Don't Worry Over Currencies

The impact of currency movements on equity allocations has been negligible over the long term, so investors holding unhedged Medalist funds should stay the course.

Note: This article is an excerpt from the Morningstar research paper The Impact of Foreign-Currency Movements on Equity Portfolios. A copy of the paper can be found here.

The U.S. dollar has staged an impressive rally over the past year. Although it has taken a bit of a breather recently, there are reasons to expect the dollar to remain strong, at least over the next year or two. The U.S. Federal Reserve is likely to raise rates in the next 12 months, which would be the first increase since 2006. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank, on the other hand, plan to maintain extremely low interest rates in their countries for the foreseeable future. Both central banks hope to stoke inflation and keep the yen and euro weak relative to the dollar in an effort to boost exports. These measures should support a stronger dollar, at least relative to the yen and euro.

With the U.S. dollar's recent rise, many investors are taking a closer look at their portfolios' currency exposures. Most international-equity funds do not hedge their foreign-currency exposure, which means that their performance reflects both equity market performance and currency movements relative to the U.S. dollar. When the U.S. dollar rises against foreign currencies (or when foreign currencies weaken against the U.S. dollar), the performance of unhedged international-equity funds is negatively impacted by exchange-rate translation effects. The use of currency hedges in an international-equity fund, on the other hand, can mitigate negative, as well as positive, exchange-rate translation effects.

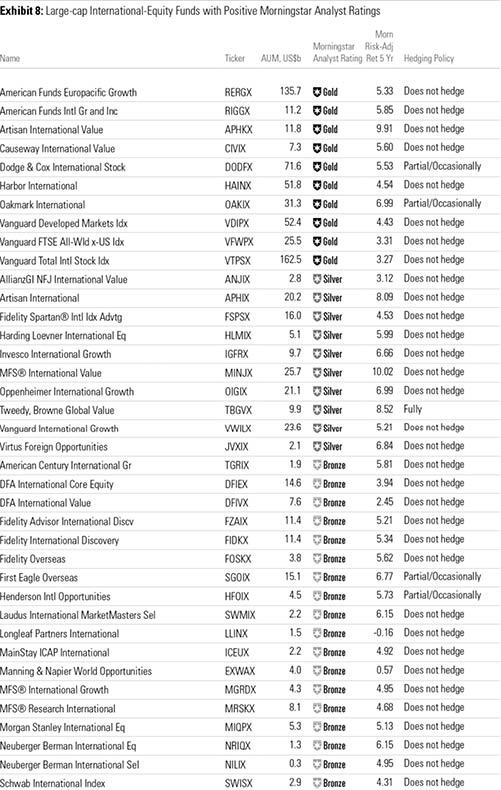

In this paper, we will look at the history of the U.S. dollar's performance over the past 40 years, discuss the impact of foreign-currency movements on international-equity portfolios, and evaluate the historical risk-adjusted returns of using either a currency-hedged or unhedged international-equity strategy within a diversified portfolio. At the end of the report, we include a brief discussion of the currency-hedging policies of international large-cap equity funds with Morningstar Analyst Ratings. We also include a list of all U.S.-listed currency-hedged exchange-traded funds.

We found there is no significant difference in long-term risk-adjusted returns between portfolios that use a currency-hedged international-equity strategy and portfolios that use an unhedged international-equity strategy. As such, long-term investors should focus on choosing well-run, low-cost international-equity funds for their portfolios and should be indifferent to whether or not the funds hedge their currency exposure.

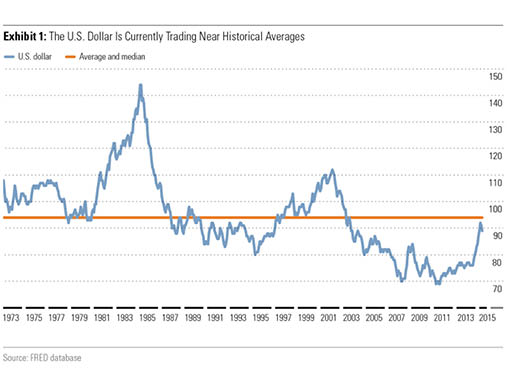

The U.S. Dollar: What Goes Up Must Come Down The exhibit below is the Federal Reserve's Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index: Major Currencies. It shows the performance of the U.S. dollar against a basket of currencies, which includes the euro (58%), the yen (14%), the British pound (12%), the Canadian dollar (9%), the Swedish krona (4%), and the Swiss franc (4%). Data for the index starts in 1973, just after industrialized countries moved away from fixed exchange rates and toward fiat, free-floating currencies.

