Index Funds: Presumed Guilty

But probably innocent.

The Allegations In his 2015 shareholder letter published last month, hedge fund chief Bill Ackman suggests that U.S. stock index funds may be creating two forms of instability. One is relative price disparity, between those stocks that are being rewarded with index-fund inflows and those that are not. The second is absolute price inflation, whereby index fund flows have created (or are creating--Ackman waffles on the timing) a market bubble.

(In addition to those items, Ackman attacks index funds for threatening the eventual health of the economy by being too easy on corporate chieftains. Unlike active investment managers, who are willing to hold laggards' feet to the fire, index funds tend to support entrenched corporate managers even if their results are poor, which will lead to complacency and weakness from corporate America. It's an intriguing notion, but outside the scope of this column.)

Such claims have become widespread among active managers, many of whom have made their cases less cautiously than Ackman did. Over the past couple of years, I've heard much about the disruptions caused by the index-fund boom. In the minds of many if not most market observers, U.S. stock index funds appear to be guilty of the charges.

Count me as a dissenter. Let's look at the two allegations.

Price Distortion This claim comes from the dominance of S&P 500 funds. Their success, writes Ackman, has produced stock-market haves and have-nots--a form of investment inequality, if you like. In putting their huge new inflows to work, the S&P 500 funds push up the prices of those happy 500 stocks leaving the rest of the market to languish.

I'm skeptical. Yes, S&P 500 funds are the top-selling flavor of U.S. stock index funds. But then again, the S&P 500 has a very large appetite. Accounting as they do for about 80% of overall U.S. stock-market capitalization, S&P 500 companies can and should receive the lion's share of incoming index-fund assets.

To put that figure into perspective, last year Vanguard's non-S&P 500 index funds received 37% of all U.S. stock index-fund sales. The year before, they had 32%. While most of those monies landed in

If S&P 500 funds have boosted the relative fortunes of the companies in that index while their cash-deprived smaller rivals have languished, then logically the S&P 500 should have grown its share of the total U.S. stock-market capitalization. It hasn't. As previously noted, the index (per S&P's website) traditionally has been worth about 80% of the U.S. market. Today, it's 79%.

Market Bubble Ackman doesn't directly make the case that index-fund inflows have created an overall market bubble. He couches the issue in relative terms: "As the most popular index funds' constituent companies become overvalued, these funds' long-term rates of return will likely decline, reducing investor appeal and increasing capital outflow. When capital flows reverse, index fund returns will likely decline, reducing investor interest, further increasing capital outflows, and so forth."

Either way, he gets to the same place. If the value of four fifths of the U.S. stock market has been puffed up by index-fund asset flows, and what has gone up must come down, then that qualifies as an overall bubble. Yes, there may be safe pockets, as with the late 1990s' New Era bubble, when small, value-oriented companies offered a refuge, but by Ackman's thesis any general U.S. stock-market fund (whether indexed or not) is courting trouble.

Trouble may indeed be coming, but not because of fund sales. If the thesis is that high fund asset inflows have inflated the marketplace, by pushing up prices to artificial (and temporary) levels, then it matters not whether those inflows have come through indexing or active management. That is, if every dollar going into index funds is matched by a dollar that is redeemed from active funds, then U.S. stocks haven't been moved at all, in aggregate, by fund flows. Some stocks may benefit more than others from the active-to-passive shift, but the net effect is zero.

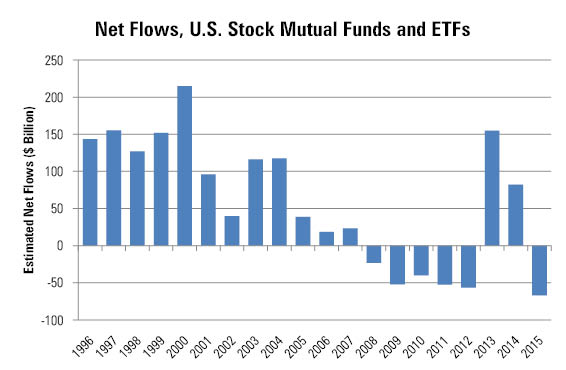

Or, in the case of funds and the U.S. stock market, less than zero. The chart shows the net asset flows into U.S. diversified equity mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, by calendar year, from 1996 to 2015.

Source: Morningstar

Hmmm. The thesis that inflows into indexed mutual funds and ETFs have inflated the value of U.S. stocks comes at a time when the evidence suggests just the opposite. In six of the past eight years, mutual fund/ETF sales have been negative. More money has been redeemed by those funds, in aggregate, than has been sold. So how on earth are funds propping up U.S. stock prices?

You got me.

To wrap up: I don't see this time as being different. Mutual fund/ETF inflows always influence the market. They are unevenly distributed among the different flavors of funds, thereby creating relative winners and losers. In addition, they vary in absolute levels from strongly positive to strongly negative, which gives the overall market a headwind or tailwind. That was true 20 years ago, and it's true today. That index funds are the driving source of those effects rather than active funds is of interest, but I think not relevant to the analysis.

Yankee, Stay Here! Say "yeast." Now take out the "t." That is how New Zealanders pronounce the word "Yes." You would think that given this handicap, they would refrain from mocking others' accents. But no. In New Zealand, Australians are under constant, unceasing attack, including for their speech. (I was told that there's nothing funnier than hearing an Australian say "fashion show"--such is Kiwi humor.)

It's a faux battle, though. Countries that argue the relative merits of Vegemite versus Marmite are too alike to be real enemies. Australians are not New Zealand's true tourist villains. Nor, I am happy to say, are Americans. We have been displaced by Asia's universal baddies: mainland Chinese. It's nice to feel wanted.

It's also nice to be publishing again. (Yes, really.) Thanks for reading.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)