Is Being Good the Secret to Being Great?

Not, it seems, with stock mutual funds.

The Road to Heaven A quarter-century ago, hedge fund manager Howard Marks argued that investment managers are better off being consistently good than trying to be occasionally great. This claim has recently come to the forefront, as AQR's vocal and visible leader, Cliff Asness, has been citing it admiringly.

Wrote Marks, "I feel strongly that attempting to achieve a superior long term record by stringing together a run of top-decile years is unlikely to succeed. Rather, striving to do a little better than average each year--and having the discipline to have highly superior results in bad times … is more likely to work."

Marks told of a pension fund that enjoyed outstanding performance from its stock portfolio, scoring in the fourth percentile over a 14-year time period against its competitors. During that period, the fund's stocks never finished higher in any calendar year than the 27th percentile, nor lower than the 47th. Quite literally, it spent every year in the second quartile. As Marks put it, that fund achieved greatness by being "just a little bit above average on a consistent basis."

The argument for goodness, rather than greatness, made a lot of sense to me. It's the formula espoused by American Funds, which is sorely out of fashion but which nonetheless has beaten the relevant indexes--and the vast majority of its competitors--with every one of its stock funds over the past 15 years. It's also how index funds succeed (minus the part about thriving during the bad times), as their cost advantages accumulate modestly but reliably. As the time period lengthens, index funds' relative performance strengthens, as was the case with Marks' pension funds.

But it doesn't seem to describe how stock mutual funds operate.

The Data's Tale Morningstar's Jeff Ptak--to whom this column owns a great debt--compiled the calendar-year return percentiles for all existing stock funds (diversified domestic, international, and sector, including index funds). His was a quick study, in that it used current category classifications, rather than attempt to track down if and when a fund changed categories and then to compute its percentile ranking given the category it had at that time. However, that shortcut should not bias the results. The effect is modest, plus I can think of no reason category changes should tilt the findings in any particular direction.

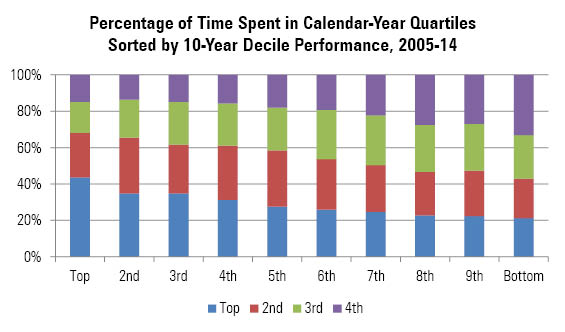

These were the results, for the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2014.

- Source: Morningstar

Funds that scored top-decile returns over the full decade--a reasonable definition of greatness, although one could perhaps argue that some of those funds merely achieved "very goodness"--did not do so, on average, by posting a string of second-quartile returns, in the fashion of Marks' pension fund or an S&P 500 fund. They got there by racking up a whole lot of top-quartile showings.

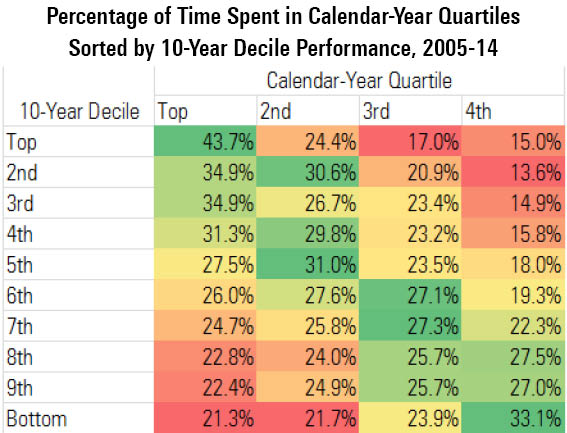

This table shows the data in more detail.

- Source: Morningstar

The top-decile funds landed in the highest quartile for calendar-year returns 43.7% of the time, with the next two deciles each registering significantly fewer strong calendar-year performances, at 34.9%. In contrast, the second-quartile returns for the top-decile funds were distinctly ordinary, at 24.4%. The next five deciles of funds all surpassed that figure. Nor did the top-decile funds have the fewest amount of bottom-quartile showings. They did well, scoring 15%, but on that measure they trailed the second- and third-best deciles.

The road to being great for stock mutual funds was not goodness, but rather greatness.

Ptak supplied not only the data, but also what I believe to be the correct take on the matter. Jeff writes,

"Great funds probably aren't good. Rather, they're intermittently amazing and horrendous. Streaky. Hard to stick with. Demanding. That would seem to match findings that the long-term standouts have often plumbed their category's depths, owning securities that others neglect. Bad stuff routinely happens to great funds. Being merely good isn't enough. You have to be bad … awful at times … and stick with it … and then maybe you'll be great."

I would add that the bad years should mostly come from trailing the bull rather than lagging the bear, because the task of overcoming extremely steep losses is daunting (that is, it takes a 100% gain to break even after a 50% decline). Also, while the great funds must be bad at times, perhaps even awful, those occasions should still occur less frequently than with other funds. After all, the study's top-decile funds landed in the bottom quartile in only 15% of years, as opposed to chance's 25%.

Hedging Time for the caveats. There are several.

First, splitting calendar years by quartiles is but one way of testing the subject. It's the ideal way to see whether there are many stock mutual fund versions of Marks' pension fund (there aren't), but it's not helpful for testing propositions such as: the best long-term funds are those that sometimes post very good calendar-year returns but rarely land in the top 5%. It's possible, although I think unlikely, that using other cutoffs would yield another conclusion.

Second, stocks are but one variety of mutual fund. I'm not sure that balanced or bond funds operate in the same fashion. In particular, bond funds have limited opportunities to overcome big deficits. At the least, fixed-income managers who hope to be great must avoid trailing sharply during the downturns.

Third, Marks wrote of hedge funds. The math of hedge funds differs from that of stock mutual funds, because hedge funds can and do go to zero. There's no coming back from that. With leveraged investments, avoiding disaster is paramount--far more than with mutual funds. Marks' theory does not seem to apply to stock mutual funds, but it very well might to his marketplace.

Finally, as Ptak stated, greatness isn't for everybody. It's easier to own a steady-Eddie than to hold a fund that can look terrible. The popularity of index funds owes largely to their comfort. They don't ever trail, not on a relative basis. On paper, goodness is not the typical path to greatness. In reality, though, it might be the road most investors must seek, if they are to avoid making bad decisions during tough times. And there's nothing wrong with that. Sometimes, practical considerations are more important than what the data studies suggest.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)