Rethinking Commodities

The biggest return-driver for commodity futures is market structure, not fundamentals or spot prices.

The article was published in the August issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of ETFInvestor here.

The holy grail of portfolio diversification: an asset class that provides long-term risk-adjusted returns similar to equities but is negatively correlated with the returns of stocks and bonds. That is what professors Gary Gorton and Geert Rouwenhorst (hereafter G&R) appeared to have identified in their seminal study, "Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures"1.

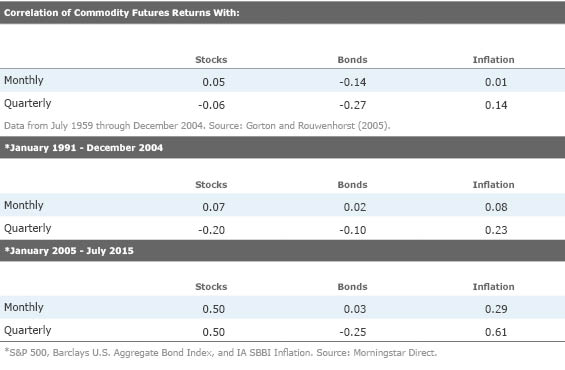

The paper looked at the period from July 1959 through December 2004 and concluded that the risk premium earned from investing in a broadly diversified basket of fully collateralized commodity futures is very similar to the historical equity risk premium. Moreover, the authors found that the volatility of commodity futures (as measured by standard deviation) was less than that of stocks. According to the study, not only were these superior risk-adjusted returns negatively correlated with stocks and bonds, but they were also positively correlated with unexpected inflation.

Unfortunately, what seemed too good to be true at the time might have turned out to be exactly that. A decade has passed since the study was released and sent waves through the investment industry. This gives us fertile ground to examine the subsequent performance of commodity futures in the years following the persuasive research paper. As it turns out, since the research was published, commodity futures have behaved a bit differently from the period studied.

There are a few key points worth highlighting that could help explain why the results of the study haven’t persisted post-publication. First, commodity futures were predominantly in backwardation (futures prices were lower than spot prices) during the time period studied. Therefore, the roll-yield component of the commodity futures’ returns provided a fairly consistent tailwind. Second, using three-month T-bills as a proxy, the risk-free rate during the period studied was much higher than it has been recently. This, of course, had major implications for collateral returns. In the period from July 1959 through December 2004, the three-month T-bill rate averaged 5.6% and rose as high as 16.3% in the early 1980s. Since the study was released, the average rate on three-month T-bills has been 1.34%. For further context, today the rate is 0.02% and has averaged 0.06% over the past five years.

Remember, the returns of commodity futures are composed of three parts: (1) changes in the spot price, (2) roll yield, and (3) returns on the collateral securing the futures contract. Though many who allocate a portion of their portfolio to commodity futures may expect that changes in the spot price are the most important driver, this has not been the case historically.

In fact, collateral returns have been the largest return component, followed by roll yield. Spot prices have actually been a drag on overall returns historically. In a 2008 study2, Vanguard examined the sources of the returns of the S&P GSCI from 1983 through Sept. 30, 2008, and found that the collateral return accounted for 6.4 percentage points of the benchmark's 7.1% annualized return during this period. The roll yield accounted for 3.3 percentage points, while spot returns actually detracted 2.6 percentage points annually (6.4% + 3.3% + 2.6% = 7.1%). Understanding the underlying components of commodity futures' returns--and their impact on performance--is critical for making an informed decision on whether or not to make (or keep) an allocation to the asset class.

Past to Present—Fundamental Differences Since the mid-2000s, commodity markets have predominantly been in a state of contango. But for the 45-year period that G&R researched for its study, commodity futures markets were consistently backwardated.

Based on Keynes' theory of normal backwardation3, it was reasonable to assume that the roll yield would continue to be an important contributor to total returns. Given that foreseeable trends (such as seasonality) are taken into account in futures prices, expected movements in the spot price should not be relied upon as a source of return to an investor in futures. As G&R noted, unexpected deviations from the expected futures spot price are by definition unpredictable and should balance out to zero over time (a positive expected return here would assume consistently successful market-timing).

Therefore, G&R determined that the expected return for commodity futures boiled down to what they called the risk premium. If the current futures price is below the expected futures spot price (backwardation), the buyer of the futures contract, on average, will earn a risk premium. On the other hand, if the futures price is above the expected future spot price (contango), then the risk premium is earned by the seller of a futures contract.

The theory of normal backwardation is predicated on the assumption that producers of commodities would seek to hedge the price risk of unexpected deviations between futures and spot prices. So in a sense, a producer selling futures to lock in future prices is obtaining a form of insurance against price risk. The insurance is provided by speculators who buy the futures and, in theory, demand that the futures price be below the current spot price in order for them to receive a risk premium for providing insurance to the producer. It’s critical to point out that another implicit assumption of the normal backwardation theory is that the number of producers requiring hedging outweighs the number of speculators in the market.

