An In-Depth Look at the Perplexing IVA Saga

IVA had an auspicious launch, an unusual life, and a startling end.

Editor's note: IVA co-founder Charles de Vaulx died on April 26, 2021, after this story originally published.

On March 10, 2021, International Value Advisers, or IVA, quietly submitted a shocking document to the SEC. There was no accompanying press release or letter to shareholders--just a terse announcement that the firm planned to liquidate its two mutual funds in short order. To prepare, both strategies would immediately start selling all the holdings in their portfolios, so that they’d only own cash and cash-like instruments until the liquidation date--which was only a month away. No reason was given.

That wasn’t all. The document stated that after the funds were liquidated, IVA itself would close down.

A day or two later, most of the firm’s personnel, including all but one of its seven analysts, had disappeared from the IVA website. No further information was provided.

To call these developments unusual would be a vast understatement.

Numerous questions arise. Why did IVA decide to liquidate the funds, and the firm, rather than trying to cut costs and keep going, or looking for a buyer? What brought IVA to the point that it even had to consider these options? Why do it so quickly and why was there no explanation? Is this firm’s demise a portent for other value-oriented managers that have been battling the market’s headwinds for many years?

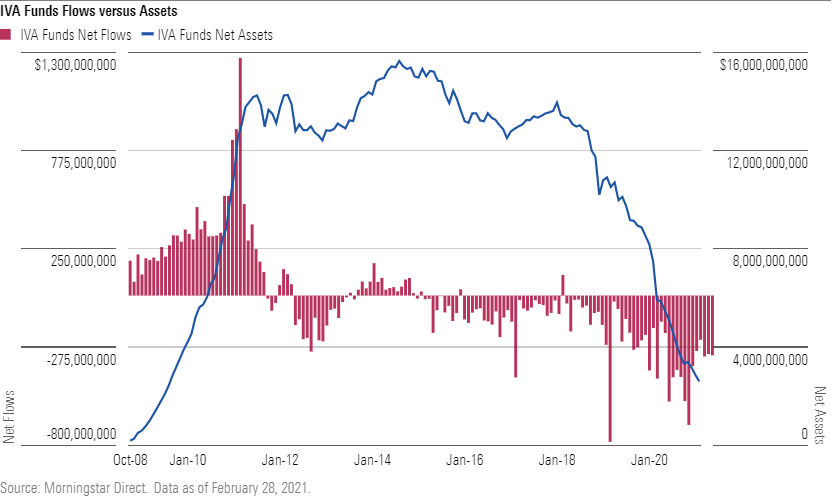

Putting the Events in Context

Asset-management firms occasionally liquidate funds, but much more often, when a firm decides a fund is no longer worth the trouble--typically owing to weak performance, difficulty attracting assets, or both--it merges the offering into a larger, more successful fund in its lineup. Full liquidations are rare and tend to happen only to funds with very small asset bases. But IVA Worldwide (known as IVA Global in Europe) and IVA International, though not behemoths, were not small. Despite heavy withdrawals in recent years, IVA Worldwide still had $1.9 billion in assets in the mutual fund alone at the end of February 2021, while IVA International had $500 million, and though the total assets in separate accounts may have dwindled, there likely were some assets there as well.

Moreover, fund shops that are struggling for whatever reason typically don’t liquidate if they still have a decent amount of assets; they put themselves up for sale and are usually snapped up by someone. That’s not to say it’s never happened. But it’s very rare, and likely to occur only in dire circumstances such as a public scandal or an unmanageable debt load putting the future of the firm in immediate doubt and scaring away prospective buyers. Neither was the case with IVA.

Exhibit 1

A Distinguished Pedigree

The story begins with Jean-Marie Eveillard. Running a go-anywhere, buy-just-about-anything fund called SoGen International (meaning global), he became a well-known value investor in the 1980s and 1990s. Performance was strong, and his French accent and elegant persona didn’t hurt. In the mid-1990s he hired Charles de Vaulx, a young French national, as an analyst. Eventually de Vaulx became comanager, and when Eveillard retired, de Vaulx took over as manager of the fund, which had changed its name to First Eagle Global SGENX, along with First Eagle Overseas SGOVX and other accounts.