The index's base value of 100 was set on March 1, 1973. Over the subsequent years through May 1, 2015, the index's average and median values have both been 94, which is slightly higher than the index's value of 89 as of May 1, 2015.

Over the past 40 years, the U.S. dollar has made large, multiyear cyclical movements. Since 1973, there have been two peaks--one in 1985 and the other in 2001. In the early 1980s, the dollar rose following then-Fed chair Paul Volcker's attack on inflation via double-digit interest rates. The dollar then fell after the Plaza Accords, where central banks from the United States' main trading partners worked together to engineer a U.S. dollar decline.

The events leading up to the 2001 peak included the technology bubble, the U.S. stock market rally, the introduction of the euro in 1999, and the Asian financial crisis, all of which helped drive strong global demand for the U.S. dollar. The dollar's subsequent decline was driven by weak domestic fundamentals (large and rising trade and fiscal deficits), which existed through the late 1990s but whose effect was overwhelmed by trends occurring outside the U.S.

The 2008 financial crisis is another example where, despite a weak economic environment in the U.S., strong external demand for the U.S. dollar helped drive a small rally in the U.S. dollar. The dollar has been and continues to be considered a safe-haven currency, so during market crises, investors flock to the U.S. dollar.

Currency valuation is a complicated topic, as this condensed history of the U.S. dollar as a free-floating currency illustrates. Over the long term, a nation's interest rate, inflation, growth, and current account balances generally drive currency values. This is consistent with the concept of purchasing power parity, which occurs when the exchange rate between two floating currencies settles where the purchasing power of the two countries' currencies is at par. So, in theory, over the long term, free-floating currencies should not generate any real returns.

But over the short and medium term, the value of a currency can significantly deviate from its fundamental value for myriad reasons, including government intervention and trends occurring outside the U.S. In aggregate, however, the U.S. dollar has moved cyclically since it became a free-floating currency in 1973. In fact, the index has the same 42-year average and median value of 94, suggesting that the cycles, whether long or short, have been fairly symmetrical. Simply put, what goes up must come down.

The dollar's most recent rise, which started in 2014, was fueled by expectations that the Fed would begin raising rates in the first half of 2015 and the commencement of the eurozone's quantitative easing program. But it is worth noting that in early 2014, the U.S. dollar was trading at about a 30% discount from its highs in 2002, so it may have been undervalued and poised to rally. As of May 2015, the U.S. dollar index is trading just below its long-term average, which may suggest the U.S. dollar's rally is losing steam. In fact, in the spring of 2015, the Fed began to take a more dovish tone regarding the timeline for rate increases, and the dollar weakened slightly. Notably, this statement from the Fed came as U.S. companies were reporting first-quarter earnings, when a number of multinational firms said the rising dollar had hurt revenues from overseas markets.

In an International-Equity Portfolio, Currency Fluctuations Are Neutralized Over the Long Term Because currencies theoretically provide no real returns, long-term investors should be indifferent to using a currency-hedged (before fees) or unhedged international-equity strategy. But has this actually been the case over the past few decades?

The simplest way to assess the impact of currency movements is to compare the currency-hedged and unhedged performance of a broad international-equity index. To do this, we used the MSCI Europe, Australasia, and Far East Index (also known as the MSCI EAFE Index) and its hedged counterpart, the MSCI EAFE 100% Hedged to USD Index. The MSCI EAFE Index, a common benchmark for international-equity portfolios, is an unhedged market-cap-weighted index covering 21 developed markets outside of North America. The returns of the 100% hedged index include the estimated cost of hedging by using one-month currency forwards. Over the past 25 years, the annual cost to hedge has been in the range of plus/minus 300 basis points. We did not use an index that includes emerging markets because hedging certain emerging-markets currencies is very costly or difficult to execute efficiently.