Unintended (and Largely Unexpected) Consequences of ETF Democratization? The advent of commodity exchange-traded products expanded financial investment in commodities from the few foundations and pensions that invested in the early futures indexes to an enormous pool of individual and institutional investors worldwide. This may have turned Keynes' theory of normal backwardation on its head, as speculators flooded the market in the mid-2000s, around the time that G&R published their influential research, and following a multiyear bull market for commodities (remember when China couldn't get enough?).

In the not-too-distant past, portfolio managers and individuals used to deal mainly in equities and bonds. An entirely separate set of farmers, energy producers, and mercantile-exchange arbitragers dominated the commodities markets. By the mid-2000s, many more investors began to engage in commodity investment/speculation. In fact, during this period of exceptional growth, the monthly financial activity in the commodity space often considerably outweighed the value of physical production. It appears that this influx may have had significant implications for the returns on those investments.

Consider that at the end of 2005, there was less than $5 billion invested in U.S.-listed commodity ETPs. About five years later, after a period of exponential growth, assets in commodity ETPs topped out around $125 billion. By this time, investors started to learn about terms like contango and backwardation, realizing that they needed to adjust their expectations. Since topping out in August 2011, commodity ETP assets have been in decline thanks to negative returns and sharp redemptions. Investors have yanked more than $22 billion out of commodity ETPs over this period.

Based on the available data, a reasonable hypothesis would be that financial interest grew too large relative to the physical market because of commodity index investors, creating excessive long-only demand that can only invest in futures contracts. This demand acts to push up the prices of futures contracts relative to their expected value, leading to a state of persistent and extreme contango.

If the same investors who were buying futures were instead buying physical commodities, we would have seen spot prices skyrocket as limited supplies were hoarded and stored. Instead, because futures contracts are habitually sold before expiration and the proceeds invested in the next contract, we witness futures prices that perpetually exceed the combined spot price and cost of carry.

Basic economics would tell us that arbitragers should step in to store the physical commodity and take the short side of the trade. Storage facilities are in limited supply, however, and many of their rates are capped by government regulation. Hence, we’ve witnessed oddities like oil tankers, normally used for shipment, sitting idle in ports to act as storage facilities. Once financial investment outstrips the available inventories and storage capacity, arbitragers can no longer perfectly hedge out short positions in the futures contracts, allowing long-only pressures to take over and push prices above what the market fundamentals would predict.

Adjusting Expectations Given the meaningful shift that has occurred in the futures market for commodities in recent years, it may be a good idea to reevaluate the case for commodities as a long-term investment. It's no secret that commodities have had a rough stretch over the past few years. Is there still a potential diversification benefit to adding commodity futures to a portfolio? Updated correlation data suggest that commodities may not be that useful as portfolio diversifiers. Along with the correlation figures presented by G&R, the first table below also shows correlations for the 10-year periods before and after the study was released.

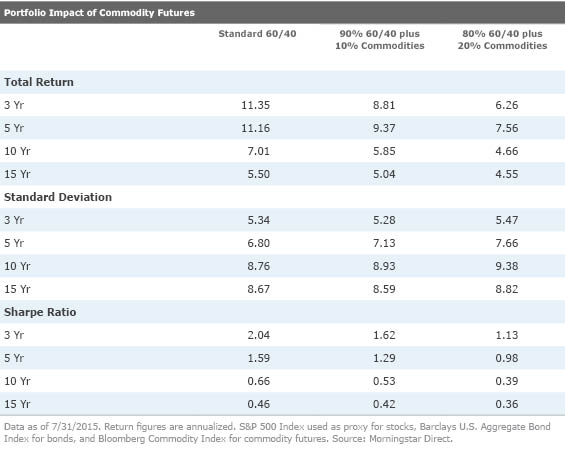

To gauge portfolio impact, I’ve used a hypothetical 60/40 portfolio as a baseline, comparing it against similar portfolios that include a stake in commodity futures. The results speak for themselves: Over the past 15 years, an allocation to commodities has generally resulted in lower returns and greater risk.

Whereas G&R’s influential academic research was based on a period characterized by positive roll yields and high collateral returns, the situation today is much different. Roll yields have turned sharply negative in recent years, and collateral returns are basically nil thanks to near-zero interest rates. Further, rising correlations over the past several years have damped the potential diversification benefits. As a result, barring a return to a persistent state of "normal backwardation," commodity futures may not be as attractive an asset class as it was once thought to be.

1 Gorton, G., & Rouwenhorst, K.G. 2006. "Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures." Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 62, No. 2, P. 47. 2 Phillips, C.B. 2008. "Commodities: The Building Blocks of Forward Returns." (Valley Forge, PA.: The Vanguard Group) 3 Keynes, J.M. 1930. "A Treatise on Money," Vol. 2. (London: Macmillan & Co.)

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc.'s Investment Management division licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-25-2023/t_f3a19a3382db4855b642d8e3207aba10_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)