But by then the fund firm had a new owner, and after ownership brought in private-equity investor TA Associates, de Vaulx and the new bosses had a falling out. In spring 2007 he abruptly left the firm. Not long afterward, he and a substantial group of colleagues from First Eagle created IVA, starting with institutional accounts and then launching two mutual funds that followed the strict value approach they’d honed at First Eagle. De Vaulx and comanager Chuck de Lardemelle, who’d been his colleague at First Eagle for about 10 years, didn’t want to build a big fund shop with an extensive lineup; they just wanted to offer reliable, risk-averse value funds that shareholders could hold for the long run.

Although the fund’s costs were no bargain, in most respects the new firm was shareholder-friendly. It committed to close the funds to new investors at a fairly modest level--something that First Eagle had not done, to de Vaulx’s dismay--and IVA followed through when assets hit that mark. An “owners’ manual” on the website laid out the IVA approach, explaining its intent to preserve capital even in downturns, not simply beat a benchmark. The managers held a conference call each year in which they offered their take on the markets and the funds and fielded questions from shareholders.

The managers’ timing, though, could have short-circuited their plans at the start. The IVA funds launched Oct. 1, 2008, in the teeth of the worst financial meltdown since the Great Depression. But that was precisely the time when shell-shocked investors were looking for a cautious, value-oriented offering run by experienced managers with a track record. Under such unusual conditions, IVA had no trouble attracting assets.

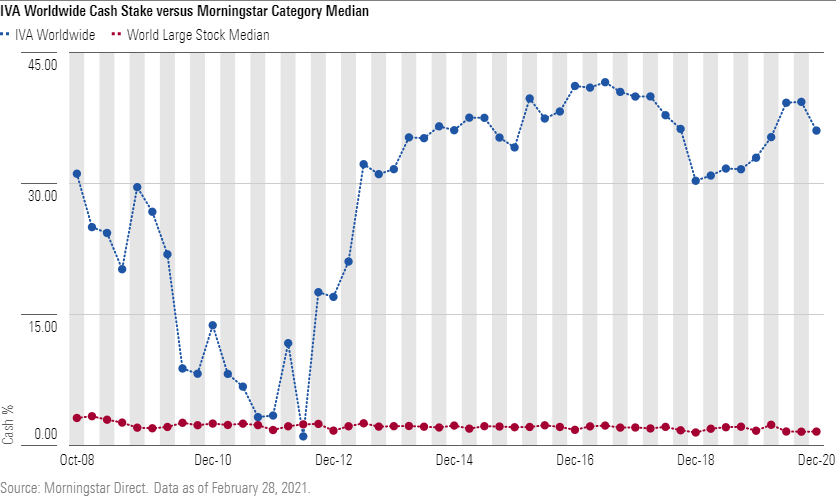

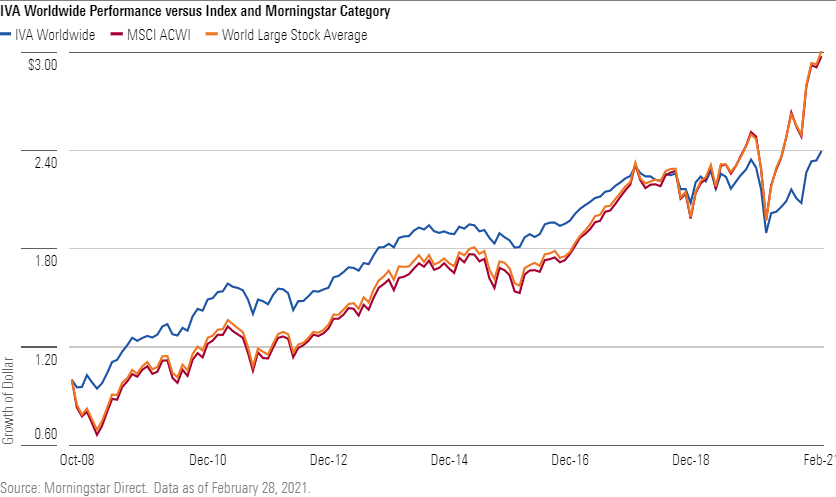

Performance started off well, too, in relative terms. With de Vaulx and de Lardemelle reluctant to invest fully in such an uncertain climate, the fund’s large cash stake--it had 31% in cash at the end of October 2008, and still had 25% at year-end--insulated it from the ongoing meltdown. IVA Worldwide’s I shares posted a positive 2.8% return in the final quarter of 2008, versus losses of 21.9% for the S&P 500 and 22.4% for the MSCI All-Country World Index--the fund’s chosen benchmark.

