The Costs of Active Management

Skills, expenses, and taxes.

Sources of Pain It's common knowledge that actively run stock funds tend to lag index funds.

But why? One possibility is that active managers collectively make poor investment choices. Another is that their investment decisions are satisfactory but are undermined by trading costs. Yet another is that active funds overcome the burden of their trading costs but not that of their official expense ratios (which do not include trading costs). Finally, there is the issue of taxes. How much damage, if any, does active management cause with taxes?

Let's look at core domestic-stock funds--the three investment categories of large-blend, large-growth, and large-value U.S. stock funds. Within each category, Vanguard offers the industry's largest and oldest index fund. Those three Vanguard funds are baselines, in that they represent what investors would have received from defaulting into the obvious index choice. The costs of active management can be determined by comparing those funds against the average active competitor.

Active Fund = Index Fund +/- Skill - Expense Difference - Tax Difference

To put the formula into words, an active fund delivers an index fund's performance, plus or minus the contribution of the manager's active decisions (that is, skills), minus the difference in the two funds' expenses, minus the difference in tax burdens. (In theory, an active fund could have a lower expense ratio or lower tax burden than an index fund, making those items positive, but in practice that rarely occurs.)

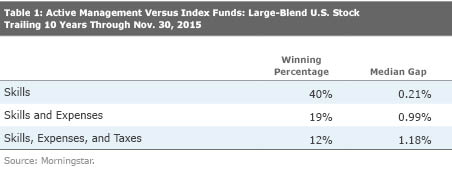

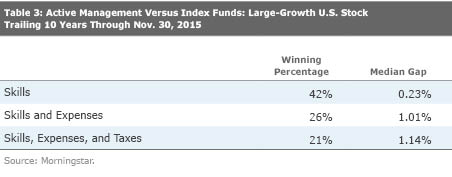

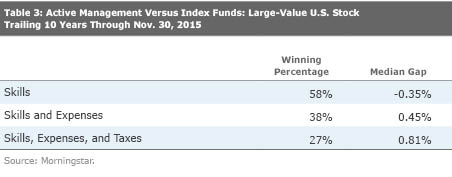

In the tables below, the Skills row measures how active funds fared against the relevant index funds on gross returns, that is, when both the active funds' and index funds' expense ratios were added back to their posted performances. The Skills and Expenses line shows what investors actually received (that is, after fund expenses) before taxes. Finally, the Skills, Expenses, and Taxes row includes the effect of federal taxes, assuming that the funds are bought entering the period, liquidated at the end, and that the investor paid the highest marginal tax rates.

As for the columns, Winning Percentage indicates the percentage of actively run funds that beat the comparison index fund, and Median Gap shows the distance between the performance of the median active fund and the index fund.

By the Numbers

(These figures flatter actively run funds, because by definition, sorting for funds that have trailing 10-year histories ignores funds that existed at some point during the past decade but did not survive. It's difficult to conduct this particular test while accounting for dead funds. Thus, the interpretation of this test should be, "The costs of active management, assuming that the investor selects a fund that survives the next 10 years."

Such an assumption is fairly reasonable for the major fund families, such as Vanguard, Fidelity, or American Funds, which rarely kill off their core U.S. stock funds. It's not so reasonable for some of the industry's lesser players, which are lamentably prone to throwing new funds against a wall and seeing what sticks.)

Roughly speaking, the typical active core stock fund--at least for those families that tend to keep their funds alive--performs pretty much in line with the indexes after trading costs, but before paying their official expense ratios. One sometimes encounters ominous rumbles about the large trading costs that active mutual fund managers must pay, which dooms them to underperformance, but these tables do not support that argument. On the whole, the portfolios of the active funds have been fully competitive.

Expense ratios have been the big problem. To the extent that active management can outleg the index funds on a gross basis, as with the large-value funds, the margin of victory is small. The 1% expense ratio that is carried by most actively run large-company funds is far too large to sustain such a triumph. As a group, active funds must become much cheaper if they are to be competitive on a pretax basis.

The task is tougher yet after taxes. While the extra tax burden caused by the actively run funds is a smaller problem than is their expense ratios, it is nonetheless an additional impediment for taxable accounts. With only 12%-27% of active funds beating index funds after taxes, and the active funds facing the additional uncertainty of possible liquidation/merger (an event that rarely occurs with index funds), the odds are long indeed for taxable investors who hold active U.S. stock funds.

The Upshot It's the fashion these days to cite idiosyncratic, concentrated funds as the best competitors for index funds. The notion is that if an investor is to pay a premium for active management, it's best to get the most active of that breed. That's one approach. Another, however, would be to acknowledge the math of active management and to seek to limit the damage caused by expenses and taxes. Run the active funds cheaply (ideally, very cheaply), trade infrequently, and offset capital gains with losses if reasonably possible. The artistic path is a viable road--but so is the miser's.

Dinged! Sure enough, Tuesday's column in defense of closet-index funds had its detractors.

Politely, though, the criticisms seem to miss the point. My support of closet indexing was decidedly left-handed, as--using this column's math--I stated that, as a group, closet-index funds would almost certainly trail actual index funds, without providing offsetting benefits. But that is true of other flavors of actively run funds, too. So why single out one type of active fund for special criticism? That is my question.

And no, this columnist does not support "high fee active management"! I blanched when I read that.

More Is Less

Per yesterday's

Wall Street Journal

,

That's a thumbs down on management if I've ever seen one.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)