What the Market Is Telling Us About the Impact of a Potential Fed Rate Hike

The market isn't as panicked as many investors have been.

In the weeks leading up to the Fed’s meeting today, the bond market has increasingly priced in the expectation that the Fed would raise short-term interest rates. Still, slowing growth in China and troubling signs leave a bit of room for the possibility that the Fed might reconsider its plans.

Over the past few months, we’ve taken a look at the potential impact of a Fed rate hike on bond funds by examining rising-rate periods of the past and more recently at evaluating how some of our Morningstar Medalists fared during rising-rate periods. The past can only tell us so much, of course, given that no two interest-rate cycles are identical. Indeed, the global economic and political landscape has changed tremendously even since the Fed’s last rate hike cycle in 2005-06.

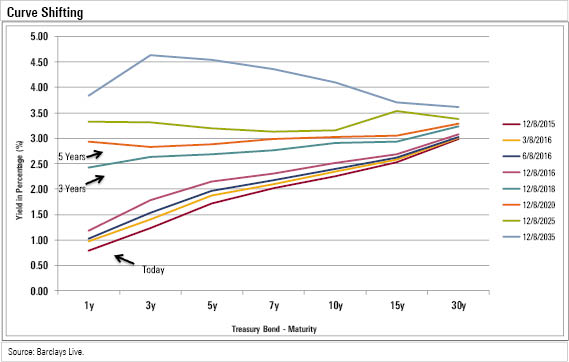

This time, we’ll look at what the markets are actually telling us about the possible impact of a Fed rate hike. Just about everyone in the financial industry has an opinion about where things are headed in the future. And even if many of them are way off, there can often be value in examining the collective expectations of a very large group. One way to do so is to look at so-called forward interest-rate curves. The graph below shows what bond prices were saying a few days ago about the market's expectations for yields across the maturity spectrum for different points in the future.

There are shortcomings to this approach. Forward rates are not known for their predictive accuracy. The idea of this exercise, however, isn't to try to zero in on exactly where rates are going but rather to take a look at the market's best guess for the future level of yields across the maturity spectrum and to use that information to estimate how badly bonds would be hurt if yields were to go up that amount--all at once.

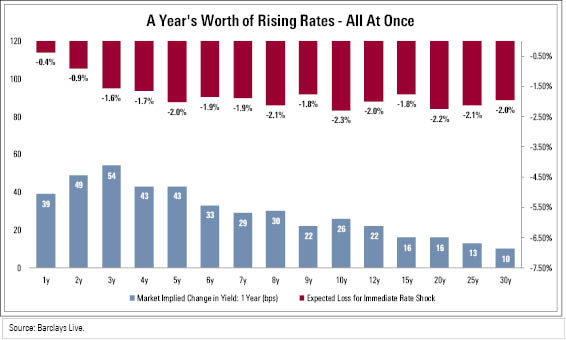

One way to do that is to take the duration of each bond we're looking at (in this case, 15 Treasury bonds maturing between one and 30 years from now) and use it to estimate each bond's loss given an expected change in interest rates.

The bars at the bottom of this chart represent the market's expectation of how much yields will change (in basis points, or one one-hundredth of a percentage point) from recent levels to one year in the future. The bars at the top represent how much you would expect each bond to lose if its yield changed that much all at once. So, for example, the market has been anticipating that the yield of a three-year Treasury note will rise 54 basis points over the next year, which, if that shift were to occur all at once, would imply a 1.6% loss of principal.

As you can see, the market's expectations for bond yields a year from now aren't exactly dramatic. On an absolute basis, a change of 54 basis points for the yield of a three-year Treasury note may look like a lot given that it only yielded about 1.2% a few days ago. But since the bond's maturity is so short, its duration is, too, clocking in around 2.9 years. When you put those two numbers together and assume that the bond's yield would shift immediately, you would expect the bond to lose 1.6% of its value.

The Greater Fear What if yields shoot up more than that? That's been the worry of investors and pundits ever since Congress approved a giant stimulus package after the financial crisis, and the anxiety has only increased with subsequent monetary stimulus packages, including the Fed's so-called quantitative-easing programs. In fact, one of the most ominous suggestions--particularly among those fearful that the U.S. dollar is in danger of dramatically losing its value--has been that the magnitude of those programs was so large and unprecedented that we're bound to be at the precipice of a long and painful stretch of inflation.

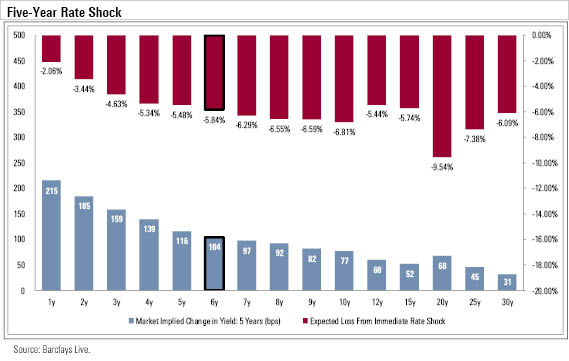

But, while the market's expectations for yields five years from now are certainly higher than those for one year, they're not the stuff of pandemonium.