Things Get Complicated

Market conditions changed, and then changed again, but IVA’s caution remained. The managers never could find enough high-quality companies at low-enough prices to meet their strict value standards. They weren’t willing to compromise those standards, and they didn’t want to pour the cash stake into the existing holdings, for doing so would raise those stocks’ weightings to uncomfortable levels. As a result, both funds consistently held cash levels of more than 20% of assets. In late 2009 Worldwide’s cash stake hit 42%. Though it soon fell back to the 17%-30% range that it maintained for the next five years, by 2014 IVA Worldwide’s cash stake rose into the 30%-40% range and never looked back. In an era where the markets were generally rising, this immense pile of money sitting on the sidelines exerted quite a drag on performance.

The magnitude of IVA Worldwide’s early outperformance helped buoy its longer-term record for a while, as did its relative resilience in the briefer downturns in the following years. Thus, by late 2014, IVA Worldwide had grown to $10.1 billion in assets.

But that was the high point. There were a few stock-picking missteps, but it was mostly the extreme size of the cash pile--rare even for other value investors--that led to lagging performance and a continuous stream of outflows. The redemptions accelerated in 2019, when the fund’s return fell far short in a big rally. By the end of that year IVA Worldwide’s assets had plunged to $5.4 billion. Sibling IVA International’s fortunes followed a similar pattern, at lower asset levels.

Then came 2020.

Exhibit 2

A Year to Forget

One might assume this defensive shop would again top the charts in the market crash that accompanied the early spread of the coronavirus. However, this crash was different from prior ones. The early-2020 market turmoil not only favored growth stocks over value, but was quite brief as well. With its near-40% cash stake providing a cushion, IVA Worldwide did outperform from Jan. 21 through March 23 (the high and low points of the MSCI ACWI Index), but it still lost 25.9%, failing to provide the resilience many clients expected. They let de Vaulx know of their displeasure. Worse, although the managers did some buying, they did not make a meaningful dent in the fund’s huge cash stake despite the dramatic drop in prices.

De Lardemelle and de Vaulx told Morningstar that the companies they had most faith in didn’t become that much cheaper; that their estimates of the intrinsic value of other firms had declined along with their share prices, meaning the stocks weren’t any more appealing than before; and that the rebound came so quickly that it cut their opportunities short. The IVA funds can also own bonds, and did own a substantial amount of corporate bonds in IVA’s early life, but the managers said that bonds weren’t attractive during the pandemic crash, either.

Shareholders, unhappy with the failure to seize the opportunity presented by the steep decline in prices, continued to sell. And having failed to hold up as well as it perhaps should have during the downturn, IVA Worldwide then--unfortunately for shareholders--did follow its typical pattern in the strong rebound that followed, lagging by wide margins. At the end of 2020, IVA Worldwide had just $2.1 billion in assets--less than half the amount from just 12 months earlier.

Losing Key Players

But cash piles and unimpressive performance weren’t the only reasons the outflows continued. Just as damaging, or perhaps more so, were the departures of the only two other high-profile leaders at IVA besides de Vaulx.

The first surprise came in July 2020, when comanager and co-CIO--and IVA cofounder and partner-- de Lardemelle left the firm.

IVA didn’t provide an explanation. But a meaningful divergence between the investment outlooks of the two managers had appeared in the months since de Lardemelle was promoted to co-CIO in autumn 2019. Specifically, de Lardemelle was more willing to invest the cash hoard than de Vaulx was.

Concrete evidence appeared when de Lardemelle was named sole manager of IVA Global, the European version of IVA Worldwide, in autumn 2019. At that time, IVA Global and IVA Worldwide had nearly identical portfolios, the typical situation when a firm offers a “clone” vehicle in a different region. That quickly changed; at IVA Global, de Lardemelle invested some of the fund’s cash, buying stocks that IVA Worldwide didn’t own--indicating that de Vaulx didn’t think as highly of them. In addition, in a client conference call de Vaulx and de Lardemelle had differed on the health of the economic climate, with de Lardemelle more optimistic.

