Taking a Strategic Approach to Currency Exposure

A strong dollar aside, think risk first when it comes to currency exposure.

Note: We are re-featuring this article as part of Morningstar's May 2015 International Investing Week special report. This article was originally posted on Morningstar.com April 26, 2015, and appeared in the April/May 2015 issue of Morningstar magazine.

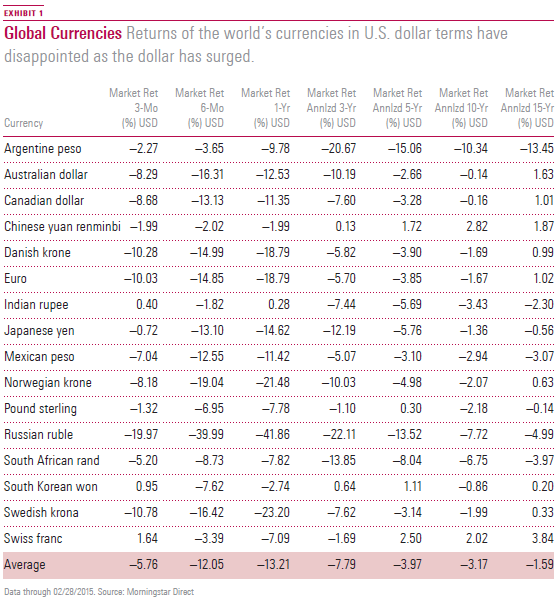

The U.S. dollar looks invincible these days (Exhibit 1). For U.S. investors, its surge can make the case for hedging foreign-currency exposure seem like a one-way argument. Why own other currencies? The dollar gained 17.4% against the euro, 13.6% against the yen, and 7.4% against the pound over the past year through Feb. 23.

Moreover, there are good reasons why the dollar may remain strong, at least over the short term. The U.S. Federal Reserve seems determined to raise rates at some point in 2015, which would be the first time it's done that since 2006. A rate increase would likely support the dollar, at least relative to the yen and euro. That's because both the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank plan to keep monetary policy loose for the foreseeable future. Both central banks hope to stoke inflation as well as keep their currencies (the yen and euro) weak relative to the dollar in an effort to boost exports. In fact, a group of finance ministers and central bankers (representing the G-20 countries) recently admitted that currency depreciation was a goal of monetary policies like quantitative easing.

Nonetheless, while the current trends in currency markets seem strong, they won't last forever. As with equities and bonds, currencies also tend to come back to earth after periods of strength. This happens either through market corrections or by direct government intervention. Thirty years ago, the G-7 countries, faced with a similarly strong dollar, agreed to weaken the dollar through the Plaza Accord. These days, the United States seems willing to tolerate a strong dollar, but its stance could change if it starts hurting economic growth.

With this as a backdrop, it's easy to understand why many investors--especially those in the United States--are interested in strategies that fully hedge their foreign-currency exposure. Besides, it's hard to feel good about owning currencies that are being actively depreciated. But especially during times like this, it's worth taking a step back to revisit basic investing principles.

How to Think About Currency Exposure As a starting point, no matter in which country they reside, investors shouldn't manage their currency exposure based on current conditions. Currency management demands the same sort of long-term thinking that applies to other strategic asset-allocation decisions.

That said, how to approach managing currency exposure isn't clear cut. (Indeed, given the global operations of many large-cap companies, it can be difficult to assess what one's true currency exposure even is.) Unfortunately, there's little consensus around whether currency exposure within an equity portfolio should be hedged or not. For U.S. investors, there have been long stretches of a decade or two in which hedging would have been advantageous--and vice versa--but it's nearly impossible to determine in advance which option will deliver higher returns.

Of course, there are no guarantees with equities or bonds either. Both equities (think Japan since 1989) and bonds (U.S. Treasuries from 1951 to 1981) have had similarly long dry spells. But at least an investor continues to receive dividends and interest payments. Although current valuations play a huge role in future returns, equities and bonds are designed to deliver a return over time. Even long-term U.S. Treasuries still delivered small gains (1.8% annualized) during their 30-year bear market. The same cannot be said for currencies, although some studies have found that the premium for foreign equities owes in part to currency risk. Currency returns are a zero-sum game. The gains are always in relation to the losses of another.