We highlighted the six-year Treasury note because its duration of 5.6 years happens to be almost exactly the same as that of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index right now. That benchmark is a reasonable proxy for a core slice of the bond market and is used by nearly all intermediate-term bond funds designed to fill that role in investors' portfolios.

The chart shows that the market expects a six-year Treasury note to endure a 104-basis-point yield increase over the next five years. If you use that estimate and assume that the entire shift hits in one day, and then apply the bond's duration to estimate a price shift, you come up with an estimated loss of 5.8%.

We wouldn't expect every portfolio with a 5.6-year duration to perform exactly the same for a given shift in Treasury bond yields. A typical intermediate-term bond portfolio includes bonds of all types and across multiple maturities, making its duration an average of many different factors and thus harder to model. But on average, the aforementioned 5.8% loss projection should be a pretty good estimate of the interest-rate risk in a portfolio.

This is clearly a hypothetical exercise, and, even in a worst-case scenario, it is hard to imagine an environment where such a sharp increase in yields were to hit in such a short time period. Moreover, as yields rise, so, too, would the income generated by a bond portfolio with a consistent strategy, which would quickly start to offset losses. So, while we don't want to minimize the importance of a hypothetical 5.8% short-term price loss, it is a number that suggests many of the more blustery statements about interest-rate risk could be exaggerated.

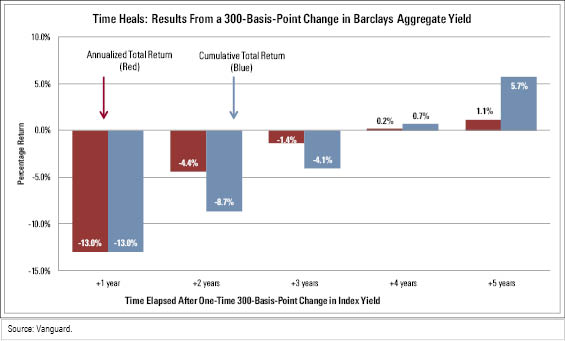

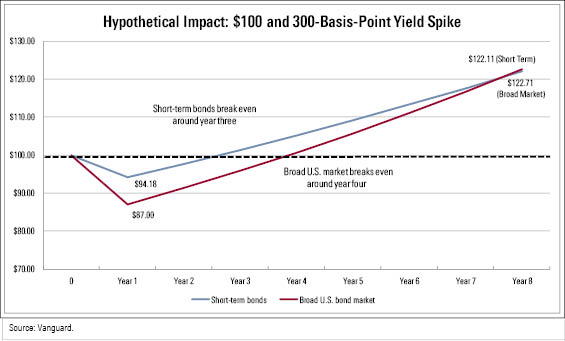

Approaching Armageddon Even so, it is fair to ask what would happen if things were much worse and how they would play out over time. Vanguard has done some work in the past to address those questions. And while the data itself is from a couple of years ago and addresses a shift in the broader market rather than the short-term rates directly controlled by the Fed, the implications are the same.

One of its hypothetical examples asks what would happen in the event of a 3-percentage-point jump in the yield of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, noting that such an occurrence would be rare in the extreme. Even then, however, the results were telling.

Vanguard's example referenced data from May 31, 2013, but the index's yield and duration were reasonably close to their levels of today. The Vanguard study also went a step further and modeled what would happen to an investor's returns if that 300-basis-point change were to happen all at once but yields were to stay stable thereafter. There's no question that the first couple of years would be painful, but the longer-term implications aren't nearly as bad as one might expect for such an extreme scenario. In part that's because, for an index or portfolio whose broad characteristics otherwise remain steady over time, the increase in market yields will eventually begin to offset the pain felt by the initial drop in principal.

Here's how the same 300-basis-point exercise looks in dollar terms for the Aggregate Index as well as a short-term government-bond index.

It would be folly to completely rule out a big interest-rate spike. But as we noted earlier, many observers have been banging the drum for investors to get out of bonds ever since Congress and the Fed began feeding stimulus into the economy following the 2008 crisis; witness the large outflows from core bond funds. Yet, we remain in the longest stretch of rock-bottom Fed-controlled short-term rates in history and still haven't seen any signs of runaway growth or inflation.

Meanwhile, most of the bond managers that Morningstar covers conflict with each other on some nuances but agree on the bigger picture. Most expect that the still-fragile global economy won't produce massive growth nor will it generate enough inflation here in the United States to warrant more than slow, measured changes to the Fed funds rate, which could easily take a couple of years to develop.

As we've suggested before, though, it is extremely difficult to anticipate market outcomes, even if and when the Fed does act. Whether investors believe the central bank is acting too quickly, too slowly, too much, or too little can make a tremendous difference. Moreover, both the Fed and the market are always factoring in changes in the economic landscape of the United States as well as those of countries whose fortunes are tightly tied to ours.

If there's one thing we can say with confidence, though, it is that investors should be very cautious about making sweeping changes to their portfolios out of fear. Investors who abandoned Treasury bonds in the years prior to the financial crisis were left without the single asset that proved most resilient during the carnage.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)