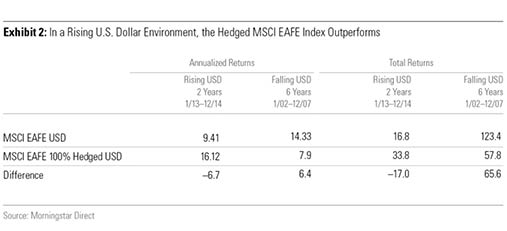

Since 1973, the U.S. dollar has regularly trended in one direction for a number of years. With 20/20 hindsight, being in a hedged (or unhedged) strategy at the right time can result in significant outperformance relative to an unhedged (or hedged) strategy. Starting in 2002 when the dollar began to decline, the unhedged index would have outperformed the hedged index by about 600 basis points per year on average over the subsequent six years. Conversely, in a rising dollar environment, the hedged index would outperform an unhedged index.

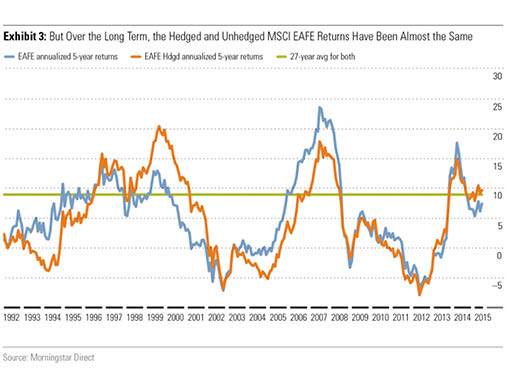

In Exhibit 3, a graph of the hedged and unhedged MSCI EAFE indexes' rolling five-year returns illustrates how the hedged index (the orange line) tends to outperform when the dollar is rising (for example, 2014-15) and the unhedged index (the blue line) tends to outperform when the dollar is falling (for example, 2001-07). But over the long term, exchange rates have little impact on returns. In the 27 years from 1988 through 2014 (data for the MSCI EAFE 100% Hedged to USD Index starts in 1988), the hedged index outperformed the unhedged index by only 30 basis points annualized. (There can be small differences in annualized returns depending on the start and end date. If the end year were 2013 instead of 2014, the unhedged index would have slightly outperformed the hedged index by 10 basis points, annualized. The inclusion of 2014 returns made a difference because the U.S. dollar rose sharply against major currencies that year.)

These small differences in returns between the currency-hedged and unhedged MSCI EAFE indexes suggest that long-term investors should be indifferent to hedging their international-equity strategies.

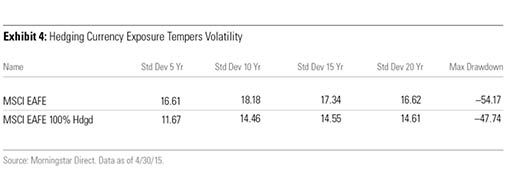

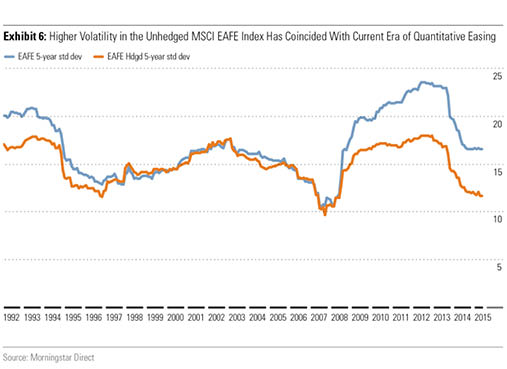

Foreign-Currency Fluctuations: Are Investors Compensated for This Risk? The long-term returns of hedged and unhedged non-U.S. strategies may be similar, but their volatility profiles are different. The unhedged MSCI EAFE Index has exhibited higher volatility relative to the MSCI EAFE 100% Hedged to USD Index because of the former's exposure to foreign-currency fluctuations.

