The Case for Market-Timing

It can make sense, if done with humility.

The Devil Advocates Two months ago, I called market-timers "circus clowns minus the funny suits." My argument: "Even when market-timers dodge the bear market, they inevitably miss the ensuring bull. Their track record is terrible, and that of their cousins, tactical asset allocators, is not much better. There is a reason 99.9% of mutual fund assets are invested in funds that don't attempt to time the market."

That column generated a polite rejoinder from Bob Desrochers: "When things get frothy I lighten up, wait a predetermined amount of time, and get back in. Works a lot better than buy and hold. Can I pick tops/bottoms? Of course not, but I can avoid much of the loss … the trick is getting back in without emotions interfering with the plan." (On that final point, we fully agree.)

More formally, three researchers at AQR Capital Management support the art of market-timing in November's shrunken Institutional Investor. (There's not much business these days for magazines that neglect the Kardashians.) To be sure, the article "Back in the Hunt" pounds no tables--it merely suggests. The authors (AQR founder Cliff Asness, Antii Ilmanen, and Thomas Maloney) advocate modest adjustments rather than all-or-nothing trades. Write the authors, "If you sin, then sin only a little."

Still, it's a defense.

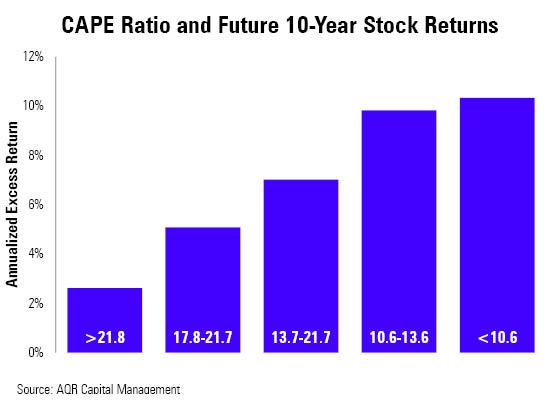

The article opens by acknowledging a strong argument against market-timing: Most of its appeal comes from bogus evidence. The familiar chart of future stock-market returns plotted against current cyclically adjusted price/earnings (CAPE) ratios illustrates the point. It looks to be highly predictive, as high CAPE ratios foretell future stock-market performance that barely beats cash, while low CAPE ratios portend excess returns of more than 10% per year.

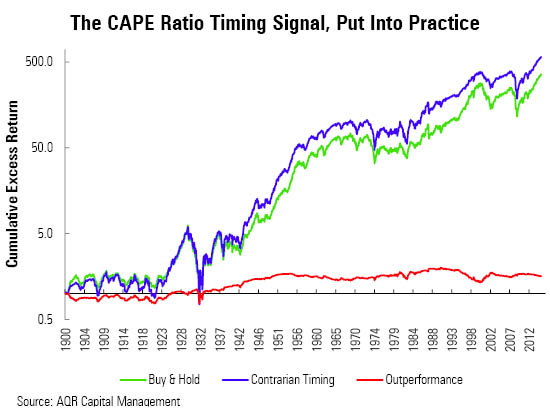

Unfortunately, the signal's success is faux. When the authors put the CAPE ratio to test, by devising a stock-timing strategy based on the past 115 years' worth of data, they found only a small advantage for the market-timing approach, as opposed to buying and holding. Worse, that edge came completely from the first half-century; since 1950, the market-timed portfolio did not generate a dime of extra return. Following the CAPE ratio--or any other stock-market valuation indicator--would have given no benefit to tax-sheltered accounts and would have significantly damaged taxable accounts.

The authors explain, "Put bluntly, Exhibit 1 cheats while Exhibit 2 doesn't. Hindsight is indeed 20/20. Too often we analyze historical opportunities with the benefit of hindsight, assuming that investors of the past knew more about the future than they could have. (Indeed, simply knowing about the Shiller P/E is a type of hindsight bias, as neither the CAPE nor even Shiller himself has been around this whole period.) … The non-cheating approach, as employed in the trading rule behind Exhibit 2, involves making forecasts using only data that was available to investors at the time of investing."

So far, so familiar. I spent my first decade at Morningstar reviewing presentations from fund managers that showed how asset-timing schemes that had been developed with the full benefit of hindsight would have benefited investors, had such schemes existed. I spent the next decade watching those funds fail.

The authors redeem market-timing by adding a second indicator of momentum. That they would supplement the long-term signal of the CAPE ratio with a shorter-term gauge is unsurprising; as any value investor knows, securities that are relatively cheap can stay that way--or even get cheaper--for many years to come. Specifically, the authors look at the past 12 months' change in stock prices, with higher performance indicating stronger momentum and thus a larger stock weighting.

The ideal buying opportunity for this two-pronged model therefore comes when stocks have low price ratios and the market has recently rallied. Conversely, the sell sign is strongest when stocks have high price ratios and the indexes are slumping.

The authors urge a similar approach for bonds, with real (that is, after inflation) bond yields substituting for the CAPE ratio as the measure of long-term valuation, and the same short-term trend indicator of 12-month performance.

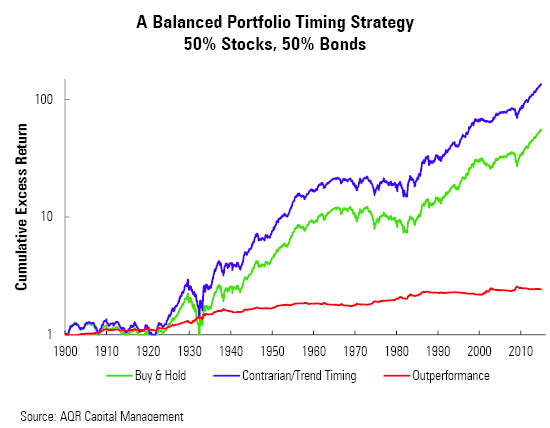

They tested this dual value/momentum timing approach on a portfolio of 50% stocks, 50% bonds. Unlike with the single-factor model, the market-timing portfolio doesn't stall in 1950. Instead, it builds on its lead over the next 65 years. For the full 115-year time period, the market-timing portfolio doubles the gains of the buy-and-hold portfolio. (On the graph, the advantage might appear to be smaller because the chart is scaled logarithmically.)

In this exercise, market-timing added about 50 basis points to annual performance after 1950--a useful amount, but not huge. On the other hand, every basis point counts.

The authors offer five suggestions for effective market-timing:

- Combine signals--one indicator will be insufficient.

- Include at least the two assets of stocks and bonds (and perhaps other assets).

- Have modest expectations.

- Act symmetrically (that is, use timing to overweight assets, as well as to lighten them).

- Don't be binary--don't turn assets completely on or off.

In summary, they write, market-timing can be one of many useful items on an investor's "shelf."

That works for me. Such a low-key scheme need not be implemented formally. It could be used casually, to hold off making stock or bond purchases if the long- and short-term indicators are unfavorable, or to invest spare cash should they flash green. That would be a safe, reasonable way to implement a form of market-timing. So yes, I concede the authors' (and Bob Desrochers') claim: It is possible to time assets without donning a red nose.

Finally, a bit of bad news: The authors' model currently likes neither stocks or bonds. Stocks fail both signals, having high price ratios and mediocre short-term momentum. For their part, bonds score respectably on momentum, but they are even more expensive than stocks on a relative basis, so they end up at almost the same place. The model suggests that investors be 14% underweight in stocks and 15% in bonds.

In other words, today might not be the best time to put that extra cash to work.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)