Why Yields on Floating-Rate Bank Loans Aren't Floating (Yet)

Interest-rate floors have become the norm for bank loans amid persistent near-zero interest rates.

Bank loans, also called leveraged or floating-rate loans, are a unique offering within the fixed-income complex. In recent years, bank loans have attracted attention as many investors look to protect their bond portfolios from an eventual rise in interest rates. Indeed, this Morningstar Category saw an estimated $67.5 billion in estimated net inflows in 2013. Despite significant outflows in 2014 and through the first quarter of 2015, the category has still doubled in size during the past three years.

With such emerging asset classes there can often be some misconceptions because of a relative lack of familiarity. Since bank loans have only recently become part of investors' fixed-income tool kit, it's worth taking a closer look at one of the asset class' distinguishing characteristics.

There are a number of differences between bank loans and traditional, core fixed-rate bonds, as we've discussed before. Bank loans are typically made to below-investment-grade or junk-rated companies, although they are also typically secured by a company's assets, so they tend carry less credit risk than high-yield bonds to the same company. They also offer floating rates, an attractive quality for investors concerned about rising bond yields. In this article, we'll focus on this interest-rate risk. We offer a brief primer the mechanics of floating rates, including an overview of interest-rate floors--an important feature that can determine whether or not the interest rate on a particular bank loan will reset.

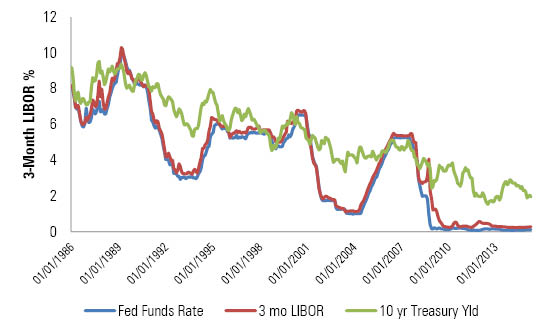

The first thing to understand about the floating-rate nature of bank loans is that their yields "float" along with Libor (the London Interbank Offered Rate), not the more widely watched 10-year Treasury yield or federal-funds rate. Libor represents the rate at which the major banks can borrow from each other in the London interbank market over various time periods, ranging from overnight to one year. Today, there are nearly 20 contributing banks around the world that are surveyed in order to set Libor. As a rate determined by the market on a daily basis, Libor can lead changes in the federal-funds rate (which is set by the Federal Open Market Committee at its meetings once every six to eight weeks, at most) and can therefore be viewed as a more accurate reflection of global interest rates.

The rate-reset mechanics are fairly straightforward. For leveraged bank loans, the most common reference rate is three-month Libor. Most bank loans reset their interest payments on a quarterly basis. So, for instance, if Libor was 1.5% and a particular loan was issued with a spread of 4.0%, that loan's annualized interest payment would be 5.5% over the quarter.

However, there's a twist. An often overlooked feature included in the term structure of most bank loans is what's called an interest-rate floor. Consider the bond used in the previous example. If Libor fell to 0.5% and there was no interest rate floor, then the expected interest payment on the loan would be 4.5%. However, if that loan was issued with an interest rate floor of 1.0%, then its interest payment would reset to 5.0%. In this case, Libor dipped below the interest-rate floor, so rather than Libor plus the spread, the interest payment becomes the interest-rate floor plus the spread.

Interest-rate floors are designed to offer the lender some protection from falling or very low interest rates. With near-zero interest rates during the past several years, interest-rate floors became increasingly common and have helped to entice and compensate investors for assuming heightened credit risk.

However, while Libor floors have been an investor's friend in the recent low-rate environment, they also mean that bank-loan yields will not be as quick to adjust when Libor finally begins to rise. In our example, for instance, if Libor jumped to 0.75% from 0.50% the interest payment would not reset, but remain at 5%. Despite a rise in Libor, it still remained below the interest-rate floor.

This is an important feature for bank-loan investors to keep in mind. Those anticipating a bump in yield from their bank-loan investments may have to show some patience before rates on those investments actually reset.

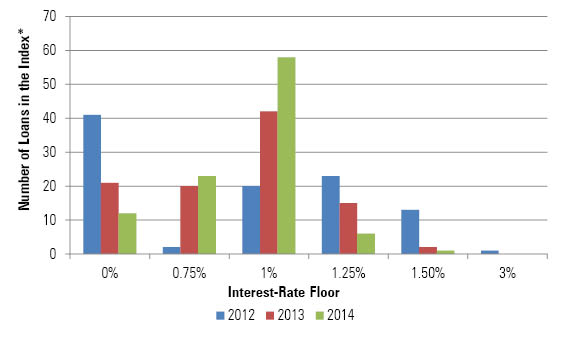

To gauge how interest-rate floors can affect a portfolio of bank loans, we can take a look under the hood of the oldest and most popular bank-loan exchange-traded fund, PowerShares Senior Loan BKLN. This ETF tracks the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index. Exhibit 1 breaks down the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index by interest-rate floor during the past three years. As shown in the chart, as of 2014, the vast majority of loans featured Libor floors. Approximately 65% of BKLN's benchmark is composed of loans with a Libor-floor of 1.0% or higher. Of the 100 loans that constitute the index, 87 have an interest-rate floor, with 64 of those at 1.0% or more.

Exhibit 1

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. *Data based on the composition of the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index.

As of year-end 2014, the weighted average Libor floor for BKLN's benchmark was about 0.85%, up from 0.71% in October 2012. Contrast that against three-month Libor, which clocked in at 0.28% as of May 8, 2015. Given that Libor remains well below the portfolio's average interest-rate floor, BKLN investors won't see upward adjustments in their interest payments until Libor climbs above that floor. In fact, there isn't likely to be a meaningful adjustment to BKLN's yield until Libor is higher than 1%, a level last seen in April 2009.

Exhibit 2

Sources: ICE Benchmark Administration Limited, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

As a result, investors who prize bank loans for their rate protection should keep a few key points in mind. First, the rates on bank loans only adjust with increases in Libor, so increases in longer-term bond yields don't have a direct effect on their yields. (During 2013, for example, Libor stayed near zero even as 10-year Treasury yields spiked). Secondly, given that the market is anticipating a slow and gradual increase in rates, it will be important to keep the impact of interest-rate floors in mind even as Libor begins to rise.

Indeed, while the floating nature of interest payments on bank loans significantly reduces interest-rate risk, it doesn't eliminate it completely. If interest payments on a fund like BKLN don't immediately reset higher, it doesn't mean that it is broken or not performing as advertised. It simply means that the reference rate has yet to cross the threshold set by the interest-rate floors.

Despite these caveats, bank loans are likely to prove their worth if there is a sustained increase in Libor and it increases above the typical floor of 100 basis points. These funds may therefore still have a role to play for investors who are concerned about rising rates and are willing to tolerate the imbedded credit risk in these loans.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc.'s Investment Management division licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)