This may be partly attributable to the fact that the U.S. dollar is considered a safe-haven currency and tends to rise when risk aversion is high. In other words, when volatility spikes in global markets, an unhedged international-equity fund gets hit by falling international-equity markets, as well as a rising U.S. dollar and falling foreign currency. During the 2008 global financial crisis, the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index had a maximum drawdown of 54.2%, whereas the hedged version declined by 47.7%.

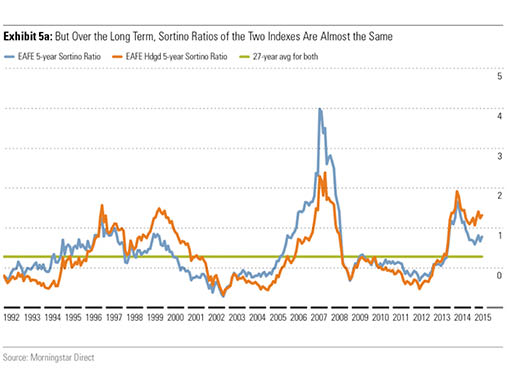

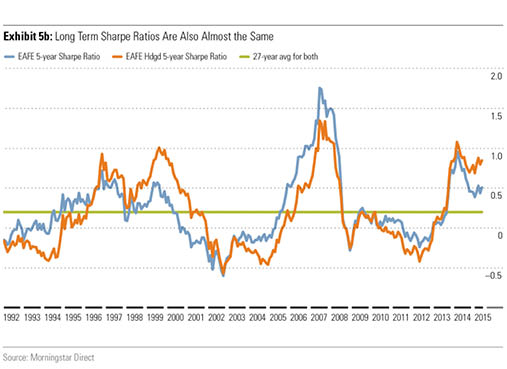

But despite the higher volatility of the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index, the long-term risk-adjusted returns of the unhedged and hedged MSCI EAFE indexes tend to be very similar. In a chart of rolling five-year Sortino ratios (a measure of risk-adjusted return that only incorporates downside volatility), the hedged and unhedged MSCI EAFE indexes take turns leading, with the hedged index generally outperforming when the U.S. dollar is rising and the unhedged index generally outperforming when the dollar is falling. The same pattern exists for the indexes' Sharpe ratios (a measure of risk-adjusted return that incorporates both upside and downside volatility). Over the long term, the annualized risk-adjusted returns of the hedged and unhedged MSCI EAFE indexes (as represented by the green lines in Exhibit 5) are almost the same.

This suggests that investors are compensated over the long term for withstanding the additional volatility from currency movements in the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index.

However, since the 2008 financial crisis, a number of major events have had a significant impact on currency movements and equity markets. There have been market events, like the European sovereign-debt crisis, which started in 2010. But there have also been deliberate efforts by national governments and central banks to stimulate their respective economies, and these moves have had an impact on the value of their currencies. These include quantitative easing in the U.S., which started in 2009, Abenomics in Japan, which started in 2013, and quantitative easing in the eurozone, which started in 2015. Notably, this current era of increased governmental interference has coincided with sustained higher volatility of the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index, relative to its hedged counterpart.

While the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index may have been more volatile since 2008 (see Exhibits 5 and 6) its risk-adjusted returns were fairly similar to those of the hedged MSCI EAFE Index through 2013. In addition, in the 1990s, there was a period when the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index was more volatile, and, during that time period, the unhedged index consistently outperformed its hedged peer on a risk-adjusted basis. Currently, we are in a period where the currency-hedged MSCI EAFE index is outperforming, thanks to the strengthening dollar. But over the past 40 years, history has shown that the interplay of government intervention and currency fundamentals results in a cyclical movement of the U.S. dollar. These drivers may have an impact on the duration of the U.S. dollar's rise against other currencies, but they haven't had an impact on the cyclical nature of the U.S. dollar's movements.

