With Indexing, Being Dumb Can Be Smart

It may not be wise to seek the single "best" approach.

Splitting the Difference In the early 1990s, Morningstar created the Morningstar Style Box to describe U.S. equity funds. The style box sorted stocks by two dimensions: by size, from large to small, and by cost, from growth to value. (In this column, I reword what typically is called "style" as "cost" because that is ultimately what distinguishes growth from value stocks, the cost of the stock.) Measuring size was straightforward. Determining the cost axis was a bit trickier. Some value managers sought cheap earnings, while others hunted for bargain assets. Cost, it seemed, could be defined by either price/earnings or price/book ratios.

Morningstar used both. Thanks in part to the research of Eugene Fama and Ken French, who published their seminal work on the sources of stock returns in 1992, P/B had become the academic norm. However, many value fund managers invested otherwise, so Morningstar did not choose the single tactic of P/B. Instead, it split the difference. A stock's cost score was assigned 50% on P/E ratios and 50% on P/B ratios. (The methodology is now considerably more complex, although perhaps not better.)

Whether combining the calculations made for a stronger investment style box is up for debate. But it certainly would have made for a stronger investment.

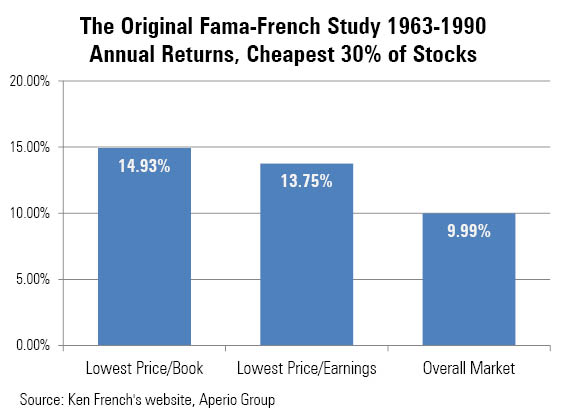

When Fama and French assembled their original numbers, using data from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, using the P/B ratio had indeed led to superior returns. The indexing firm Aperio Group--which authored a paper that provides this column's numbers--calculated the performance from the original Fama-French data set (1963-1990) for two flavors of value style strategies: 1) the cheapest 30% of stocks as defined by P/E, and 2) the cheapest 30% defined by P/B. The former beat the overall stock market by almost 4 percentage points per year but still trailed the latter.

But P/B's victory looked to be arbitrary. Why would buying companies for undervalued assets be more profitable than buying them for low-cost earnings? There was no adequate explanation--indeed, few explanations were attempted at all. There might be a permanent factor embedded in those three decades' worth of data, or the result might have been an accident. From the investor's perspective, as well as that of the investment style box creator, there was not a strong reason to prefer P/B over P/E.

And, indeed, the pattern reversed.

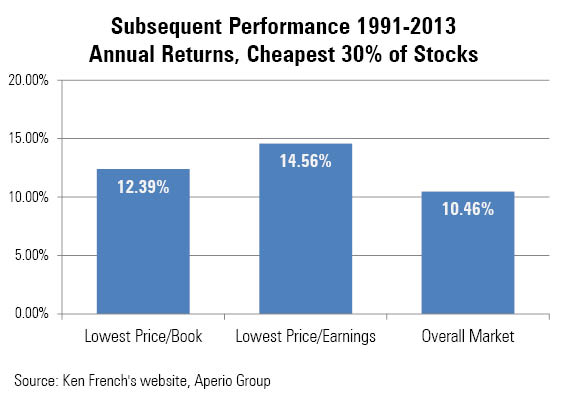

Over the next 23 years, the basic finding of Fama-French repeated: Low-cost stocks once again triumphed. However, the relative merits of the tactics reversed. In recent years, the stocks selected through P/E ratios have beaten those chosen by P/B, and with a larger margin of victory to boot.

As Aperio points out, a larger data set (besides adding the 1990s and 2000s, French's website has also retrieved the 1950s) reverses the initial Fama-French result. For the fullest time period that is available, from 1951 through 2013, selecting the lowest 30% of stocks through P/E ratios, rather than by P/B ratios, was rather comfortably (150 basis points per year) the better approach.

One could seize upon those results, launch an exchange-traded fund that buys low P/E stocks, and trumpet the back-tested results as proving the fund's superiority to other value strategies. (If that hasn't been done already, that is.) But that would be moving from the frying pan to the broiler. Believing in low P/E rather than low P/B is just as arbitrary.

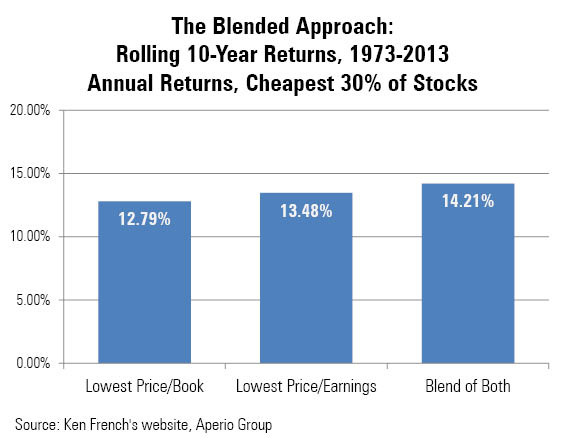

Rather than hop from one value style tactic to another, depending upon how the numbers change, it's better to play dumb, assume that the two approaches are of equal merit, and invest accordingly. In evaluating 40 years' worth of rolling 10-year periods from 1973 to 2013, Aperio found that portfolios formed by blending the two measures outgained portfolios formed by either single method.

These findings echo those of my New Year's Day column, which also looked at how different implementations of value strategies led to different results. In hindsight, though, that column was perhaps overly optimistic in hinting that that investors could rationally sort through the evidence and decide on a single best approach. Maybe they can. But it's probably wiser to hedge that bet.

Imperfect Justice In response to Friday's column on 401(k) lawsuits, Fred Campbell asks, "What, if anything, can one do if in a small 401(k) plan with poor management? Adding plan costs of 0.75% to the expense ratios of the underlying funds, I pay around 2% annually to invest in any of our plan's actively managed funds. At my request, the company added index-fund options, but these funds have 0.60% management fees. Adding plan expenses to that, I am paying 1.35% for an index fund! Do I have any recourse?"

Yes and no.

Yes, in that Fred Campbell's company might be able to lower the plan's cost by selecting another provider or by pressuring the current provider. Even if those expenses go unchanged, the company could improve participants' results by choosing to absorb some (or all) of that 0.75% in plan costs. So employees should be vocal; the squeaky wheels may get greased.

No, in that the economics are not friendly. Recordkeeping for small-company plans is not a high-profit business, because there are high up-front costs to acquire customers, and the revenues associated with each plan are not large. Also, the class-action lawsuits that are pressuring the costs in the large-plan market have no bearing on smaller companies. The legal firms feed on elephants, not ants.

In short, the 401(k) marketplace is bifurcated. Large plans are good and are rapidly getting better, while small plans are inferior and are changing more slowly. The best way to get a strong 401(k) plan is to take a job with a bigger company. The politicians who oversee the 401(k) rules won't admit to that, of course, as they profess to support U.S. small businesses, but such is the reality.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)