Do Declining Oil Prices Signal a Problem for Stocks?

They have not generally, but that might be changing.

The Question On Jan. 21, former Federal Reserve vice chairman Alan Blinder asked the obvious question: Since when is cheap oil a bad thing? One would think that it's positive news for a vital commodity to become readily available. True, those countries that export the commodity will lose revenues, but the world overall will gain wealth. Yet in recent months the major stock markets of the United States, Europe, and Japan--all net importers that would seemingly enjoy the full benefits of oil's price decline--have slipped when oil prices have declined.

This has happened, says the Wall Street consensus, because oil prices are the canary of the global economy's coal mine. If they are slumping, that indicates slack demand and upcoming economic woes. Most Wall Street economists have therefore been downgrading corporate earnings forecasts and upgrading their probability of a U.S. recession.

Blinder begs to differ. In his view, as given in The Wall Street Journal, stock markets have "got the direction wrong." He continues, "Ask yourself: When the price of something you buy goes down, does that make you better off or worse off? No, it isn't a trick question. The obvious answer is the correct one. Other things equal, each of us is better off when the prices of things we buy, including oil, go down."

Blinder adds, "So collapsing prices are terrible news for Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, and perhaps for Texas and North Dakota. But they are good news for most American businesses." He shrugs off job losses in the U.S. oil industry as being inconsequential, with that sector accounting for 0.8% of U.S. nonfarm jobs, and points out that energy stocks are but 6% of the S&P 500. "The markets," he concludes, "are scaring themselves."

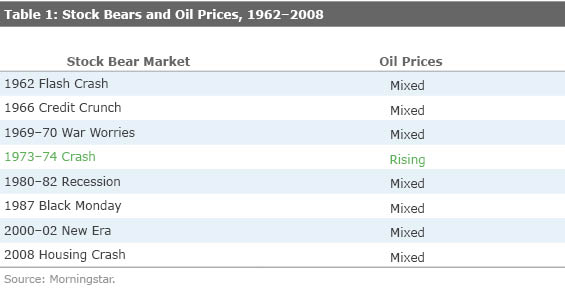

Stock Bear Markets Stock market history supports Blinder. Of the eight bear markets since John F. Kennedy became President, none were accurately forecast by oil prices.

In the 1960s, oil could not flash any type of indicator, since its price barely moved. That changed entering the 1970s, but unfortunately for its prowess as a signal, oil botched the 1973-74 stock crash. Oil prices were quiet throughout 1973. By the time that year ended, stocks had already shed 25% of their values. Oil then soared in 1974, as stocks continued to tumble--a correlation, to be sure, but in the wrong direction.

Oil proved no more helpful in the 1980s. Oil slipped modestly from its record high during the 1980-82 bear market (but not enough to serve as an indicator) and bounced up and down in 1987. Fifteen years later, as the New Era stocks plummeted, oil had a mixed showing. It did join stocks for the first 18 months of the downturn, but then it rallied sharply entering 2002. Stocks promptly got thrashed.

Even the apparent victory of 2008 was pyrrhic. Most recall how the third-quarter financial panic was accompanied by plunging commodity prices--vivid omens of the ensuing global recession. But as before, this indicator arrived late. Oil spiked through the middle of that year, hitting its all-time peak in June. By then, stocks were already officially in a bear market, having slipped 20% from their highs.

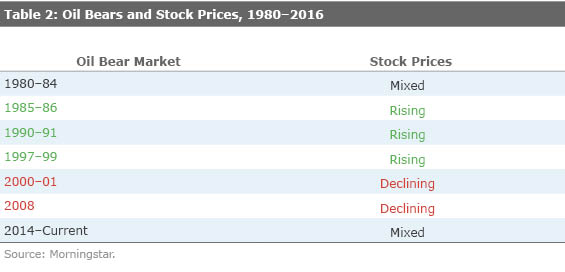

Oil Bear Markets Of course, the oil/stock relationship works both ways. Perhaps the duo yields more information when viewed from the opposite perspective. We have so far sought each case of a stock market downturn and then asked how oil fared at that time. One could just as reasonably look at each instance when oil dropped in price and then ask what that behavior said about stocks. Looking at the matter from that angle might strengthen the case for the oil signal.

And it does.

There were no significant oil price declines between the end of World War II and 1980. Since then, there have been several. The first four "oil bears," as I call them, failed to predict stock market slides. In fact, they mostly preceded stock market rallies. Admittedly, the long 1980-84 descent accompanied mixed rather than outright bad stock results, but the next three times oil prices fell--early 1986, early 1991, and early 1999--stocks would go on to post healthy gains over the next 12 months.

The two most recent dips in oil prices (prior to the current decline, that is) lend credence to the Wall Street consensus, however. The 2000-01 downturn accurately presaged 2002's stock market problems. Then, although it did time its signal rather closely, the summer 2008 oil price reversal did arrive before equities collapsed in late September. Perhaps even keen believers of the oil price signal would not have been able to exit stocks in time, but at the least, it must be granted that when oil started to head down rather than up, that particularly bad stock market news awaited.

Conclusion The longer-term history overwhelmingly sides with Blinder's claims. However, over the past 15 years, it does seem that oil prices may indeed be a negative signal for stock prices.

Blinder's economic argument remains intact. There's no question that given enough time, lower oil prices translate to greater global wealth, higher U.S. corporate profits, and extra cash in the wallet for U.S. consumers. (Effectively, the decline in oil prices is akin to a tax rebate, but one that does not come at the cost of hiking U.S. debt.) But Wall Street may be correct about the short term. The oil price slide clearly reflects a drop in aggregate demand that, less clearly, might lead to further stock market losses.

My take: Blinder is right, and yet he is wrong. His question was well-considered, in that the markets--and market commentators--seem to be taking at face value a relationship between oil and stock prices that is anything but reliable. However, Blinder is too certain of his position. The matter is not as straightforward as he presents. Unlike with most previous decades, when inflation was the threat, today's main danger appears to be low demand. In that case, sinking commodity prices might well be the canary.

For this debate, I am not fully convinced by either party. Each speculates: Blinder that history will remain the same, and the Wall Street consensus that this time will be different. At this time, I see no reason to prefer one form of speculation to the other.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZM7IGM4RQNFBVBVUJJ55EKHZOU.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_d910b80e854840d1a85bd7c01c1e0aed_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/K36BSDXY2RAXNMH6G5XT7YIXMU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)