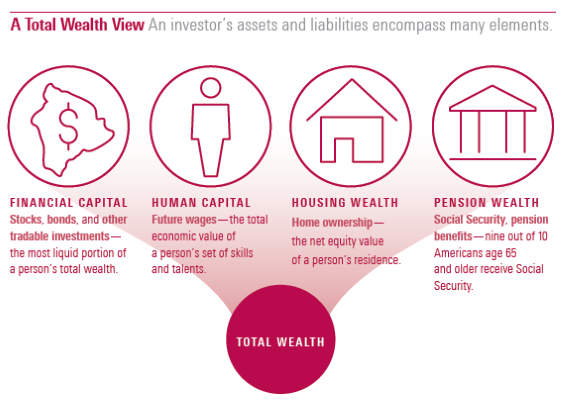

However, we think the robo-framework is best suited to a financial planning framework. It is important to take advantage of the new technology in a way that goes beyond efficient distribution. In the February/March 2015 issue of Morningstar Magazine, I outlined the concept of Total Wealth ("A New Chapter in Investing"). This framework seeks to capture all of investors' assets and liabilities and use the information to drive the portfolio-construction process.

The concept is generically identical (albeit broader and less detailed) as that outlined in "Lifetime Financial Advice: Human Capital, Asset Allocation, and Insurance," by Moshe Milevsky, Roger Ibbotson, former Morningstar chief investment officer Peng Chen, and Morningstar researcher Kevin Zhu. We will borrow the term Lifetime Financial Advice to help clarify our view of holistic financial advice and asset management. This approach is ideally executed through a quantitative model and, thus, is well suited to robos.

Total Wealth Redux The bulk of the asset-management industry is focused on performance relative to a benchmark, be it the S&P 500 or inflation plus a spread. This is perhaps unavoidable, as portfolio managers operate at a remove from the individual investor and have little knowledge of the goals and financial position of their investors. The advisory relationship, however, is direct and focused on maximizing the probability of meeting a set of future consumption goals as efficiently as possible. To do this, the advisor needs a model of an investor's assets and liabilities. This is what Total Wealth aims to do.

Within the Total Wealth framework, investors are defined as a bundle of attributes, such as their human capital (the current value of their expected future labor-based income), liquid assets such as their investment portfolios, and less-liquid assets such as housing, nonpublic equity interest in a business, or the ability to borrow. These represent budget constraints on consumption goals. An investor's actuarial profile can also be thought of as a budget constraint, as life expectancy and health are endowed in finite dollops. Investors also have consumption goals. These goals can be thought of as liabilities that need to be satisfied at different points in the future. All of this falls into the category of risk capacity and can be modeled using well-defined methods.

Investors also have preferences. These include things like "futurity," or how much value one places on consumption in the future versus the present; time substitution, which is the willingness of an investor to trade current consumption for future consumption; and risk aversion, or the degree to which investors dislike seeing negative shocks to consumption of which the expected variance of a portfolio's return stream typically serves as a back-of-the envelope proxy. In other words, investors care about the value of their current wealth to the extent that it can be mapped to a change in planned consumption.

This concept of preference is particularly meaningful when specifying the importance of a consumption goal. Goals represent units of "utility," but they are practically measured in current dollars. Different goals will have different importance to an investor. In this context, the idea of substitutability is important. An investor may rank a new car within the next two years as a top priority. He may specify the current cost of a new Lexus as the goal. However, if he is only able to buy a Toyota, the sacrifice in utility may be minimal and thus the importance of the dollar-valued goal--the price of the Lexus--goes down. Another investor may value the Lexus more and driving anything less may result in irreparable damage to her self-image. This investor is placing more importance on the consumption goal. This can be extended to the traditional concept of risk aversion in which otherwise identical investors respond differently to changes in the value of their portfolios.

Lifetime Financial Advice Redefined A crucial aspect of Total Wealth is that it represents a point-in-time estimate of an investor and the market. Future earnings, asset returns, investment contributions, and withdrawals are mere estimates of what models tell us is likely to occur. But the future is unknown. This is why constantly updating investor inputs and ensuring that investors are engaged in the investment advice process is critical. Markets perform differently than forecast, investors change jobs or receive a shock to their income, and people's health status changes. As with their human advisor counterparts, robo-led investors need to engage with the advice process through time. Continually updating inputs should be viewed as keeping the model on course, ensuring that its difficult estimates of the future are based on the most current and best information. The robo-relationship needs to last a lifetime; the model can't just estimate that lifetime at a single point. This requires effective tools to process investor information and elicit meaningful responses about things such as risk aversion.

To this end, we employ a platform that supports two applications, which constitute our delivery mechanisms for Lifetime Financial Advice: the Automated Portfolio Constructor, or APC, and the Wealth Forecasting Engine, or WFE.

As the name implies, APC constructs portfolios of funds and securities around an asset-allocation target. The core function is referred to as an "alpha-tracking error" approach, which is outlined in the article "Optimizing Manager Structure and Budgeting Manager Risk," co-written by Barton Waring, formerly of Ibbotson Associates. The function seeks to maximize a portfolio's excess return while minimizing excess risk relative to an asset class or factor model portfolio. The concept is simple, but applying it to a large number of portfolios with often idiosyncratic investment options is extremely challenging.