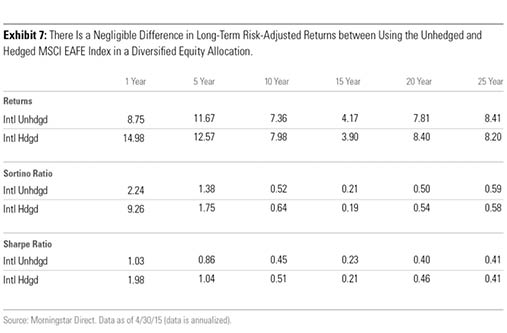

What Plays Well in a Portfolio? When determining whether to use a currency-hedged international-equity fund, it is important to consider the portfolio's other constituents. Investors typically hold international-equity funds alongside their U.S. equity funds to create a diversified portfolio. We looked to see whether investors would generate better long-term risk-adjusted returns if they combined the hedged or unhedged MSCI EAFE indexes with the S&P 500. In the exhibits below, we show a portfolio composed of the S&P 500 (at 60%) and the MSCI EAFE Index (at 40%), rebalanced annually. The first portfolio uses the unhedged MSCI EAFE Index, and the second portfolio uses the hedged MSCI EAFE Index.

Despite the recent strong one-year outperformance of using the hedged MSCI EAFE index, the returns of using either strategy start to look fairly similar in time periods of five years or more. It takes a long time for the risk-adjusted returns to look similar, but the Sortino and Sharpe ratios do converge over the longer term.

Conclusion Historically, there is no evidence to conclusively say that long-term investors should or should not hedge currency exposure in their international-equity allocation. However, the question to hedge or not hedge has become a popular topic, especially as currency-hedged ETFs have recently generated category-topping performance and attracted very strong asset flows.

Over the past few years, central banks in the U.S., Japan, and Europe have been fairly transparent about their quantitative-easing programs, so it hasn't been that difficult to predict the performance of the yen and euro against the U.S. dollar. But central banks are not always so forthcoming: In January 2015, the Swiss National Bank surprised global markets when it decided to drop its exchange-rate cap, which sent the Swiss franc soaring.

The argument for hedging currency exposure in an international-equity portfolio assumes that we will continue to see a falling euro and falling yen against the U.S. dollar and equity markets will continue to rally in those two regions. It also assumes that hedging is beneficial in times of market crisis, as the U.S. dollar continues to be considered a safe-haven currency. These trends may hold true in the medium term but perhaps not the long term. In addition, the current trends that have produced strong returns in currency-hedged strategies (that is, a decline in the yen and euro, coinciding with a rally in equity markets in Japan and the eurozone) are quite rare, so it is likely the recent easy-money opportunity may have already passed.

Political maneuvers may have an impact on short-term currency and stock market valuations, but over the long term, valuations tend to be driven by fundamentals. Over the past four decades, all the drivers that can have an impact on the U.S. dollar, such as economic health, external trends, and government interference, have resulted in fairly symmetrical, cyclical movements in the U.S. Dollar Index. Should this continue to be the case, currency movements should be neutralized in the long term. As such, investors should continue to be indifferent to holding a currency-hedged or -unhedged international-equity strategy.

Betting on currency movements is generally a fool's game and should be avoided by the average investor. The same could be said for predicting political decisions and their impact on currencies and equity markets. Investors holding well-run, low-priced, and unhedged diversified international-equity funds should stay put and stay the course.

International-Equity Funds With Morningstar Analyst Ratings The international large-cap equity funds below all carry a Positive Morningstar Analyst Rating and can serve as core holdings for investors' non-U.S. stock allocation. Most of these funds do not hedge their foreign-currency exposure, and only about a dozen hedge even a portion of their currency exposure. Even rarer are actively managed funds that hedge all of their currency exposure. It should be noted that determining whether a fund hedges, and to what degree, is often not an easy task. Disclosure in this area tends to be poor.

The only fund that consistently hedges all of its currency exposure and received a Morningstar Analyst Rating is

Such conservatism is a common theme among the remaining actively managed funds that partially hedge their foreign-currency exposure. These equity managers hedge to reduce risk and not to speculate on the future performance of a currency. They tend to look at risk in absolute terms (such as the risk of permanent loss or capital destruction) rather than in relative terms (such as the risk of lagging a benchmark or peer group).

For a list of the open-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the closed-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the exchange-traded funds we cover, click here. For information on the Morningstar Analyst Ratings, click here.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/de44b91c-c918-4e53-81c3-ce84542f3d36.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/de44b91c-c918-4e53-81c3-ce84542f3d36.jpg)