The Cost Matters Hypothesis

While markets’ efficiency will be forever questioned, there is no question that the costs we incur in investing deduct directly from our returns--it’s simple subtraction.

A version of this article was published in the August 2015 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of ETFInvestor here.

In a 2003 contribution to CFA Magazine, [1] Vanguard founder and former CEO Jack Bogle introduced the cost matters hypothesis, or CMH. Bogle presented his theory as a substitute for the efficient-market hypothesis, or EMH, as a means of framing the task facing investors aspiring to beat the market:

We don't need the EMH to explain the dire odds that investors face in their quest to beat the stock market. We need only the CMH. Whether markets are efficient or inefficient, investors as a group must fall short of the market return by the amount of the costs they incur.

This same harsh math was elegantly laid out by William Sharpe in his seminal 1991 piece "The Arithmetic of Active Management" [2]:

If 'active' and 'passive' management styles are defined in sensible ways, it must be the case that

> before costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will equal the return on the average passively managed dollar;

> after costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will be less than the return on the average passively managed dollar.

These assertions will hold for any time period. Moreover, they depend only on the laws of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Nothing else is required.

Not a Hypothesis, a Fact Fact: Costs matter. While markets' efficiency will be forever questioned, there is no question that the costs we incur in investing deduct directly from our returns--it's simple subtraction. Fees are the clearest hurdle facing portfolio managers. The more they charge for their services, the harder they will have to work to earn back and ultimately justify their fee. As such, there is, on average, an inverse relationship between fees and managers' success. This is difficult for many investors to grasp as they assume that "you get what you pay for," but as Bogle has said, in investing, you get what you don't pay for. Paying Ferrari prices will likely land you behind the wheel of a lemon. Meanwhile, paying lemon prices will probably put you in control of a Honda--efficient, reliable, safe, an all-around good value, though not something you'll be bragging about at a barbecue.

At ETFInvestor, we recently began to document this relationship in our Active/Passive Barometer report. In this report, we measure actively managed funds' performance against a blended benchmark composed of their passively managed Morningstar Category peers (including exchange-traded funds and index mutual funds). Those active funds that survived the period (that is, they weren't closed or merged away) and generated performance that exceeded that of their average passive peer were deemed to have succeeded.

The second column in Exhibit 1 shows active funds' success rates over the 10-year period ended Dec. 31, 2014. As you can see, the majority of active managers across all but one category failed to best their passive counterparts.

Of course, no one sets out to pick an average manager. So how might investors improve their odds of picking a winner? Sorting by fees is as good a first step as any. In the third and fourth columns of Exhibit 1 you'll see the success rates for the lowest- and highest-cost quartile of funds across each category. In all but one case, the lowest-cost funds in a category had above-average success rates and far greater chances of beating their average passive peer than the highest-cost funds in the category. Fees matter.

Broken Record? If I sound like a broken record, it's because investors haven't found this particular lyric to be as catchy as one might expect. In 2010, a trio of Ivy League professors published a study [3] that examined why investors choose high-cost index funds. The group they studied was composed of Harvard staff and Wharton MBAs. Their experiment involved giving each participant a fictional $10,000 to invest across a lineup of S&P 500 mutual funds. Participants were rewarded on the basis of their performance. Sounds simple enough, right? S&P 500 exposure has become a commodity good. So the winning strategy would be to simply put all your Monopoly money in the lowest-cost option, let it ride, and claim your prize. As it turns out, this wasn't quite so simple for the Ivy Leaguers that took part in the study. In fact, the professors found that their test subjects "overwhelmingly fail[ed] to minimize fees."

While the findings of this study paint an unflattering picture of investors' grasp of the importance of fees, real-world evidence is increasingly telling a different story. In a survey of fees across the U.S. funds industry that my colleague Mike Rawson and I co-authored in 2015, we found that 95% of aggregate inflows into U.S. mutual funds and ETFs over the past decade have gone into those funds occupying the lowest-cost quintile of their respective categories. That said, there is still work to be done. As of the end of January, there was still more than $70 billion invested in index mutual funds tracking the S&P 500 that charge fees greater than 0.20%.

There Is More to Costs Than Just Fees Costs matter, but fees are just the tip of the iceberg. The other major costs of investing are related to taxes, advice, and investor behavior. These costs are more difficult to control than fund fees and, when added together, can be many multiples what an investor pays out in the form of annual expense ratios.

Taxes are an inevitable feature of investing. They cannot (legally) be evaded, but smart planning can help to defer and/or avoid them in such a manner as to maximize aftertax wealth. ETFs, and index funds in general, are inherently tax-efficient to the extent that their low levels of natural portfolio turnover result in relatively fewer taxable capital gains distributions vis-a-vis traditional actively managed funds. ETFs' in-kind creation and redemption mechanism adds a layer of tax efficiency. This mechanism allows ETF portfolio managers to purge low-cost-basis securities from their portfolio. However, ETFs won't vaporize tax liabilities. Investors will still pay taxes on dividends and any capital gains distributions that they might pay out. They will also be on the hook for capital gains taxes when shares are sold at a price higher than their original purchase price.

For those who need a helping hand in managing their investments, the cost of advice can also be significant. It can also be difficult to know how much you're paying for that advice. Dollars and cents disclosure is a rarity in the world of financial advice. If you work with an advisor who spells out how much he is charging you, congratulations, you've probably found a good one. If you don't know how much you're paying your advisors, here's my advice: Ask them how they get paid (a flat fee, a percentage of assets under management, and so on.) and how much. You might be surprised by their answer.

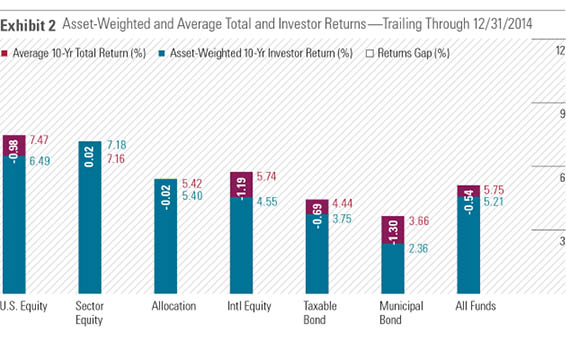

Perhaps the single greatest cost investors incur is self-inflicted: It stems directly from their own behavior. My colleague and Morningstar FundInvestor editor, Russ Kinnel, has been documenting this cost for years now in his annual "Mind the Gap" study. Russ has shown that investors, through their own ill-timed decisions, wind up experiencing returns (cash flow-weighted returns) that lag the performance generated by the funds they invest in (time-weighted returns). Fund investors appear to have a nasty habit of buying high and selling low.

How can investors try to minimize the costs associated with their own bad behavior? Russ' work shows that behavior gaps tend to be narrower for lower-cost funds. This relationship is partly driven by the prevalence of index funds in the lowest-cost cohort. In the case of the largest equity index fund,

Low fees, tax efficiency, and clear expectations give ETFs and index mutual funds a huge competitive edge when it comes to minimizing costs and maximizing wealth. This is not a hypothetical--the data back it up.

[1] Bogle, J.C. 2003. "Whether Markets Are More Efficient or Less Efficient, Costs Matter," CFA Magazine, November/December 2003, P. 6.

[2] Sharpe, W.F. 1991. "The Arithmetic of Active Management." Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 47, No. 1, P. 7.

[3] Choi, J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. 2010. "Why Does the Law of One Price Fail? An Experiment on Index Mutual Funds." Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 23, No. 4, P. 1405.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc.'s Investment Management division licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)