WFE is a cash flow modeling engine that, because it produces streams of expected cash flows over multiple horizons, is not reliant on complex or limiting mathematical approximations. It can be outfitted with any set of scenarios relevant to investors. It models the future by imitating it.

Both WFE and APC go back 15 and 10 years, respectively, and trace their roots to 401(k) Forum. Execution over this period hasn't been flawless, but their occasional stumbles have been educational and have given us the experience necessary to ensure their high standards of quality.

A key concept here is "modularity." Both APC and WFE can be used in concert or separately, and both are fundamentally agnostic engines that can accommodate any set of capital market inputs or investment options. While WFE can be used to do something as simple as forecast the value of a given portfolio--and we have clients who require nothing more than this function--we believe that it is best applied to Lifetime Financial Advice by continually applying the Total Wealth framework.

The concepts behind Total Wealth and Lifetime Financial Advice are not new. What's changed is the technology and the increasing comfort level of investors--both professional and novice--with such technology. More to the point, investors are becoming more comfortable with online commerce and with the fact that services once provided solely by humans can now be done algorithmically and over the Internet. It will not be all smooth sailing. Robo-advice awaits its first shock to confidence, but just as Long-Term Capital and Lehman failed to destroy the capital markets, it seems likely robos will survive such an event.

Enter Gamma Although the robo-framework, with its reliance on the Internet and Big Data, fuels comprehensive, goals-based approaches like our Total Wealth framework and Lifetime Financial Advice, a key component of the advisory industry remains unsatisfactorily defined: performance measurement. If an investor wants to achieve a retirement consumption goal, period-to-period performance of the investment portfolio isn't meaningful. And because the consumption liability is contingent and not fixed, developing an index to measure performance lacks the objective quality we associate with benchmark-relative performance. The best we can do is compare an investor's current portfolio with our model of the future to see if things such as asset allocation and savings rate are consistent with the model.

As mentioned above, this model could be an index. The utility function in the gamma framework, introduced by my colleagues Paul D. Kaplan and David Blanchett ("Alpha, Beta, and Now ... Gamma," published in the Journal of Retirement, December/January 2013), is based on changes in the expected value of a set of simulated income streams. The results are entirely dependent on estimates of market returns, investor contribution levels, fund performance, annuity rates, and really any other financial variable that can affect financial wellness. Different models could yield different results. That said, this approach easily allows investors to see how changing any of these variables helps or hurts their chances to achieve long-term goals. This isn't as good as stepping into the future, but it's far better than simply looking at index-relative returns or rolling three-year Sharpe ratios. Critically, it focuses on the consumption goal, accounting for things like savings, tax minimization, Social Security, and product allocation. Market tides are uncontrollable, and relative performance makes a minuscule impact compared with these other endeavors.

For example, life insurance and longevity insurance (annuities) can play valuable if not central roles in an investor's Total Wealth portfolio. Human capital is often the largest asset in one's Total Wealth portfolio. During the preretirement phase, the biggest risk an investor faces is death. If you die, so does your ability to earn a living, and thus dies your human capital. Conversely, dying upon retirement is the surest way to postcareer financial success: The overwhelming risk in retirement is that you'll outlive your assets. Life insurance serves to hedge human capital, and an annuity hedges outlasting your savings. Modeling the expected value-add of insurance can really be measured only in a cash flow simulation framework where a metric like gamma can show--often emphatically--the value of purchasing insurance to hedge one of these risks. The potential value of this alone on investor outcomes is enormous.

Monumental Opportunity Investors own a mix of liquid and nontradeable wealth. They invest today to consume tomorrow. They have needs with respect to financial goals and preferences with respect to the futurity and uncertainty of those goals. They also face constraints on wealth accumulation and the inescapable constant that shapes all financial problems, the Arrow of Time. In an uncertain world where pensions are increasingly being foisted onto the shoulders of individuals, people are in need of guidance on how to invest, plan, and consume optimally throughout their life. This is a complex problem, the solving of which technology makes possible and practical. The ability to instantly deliver a holistic recommendation to one's desktop has already begun to change the investing landscape and will profoundly affect investors' attitude and engagement with their financial future.

But if the delivery mechanism is all that has changed and the approach cannot break free of the traditional model portfolio paradigm, a monumental opportunity will have been missed. Robo-advice animates the Total Wealth and Lifetime Financial Advice frameworks. Looking closer to home, APC and WFE animate Morningstar's approach to financial planning, while gamma measures the ex-ante quality of advice. We believe the holistic model best serves investors and holds the promise of better financial outcomes for all.

This article originally appeared in the February/March 2016 issue of Morningstar magazine. To subscribe, please call 1-800-384-4000.

Disclosure Morningstar's Investment Management group includes Morningstar Associates, LLC, Ibbotson Associates, Inc., and Morningstar Investment Services, Inc., all registered investment advisors and wholly owned subsidiaries of Morningstar, Inc. All investment advisory services described herein are provided by one or more of the U.S. Registered Investment Advisor subsidiaries. The Morningstar name and logo are registered marks of Morningstar, Inc.

The information, data, analyses, and opinions presented herein do not constitute investment advice; are provided as of the date written and solely for informational purposes only and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security; and are not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate. Past performance is not indicative and not a guarantee of future results.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)