It’s not clear whether de Lardemelle decided to leave on his own or was encouraged to leave. But in the end it doesn’t matter. The result was that IVA was left with de Vaulx as the only person with any portfolio-management experience, and no one with whom to share duties such as client contact and overseeing the analysts and traders. De Lardemelle was also the most obvious successor to de Vaulx, who, in his late 50s, is about 10 years older. After de Lardemelle’s departure, de Vaulx told Morningstar that despite their experience and long tenures, none of the current analysts could fill either the comanager or successor role at the time, and he had no plans to hire anyone from the outside for that purpose. He began working more closely with an experienced analyst, Adam Ackerman, who was willing to take on additional responsibilities, but a promotion to comanager (and thus to potential successor) didn’t seem likely to happen anytime soon.

De Lardemelle’s departure didn’t go over well with some IVA clients. Although de Vaulx was the senior partner and driving force at the firm, it was reassuring to have another experienced manager--and a likely successor--in place. And de Lardemelle was, in some ways, more at ease in handling the client-relations duties that come with the job.

De Vaulx took back the reins of IVA Global and almost immediately sold most of the new stocks that de Lardemelle had bought.

IVA then lost another key player. In December 2020, managing partner Michael Malafronte, who had been dealing with health issues, left the firm. Malafronte, like de Lardemelle, had been a founding partner of IVA. He served in a role similar to a CEO, handling the business aspects of the firm. He, too, was not replaced. The dual departures added to the responsibilities on de Vaulx’s shoulders.

The Finale

In the meantime, shareholders continued to withdraw their money. With another $283 million of net redemptions in the first two months of 2021, IVA Worldwide’s asset level was $1.9 billion at the end of February. IVA International, which in 2017 had boasted more than $4 billion in assets, had $500 million or so. (IVA Global, the Europe-based vehicle, was down to about $200 million.) The firm also had assets in institutional accounts, though it’s not clear how much.

IVA could have cut costs and continued on. But for how long? A former IVA employee says a modest round of layoffs had already occurred in 2020. The flow trends clearly were headed in the wrong direction. Add in the departures of the managing partner and the comanager/successor (an analyst had departed in late summer, too), and it’s clear some hard decisions had to be made. Why de Vaulx decided to fold rather than try to sell--or reduce costs and hope for a turnaround--and why he did so abruptly and with so little communication, are questions that are difficult to answer. But one can try.

A hint that such an unusual outcome could occur did come a few years earlier. When Morningstar analysts undertook one of our periodic reviews of IVA as a firm, we asked Malafronte what would happen if, for any reason, de Vaulx and de Lardemelle were no longer around. He said IVA could keep operating successfully with just one of the managers in place, but without either one, the firm would send money back to clients and close up shop. He said he recognized that shareholders had invested in IVA’s funds because of the managers and their specific brand of value investing, and if those managers were gone, the only fair move would be to return their investment.

Although the circumstances didn’t quite fit that pattern--de Vaulx was still there--the fact that a fund shop’s quasi-CEO would candidly express such a plan illustrates that IVA saw itself quite differently than most asset managers.

Even so, IVA did not have to liquidate when it did. So why did it? When contacted by Morningstar, de Vaulx declined to comment. Another former IVA employee, who had been with the firm for many years and holds de Vaulx in high regard--even after being abruptly terminated along with nearly everyone else--says that de Vaulx always remembered that renowned value investor Warren Buffett had returned assets to shareholders early in his career when circumstances seemed to warrant such a course, noting that this precedent may have played a role in de Vaulx’s thinking.

IVA sources confirmed that the firm did pay bonuses on schedule in early 2021 and offered modest severances. They also said there was nothing untoward going on at the firm and no big operational issues, such as a problematic debt burden or other analyst departures.

Thus, the impetus for liquidation seems to have been de Vaulx’s feeling that it had become too difficult go on, given the relentless stream of outflows, rapidly diminishing asset base, and unfavorable market climate. The added burdens left by the absence of de Lardemelle and Malafronte must have further increased the pressure.

