Fighting Inflation in Retirement

The current formula driving Social Security's cost-of-living adjustment is out of whack, says contributor Mark Miller. Here's what seniors can do to keep up.

The news that Social Security beneficiaries won't receive an inflation adjustment next year has renewed debate about how we measure the cost of living for seniors.

A strong case can be made that the current formula driving Social Security's cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) is out of whack. The COLA is tied to the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which gauges a market basket of goods and services of working people--who tend to be younger and spend less on healthcare than seniors.

The inflation rate experienced by seniors often runs higher than the CPI-W reflects. That has implications for federal policy--many advocates for seniors have pushed for adoption of the CPI-E, an experimental measure created by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to measure the inflation affecting elderly Americans. There's been a countervailing push to use the "chained CPI" which would result in even smaller COLAs that those currently awarded.

But the higher elderly inflation rate also has implications for portfolio management and pocketbook management for retirees. Retirees are especially vulnerable because they don't have the capacity to counter inflation by seeking higher wages, and returns on low-risk fixed-income investments aren't getting the job done in a time of near-zero interest rates.

The Right Yardstick? From 1985 to 2014, the CPI-W ran 6.5% behind the CPI-E, according to research by J.P. Morgan Asset Management. A slowdown in healthcare cost inflation has, however, led the two indexes to converge a bit during recent years. But if medical inflation does take off, the argument for using the CPI-E is likely to heat up again.

And health inflation does appear to be returning to its historical norm--about 7% annually. Renewed health inflation fueled the controversy over the flat 2016 Social Security COLA because some Medicare beneficiaries--those not "held harmless"--could have faced a huge 52% hike in Part B premiums. (That didn't happen: If you're not on Social Security but enrolled in Medicare, you'll be paying $118.80 per month, plus a monthly $3.00 surcharge, for a total of $121.80. The Part B deductible will be $166.00 for all beneficiaries, up from $147.00.)

And Medicare's trustees forecast that the Part B premium will reach $140.00 in 2020, and $174.00 in 2024.

Furthermore, premiums for the 10 most popular Medicare Part D plans are jumping an average of 8% next year, and five of the most popular plans will see double-digit increases. That's a big change from recent years--average premiums for the top 10 plans have been flat or down a bit in each of the past four years.

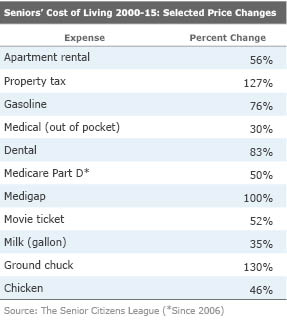

Inflation's impact on seniors isn't limited to healthcare. Social Security beneficiaries have lost 22% of their buying power since 2000, according to a study by the Senior Citizens League (TSCL). The study examined prices of key consumer goods and services typically bought by seniors from 2000 to January 2015. Of 34 items measured, 22 exceeded the amount of increase in the COLA over the same period (see chart below showing selected items from the study). The TSCL survey found that the COLA has increased benefits 43% since 2000, while typical senior expenses have jumped 74%.

Numbers like these underscore why it would be a bad idea to revise the COLA formula to award smaller increases--an idea that has been pushed by some Republican legislators and presidential candidates, and was embraced (briefly) by President Obama. This would be done by adopting a "chained CPI." This alternate measure is based on an economic theory that the CPI-W overstates inflation because it fails to account for the substitution that consumers make when the price of a particular product or service gets too expensive.

The chained index attempts to reflect these substitutions. The theory is that a spike in gasoline prices will prompt consumers to spend less on fuel, perhaps more on food, and so on.

The initial impact of a chained CPI looks small--the Social Security Administration estimates it would reduce the COLAs by 0.3% annually. But with compounding, its effects would grow over time. With an average monthly Social Security retirement benefit this year of just $1,270, even small cuts would be painful for many seniors.

Also worth noting: low or zero COLAs don't only cut into benefits for current enrollees, they also cut into future benefits for people who are eligible for benefits (ages 62 to 70) but haven't yet filed. When you delay taking benefits until a later age--say, full retirement age (66)--you get full benefits increased by the COLAs awarded for the intervening years.

Planning for Inflation What can you do to hedge against the negative effects of future inflation in retirement?

Work longer. Additional years of work can fund living expenses while you delay your Social Security filing; that not only boosts your monthly benefits by approximately 8% when you do claim, but COLAs awarded during the interim (from age 62) will be added to your benefit. And, the dollar amount of COLAs will be larger down the road, since they'll be calculated against a larger benefit amount. Working longer also means fewer years of drawing down your retirement savings, and additional years of contributing to those accounts.

Stick with stocks. The prospect of higher retiree inflation also argues for keeping at least some portion of your portfolio in equities well into retirement.

Rob Arnott, CEO of Research Affiliates, has argued that target-date funds take risk and return off the table too quickly for pre-retirees and that they are forcing millions of retirement investors into negative-return fixed-income vehicles, mainly Treasuries.

Wade Pfau and Michael Kitces think the risk of portfolio failure in retirement actually is lower for investors who start retirement with a relatively low equity allocation and then increase stock allocations to 70% or 80% over time. (Pfau is a professor of retirement income at the American College; Kitces is director of research at Pinnacle Advisory Group.)

Larry Rosenthal, president of Rosenthal Wealth Management Group, agrees."Putting your money only in secure investments is a good way to go broke over time, because you lose purchasing power," he says. "Just because you reach retirement age, that doesn't mean you won't need money at 75, 85, or 95--you'll need it to cover inflation and taxes down the road. So, you need to turn your portfolio into income and grow it at the same time."

Rosenthal offers the example of a client who needs $7,000 in monthly aftertax income, who receives $4,000 combined from Social Security and a pension. If the client has a $1 million investment portfolio, he needs a 3.6% return to generate the $36,000 that would plug that $3,000 monthly income gap. "So, you would want to make sure some of the money is in a growth and income mutual fund--perhaps 70% stocks and 30% bonds. It's designed to grow and kick out income. The rest of the portfolio would go into a conventional 60-40 stock-and-bond allocation."

Be a smart healthcare consumer. Learning to be an educated consumer of health insurance can help. The Medicare program has plenty of moving parts, and you can benefit by making smart buying decisions. This starts with the basic question of enrolling at the right time to avoid costly penalties and continues with a decision of whether to enroll in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage, the all-in-one managed-care alternative. Medicare Advantage usually doesn't charge separate prescription-drug premiums and doesn't require a Medigap plan. (In fact, Advantage participants can't buy them.) The trade-off is flexibility, since enrollees must use in-plan healthcare providers.

Also, reshop prescription-drug coverage regularly, since plans' terms of coverage for drugs often change from year to year--and so might your medication needs. One research study found that almost one quarter of Part D enrollees could save at least $500 annually by picking a cheaper plan better suited to their drug needs.

Mark Miller is a retirement columnist and author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work, and Living. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XLSY65MOPVF3FIKU6E2FHF4GXE.png)