The Squeeze on Fund Expenses

Will it spread to financial-advisory fees?

The Race to the Bottom On the front page of Wednesday's The Wall Street Journal: "Mutual-Fund Fees Tumble Toward Zero."

Well, sort of. More accurately, mutual fund investors' willingness to pay fees is tumbling toward zero. As a result, most existing funds have become dinosaurs. They do not and cannot sell new shares, unless they are one of the very few to post unusually strong returns. All the assets flow to the minority of existing funds that have low expense ratios (that is, index funds and institutional share classes), and to newly launched funds that sell on the cheap.

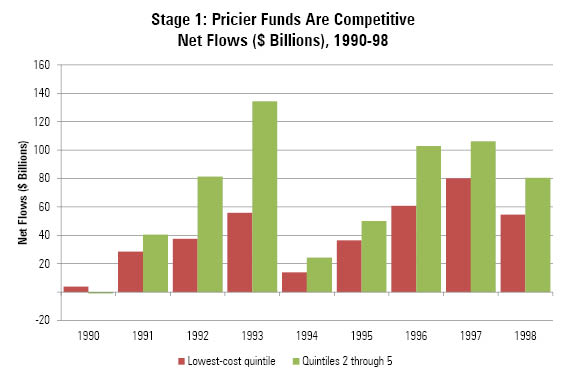

As implied by the verb "tumble," things weren't always this way. Two decades ago, bargain funds gathered somewhat more than their share of new sales, but they were far from dominant. The chart below portrays annual net inflows into U.S. mutual funds, sorted by expense quintiles (relative to the entire universe of stock and bond funds). The 20% of funds that fell into the lowest quintile are the red bars, while the remaining 80% of funds are green. Red fared better, overall, given its smaller constituency, but the battle was competitive.

Source: Morningstar.

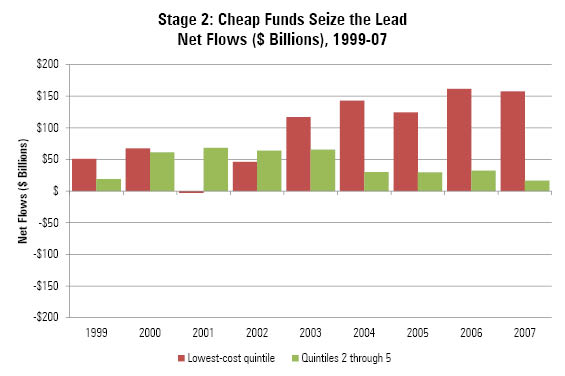

By the late 1990s, the word was starting to get out. Vanguard's Jack Bogle had become the industry's most visible (and trusted) spokesperson. The academic argument that expenses were the most important determinant of a fund's future performance--indeed, said some, the only important determinant--was beginning to circulate broadly, among both financial advisors and the media. Cheap funds' ascent was briefly interrupted by the 2000-02 bear market, but by the middle of the decade the bargains ruled.

Source: Morningstar.

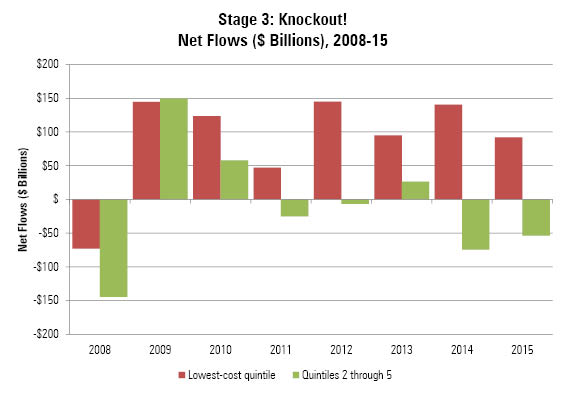

Today, the pattern has become even more pronounced. Once again, a bear market temporarily upset the picture, as assets flowed into relatively pricey, actively managed bond funds following the 2008 crash. But that habit quickly ended. Since 2010, the cheapest-quintile funds have gobbled every penny of net mutual fund sales. Indeed, they have consumed more than 100% of that amount, as the remaining 80% of mutual funds have suffered aggregate net redemptions.

