When Funds Get Bloated

Too much of a good thing.

A version of this article was published in the October 2015 issue of Morningstar FundInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of FundInvestor here.

Has asset growth altered your fund's strategy? Has it done so to the point where it starts to hurt performance?

These are the questions that the bloat ratio aims to answer. The bloat ratio is a figure I came up with years ago to dig into issues of liquidity and trading costs. The raw ingredients for bloat ratio are the fund's turnover ratio, the fund's top 25 holdings and the number of shares it holds, and the average daily trading volume for those holdings. First, divide the average daily trading volume by the number of shares owned by the fund. That tells us how many days' trading volume the fund owns. The bigger the number, the less liquid the position. If a fund owns, say, 10 days' trading volume of a stock, it might take months to get out without crushing the price. Then, we take the average of the fund's trading volume figures and multiply by the turnover ratio. (That 10 days' trading volume position might be manageable for a fund with 10% turnover, but the trading costs will likely be steep for one with 100% turnover.) That gives us the bloat ratio.

It has merit both for descriptive and predictive power. It helps you understand the fund's bloat relative to peers. In addition, changes in the bloat ratio can signal changes in strategy, including those brought on by asset bloat.

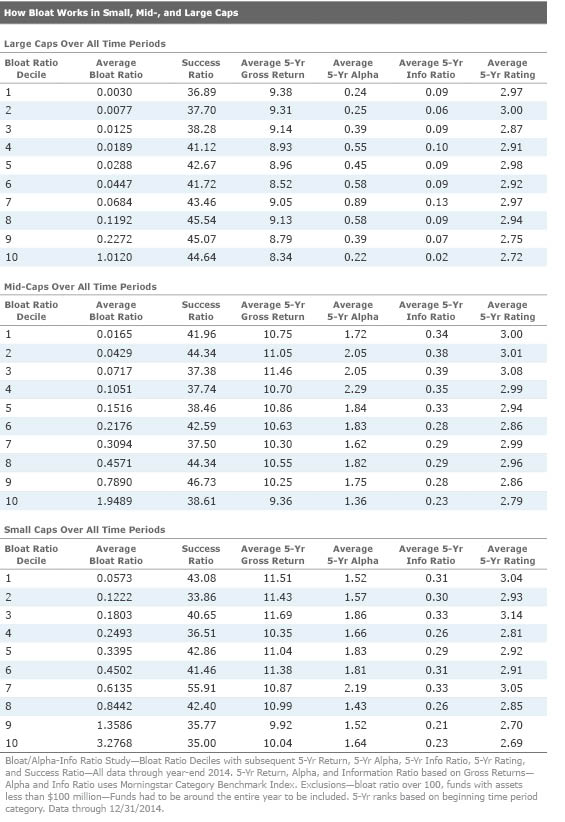

In order to test predictive power, I grouped funds by their bloat ratio and then tracked returns over the ensuing five years. I looked within large-cap U.S. funds, mid-cap U.S. funds, and small-cap U.S. funds. I backed out expense ratios for the test in order to isolate bloat. One positive effect of asset growth is that expense ratios usually fall, so I wanted to keep that out of the equation. I also excluded funds under $100 million, as they are less likely to survive and less likely to be considered by many investors.

I looked at funds over a number of rolling five-year periods in order to capture a variety of market environments. I then looked at the average of those periods to understand what was going on.

Small Caps Are the Most Bloat-Sensitive We grouped small-cap funds by decile, then looked at ensuing returns, success ratios, alphas, five-year Morningstar Ratings (or "star ratings"), and information ratios. Only the star rating is after expenses (as well as adjusted for risk and loads).

The pre-expense returns for the least-bloated decile were 11.51% annualized versus 10.04% for the most-bloated decile. The information ratio was 0.31% for the least-bloated decile versus 0.23% for the most-bloated. The least-bloated decile had a star rating of 3.04 versus 2.69 for the most-bloated. The success ratio for the smallest bloat decile was 43%, and for the bottom it was 35%. The success ratio tells you what percentage of the group survived and outperformed its peers. It is a way of preventing survivorship bias from creeping into the data.

For these measures, the bloat ratio would seem to have some useful predictive power, though I would not put it on par with the expense ratio.

It had less predictive power for alpha among small caps.

For mid-caps, the least-bloated decile slightly outperformed the most-bloated decile, but the impact was quite small. For large caps, no impact was apparent.

This makes sense as there is much less liquidity in small caps than in mid-caps and large caps. A fund would have to get enormous for bloat to be a big problem in large caps. More commonly, we see asset bloat become a modest handicap to which a manager may adjust by moving up in market cap and dialing down turnover. That can still be a negative, and you never want to see a manager alter his style to deal with asset bloat, but clearly the impact is generally small.

Biggest Increases in Bloat Ratio Let's look at some of the large changes in bloat ratio, beginning with those where it went up.

By far the largest boost came at

Even so, with $16 billion total assets under management, Ellenbogen has some real limits on the stocks he can buy and the speed with which he can trade them.

Biggest Decreases in Bloat Ratio

Janus Venture and Janus Triton are the flip side of Meade and Schaub going to Arrowpoint. The funds' replacement, Jonathan Coleman, likes his portfolios more diffuse than they do. Thus, Janus Venture fell from 4.8 to 1.6. Coleman has about 40 more names in his portfolios than his predecessors did. Janus finally got around to closing Triton now that it has more than $7 billion in assets.

The Least-Bloated Funds

Most of the Morningstar 500 funds have above-average bloat ratios because they have above-average asset bases. But there are some diffuse small-cap funds that might be worth a look.

Among mid-cap funds,

For a list of the open-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the closed-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the exchange-traded funds we cover, click here. For information on the Morningstar Analyst Ratings, click here.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)