After Malafronte left in December, only two of IVA’s six founding partners remained at the firm: de Vaulx and longtime analyst Thibaut Pizenberg, who began working with de Vaulx and de Lardemelle at First Eagle 20 years ago.

Interestingly, the market turned in favor of value starting in late 2020, and IVA Worldwide was doing decently well in 2021, landing in the 38th percentile of the world large stock Morningstar Category through the end of February. As we have seen, though, that was not enough to stop the outflows.

Several industry sources have told Morningstar that another value shop, and perhaps other firms, approached IVA to discuss a potential sale or other strategic options, but that de Vaulx declined to consider the offer or offers. Why he would do that might seem puzzling; most firms would sell or merge all or part of their business instead of simply liquidating the funds and closing down. But knowing his determined, forceful personality, and that he had already left one firm owing to disagreements with ownership, it’s possible that at this stage of his career de Vaulx had no interest in working for a boss again, even one that may have broadly shared his investment philosophy. And it’s doubtful that a firm exploring a deal with IVA would have wanted an IVA without de Vaulx.

Furthermore, IVA’s clients likely would not have embraced a merger with a more typical value shop. Financial advisors and investors had sought out IVA because of its dedication to the uncommon capital-preservation strategy that de Vaulx had learned from Jean-Marie Eveillard years before.

Exhibit 3

A Portent?

It might be tempting to consider IVA’s demise a foretaste of what may be in store for other value-oriented asset managers, or any fund firm suffering substantial outflows. But that would be taking the example too far. Such companies do face serious challenges. But IVA was unique, in the amount of cash it held on a more-or-less permanent basis; the devotion to just one strict-value approach offered in only two strategies; the absence of more than one possible successor; and perhaps in the mindset of its leader.

Another Way?

Regarding another important question--could De Vaulx have handled the situation differently--the answer is yes. We don’t know what happened behind the scenes, but there appears to be no logical reason why he couldn’t have sent a letter to the advisors and shareholders who had stuck with him through thick and thin for so many years, providing a modicum of explanation why he took this course. Or, failing that, at least thanking the advisors and shareholders for their support and regretting the way things turned out.

There remains no message on IVA’s website besides a bare-bones, two-sentence announcement of the liquidation and a link to the formal document filed with the SEC. It wouldn’t be surprising if advisors who’d believed in IVA’s cautious approach and invested a lot of their clients’ assets with the firm are frustrated and dismayed. IVA’s silence is particularly curious because de Vaulx has always been one of the most-candid portfolio managers, a trait his investors likely appreciated.

Conclusion

Given the context described above, one might be able to understand, if not agree with, de Vaulx’s decision to throw in the towel rather than attempt to soldier on under such challenging conditions. Though his decision to consistently hold so much cash made IVA an outlier and turned out to be detrimental, de Vaulx wasn’t the only knowledgeable investor who has considered markets to be overpriced for a long time. Had the pandemic-induced bear market of early 2020 continued for an extended period or even deepened--as many market observers expected, for good reason--IVA’s fortunes might have turned out differently. It’s worth remembering that Eveillard himself faced criticism and outflows when his approach fell deeply out of favor in the overheated growth climate of the late 1990s, only to be vindicated when that market collapsed in March 2000.

De Vaulx never claimed that IVA’s funds would be fully invested, or anything close to it, and he took responsibility for his decisions. He never tried to shift the blame to others (except, perhaps, the markets).

In the end, perhaps the decision to liquidate shouldn’t be that surprising. The underperformance, the steady stream of outflows, and until very recently, the market’s seemingly relentless growth tilt, on top of the internal departures, all placed major hurdles in IVA’s path. And with de Vaulx left alone at the top, in effect the firm resembled a hedge fund dedicated to one person’s vision, and hedge funds, unlike mutual funds, do often liquidate rather than sell, merge, or try to stick it out.

That said, some words of explanation or gratitude would have been appreciated. There may be real or potential legal reasons for the lack of detailed communications, but it’s hard to believe it was impossible to say anything at all.

Note: The author was a shareholder of IVA Worldwide from shortly after its inception until late March 2021, and continues to own First Eagle Global and First Eagle Overseas.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)