Source: Morningstar.

These pictures flatter the dinosaurs, as they come only from mutual funds and do not include exchange-traded funds. Because ETFs are a recent development and come with markedly lower expense ratios than are carried by traditional mutual funds, their inclusion would dramatically strengthen the 25-year pattern. In truth (all right, metaphoric truth rather than literal truth), cheap funds haven't merely scored a knockout; they have put conventional funds into a coma.

From which, I believe, there will be no recovery. There's nothing to indicate that the pattern will reverse. The higher-cost funds still trail in performance, to receive few recommendations, to be eliminated by financial advisors' screens, and to generate unfavorable publicity. It's over for them. The larger funds will continue to exist, for decades, because of the powerful force of inertia. But eventually, their current shareholders will expire. And there will be no new generation to replace them.

Funds First, Financial Advisors Next? Which has me wondering … will the same process occur with financial-advisory fees? Roughly speaking, that industry's percentage-of-assets charge resembles that of the typical mutual fund, at about 1% per year. But unlike the dinosaur funds, advisors who charge such fees are thriving. In the financial-advisor industry, there's nothing like the fierce price wars that have occurred with mutual funds.

The reason for the discrepancy is obvious. Mutual funds are public entities. They are registered, tracked, measured, and scored, not only by industry trackers such as Morningstar, but also by academics. As with professional athletes or national politicians, the performances of fund managers are openly compared and discussed.

In contrast, financial advisors operate quietly, away from the spotlight. There is no Morningstar of the financial-advisory industry. No company tracks the results of individual financial advisors to compile their clients' performance results. No organization sorts financial advisors by the fees that they charge and attempts to ascertain if that money is well spent, or if investors would be better off seeking advisors who offer cut-rate deals.

Nor will one, not in the foreseeable future. The required public disclosure for the performance of financial advisors' clients is much less than what is demanded of mutual funds. (Indeed, it barely exists at all.) There's nowhere near enough information to permit an outsider to measure and compare. A company that attempts to track the results of financial advisors is a company that will soon go bankrupt.

That is not a complaint. I understand that evaluating the performances of many advisory clients, each of whom has different risk tolerances and portfolio constraints, is a much sterner task than comparing the gains on one U.S. stock fund against those of another. It may well be impossible to do that job fairly. There are good reasons why mutual funds are governed by the strict reporting requirements of the Investment Act of 1940, and financial advisors are not.

It is, instead, an explanation of why the price pressures that have been placed on mutual funds are unlikely to affect financial advisors to the same degree, even though for the performance of an investor's portfolio, a 1% reduction is a 1% reduction. No matter where the money is paid.

However, there will be something of a squeeze on advisors. Until now, they have enjoyed the luxury of having no natural enemies. Yes, I realize that many advisors regard the financial press as an enemy, as financial writers typically write to a do-it-yourself audience, and therefore downplay the need for professional advice. But the press is a faux foe. The press cares first and foremost about readers; advisors are important to it only insofar as they get in the way.

I, Robot The new breed of robo advisors, on the other hand, directly competes with financial advisors. The robo advisors want the traditionalists' clients. They want those assets. Their campaign is only beginning. As it strengthens, as their businesses grow and they gather more media attention, their voices will be louder. The attack on financial-advisory fees will commence.

Thus, to address this column's initial question: Yes, I believe that the battle that has been waged against mutual fund expenses will begin to turn to financial-advisory fees. The pricing pressure will increase. However, because it is not possible--and will not be possible--to dispute the claims of financial advisors with data, the financial-advisory business will offer stiffer resistance to change than the fund industry did.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)