Will Rising Rates Hobble Highly Rated Core Bond Funds?

History and market expectations argue that fears of their impending doom are greatly exaggerated.

If the Federal Open Market Committee raises the Fed-funds rate when it meets in mid-December 2015, it will be the first time it has done so since June 2006. Investors and pundits have been anticipating--and wringing their hands--about a potential rate hike since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, but it is the longest stretch in history that the so-called Fed policy rate has gone without a change.

There's no way to surely predict what the FOMC will do in December, but futures markets put the probability of a hike at nearly 75% in late November, up from less than 50% a month earlier. Nor can one predict with any certainty how markets will react if a December rate hike is followed by more over the months and years that follow, which appears likely. The latter no doubt worries many investors, along with how core bond funds in their portfolios will react.

We're Not Flying Entirely Blind We have the advantage of some historical examples to look at, though, making it possible to examine how some of Morningstar's favorite core bond funds with Morningstar Analyst Ratings of Bronze, Silver, or Gold have fared during past rising Fed-funds rate cycles.

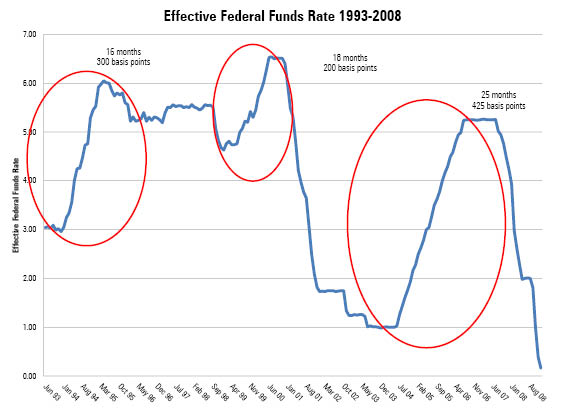

Things actually played out better than you might think. Take the Fed rate hikes that began in early 1994. The Effective Fed Funds Rate chart (above) is an empirical measure of the Fed-funds rate, so the amounts and timing differ a bit from the Fed’s so-called targeted rates, but there were a total of seven hikes of different amounts that brought the target Fed-funds rate up by a total of 300 basis points in 12 months.

For those who remember the period, it likely conjures recollections of disasters such as the implosion of Orange County, California's investment portfolio or the 28% losses incurred by individual investors in Piper Jaffray's Institutional Government Income Portfolio (which was actually sold as a conservative investment to small investors despite having institutional in its name).

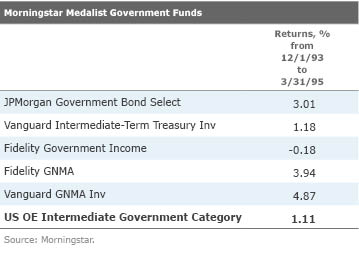

Those were outliers, though, driven by the portfolios’ reckless use of extremely rate-sensitive mortgage derivatives. On the whole, though, the intermediate-term government-bond Morningstar Category--at $75 billion, it was the largest fixed-income category in 1993--was much more plain-vanilla. As such, it didn’t experience anything nearly as bad, and four of the five Morningstar Medalists in the category performed better than the average. The one exception,

There was short-term pain over the period of the Fed’s hikes, but it didn’t take long for investors to recoup those losses. And, if anything, that helps support the notion that quick, sharp, short-term rate hikes, in and of themselves, aren’t necessarily the disaster for longer-maturity bonds that they might appear to be.

This Isn't Your Father's Bond Market Bond markets have also evolved a great deal since the mid-1990s, and investors have had a very different focus in recent years. At $39 billion in 1993, the intermediate-term bond category now boasts more than $1 trillion, while the intermediate-term government group is roughly one tenth that size, having grown little over the past 22 years.

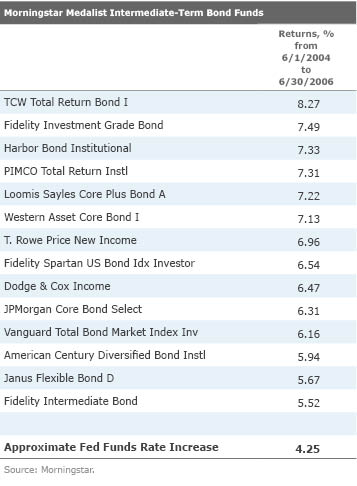

As the table above suggests, funds in the intermediate-term bond category survived the last, fairly severe wave of interest-rate hikes without knuckling under, and Morningstar Medalists did particularly well. In fact, from June 2004 through June 2006, the FOMC raised the Fed-funds rate 17 times, for a total of 425 basis points, and the average intermediate-term bond fund still managed a total return of more than 5.6%.

If anything, the maximum drawdown data for the intermediate-term bond category, and even its Morningstar Medalists, illustrate that, when you include the three major rising-rate cycles since 1993, the financial crisis was a much bigger problem for most of them.

Is The Past Really Prologue? We'll be addressing some broader questions around the possibility of a December Fed hike as the next FOMC meeting gets closer, but an easy criticism of focusing too much on a fund's performance during the prior cycle might be that the next hiking cycle could well be different. In particular, a nasty spike in inflation, rapid, large Fed-funds hikes, or a sharper sell-off in long-dated bonds could all spell trouble.

But there is some additional reason for optimism--the relatively muted expectations of the Treasury market and many fund managers for future levels of inflation, and the pacing and magnitude of rate hikes that might follow in the footsteps of a December shift.

The most common refrain Morningstar analysts have been hearing is an expectation of gradual hikes of 25 basis points at a time, most likely stretched over many months between hikes. Based on the market’s signals right now, it’s hard to envision anything much more than that.

For one, prices for Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities suggest expectations for a modest 1.3%-per-year level of inflation over the next five years (when their yields are compared with those of conventional Treasuries) and only a slightly higher 1.6% over the next 10. Even if those numbers turn out to be low--as some fund managers expect--it is difficult to envision them coming close to the 3.1% pace of inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) observed, on average, from 2004 through 2006.

The market’s expectations for increases in the 10-year Treasury yields are muted as well, with forward Treasury bond curves predicting the 10-year note to yield 30 basis points more a year from now than it does today, 50 basis points more in two years, and 70 basis points more in three years.

Those numbers aren’t negligible, but, spread over enough time, that level of change in the yield for a 10-year Treasury bond implies a much less bumpy ride than many investors seem to fear.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1b991ddd-b85f-490e-8687-e60e3f136800.jpg)