But currency exposure still needs to be managed, as it can have a significant impact on a portfolio's risk profile. Although the future is unknowable, investors can at least make conscious decisions about which risks they take on.

In at least one sleeve of an investor's portfolio, the guidance is clear. Investors in foreign bonds are best served hedging any resulting currency exposure. The reason for hedging currency exposure in a bond portfolio is that currencies tend to be much more volatile than the underlying bonds, especially of the investment-grade variety. Currency swings can easily overwhelm a bond's income stream and price movements. As a general rule of thumb, the less volatile and the more certain the cash flows from an underlying investment, the more it pays to hedge.

Foreign-Equity Portfolios The picture is less clear when it comes to foreign-equity portfolios. Most studies have found that currency effects offset one another over the long term. Therefore, if one decides to hedge, it means accepting returns that in theory will be lower than the alternative by the cost of the hedges. But that's not the end of the story, at least for U.S. investors.

Hedged foreign-equity portfolios tend to be less volatile than unhedged portfolios, especially during equity market sell-offs. (For non-U.S.- based investors buying U.S. stocks, this is less the case.) The U.S. dollar is a reserve currency after all and is still considered a safe haven. This shows when looking at the hedged and unhedged returns of the MSCI EAFE Index over time. Over the trailing 15 years, the unhedged version of this index has a standard deviation of 17.3% versus 14.5% for the hedged version.

This same dynamic exists with

However, unhedged portfolios can deliver potential diversification benefits of their own. But these benefits depend on two things: the volatility of the currencies relative to the underlying equities and, more importantly, the correlations between these two baskets. If the correlations are strongly negative, then being unhedged leads to lower overall risk as losses in one asset may be offset by gains in another (the basic idea behind all diversification). If correlations turn positive, then it's better to be hedged, at least from a risk-management standpoint.

The problem with this is that correlations can change over time, and it's difficult to know in advance whether future correlations will be positive or negative. So, there's no guarantee that the diversification benefits of an unhedged portfolio will be realized.

What To Do? So, what's the best approach given all of this uncertainty? One option is to adopt the 50% rule--hedging half of one's foreign-equity exposure and leaving the other half unhedged.

One way to implement this would be to separate developed-market exposure from the rest of the foreign-equity portfolio. Given that hedging is cheapest in developed-market currencies, one alternative might be for investors to hedge their exposure in those countries. Investors could then carve out an allocation to emerging-markets equities, leaving it unhedged.

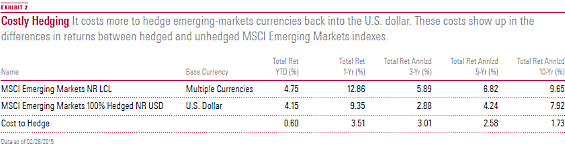

Besides diversification, there's a cost-related reason for not hedging emerging-markets currencies. Because interest rates tend to be higher in emerging markets, it's more expensive to hedge those currencies back into the U.S. dollar (Exhibit 2).

(Click to enlarge)

In addition, the currencies themselves may not be freely traded, further complicating the picture. Plus, the greater volatility of emerging-markets equities further argues against hedging the currency exposure. The same argument against hedging could apply to foreign small-cap equities, even those in developed markets. So, adopting these suggestions would leave an investor with a hedged, developed-markets, mostly large-cap portfolio (something akin to the EAFE index), and unhedged emerging markets and small-cap foreign-equity sleeves.

Trimming Currency Exposure Over Time If investors decide to not hedge currencies, Morningstar research has found that it still may be wise to trim that exposure--either through hedging or reduced position sizes--as investors get closer to retirement. For U.S. investors, that's because they will soon need to start paying dollar-based liabilities from their portfolios. So, as the day when investors need to start meeting dollar-based obligations approaches, it makes sense to reduce foreign-currency exposure.

At some point, the U.S. dollar will fall against other currencies. Investors should try to resist the temptation to predict when this will happen and act opportunistically. The recent surge of the Swiss franc, after the central bank removed its link with the euro, showed the folly of such bets. If investors are worried about the potential inflation caused by a falling dollar, for example, they should address that risk head-on. They should protect their portfolios from inflation through equity exposure, TIPS, or other real-return strategies. Besides, the dollar's recent strength against a wobbly euro and yen, as well as its strength during the 2007-09 credit crisis, is a reminder that it remains a safe haven. This could change over time, but any shift would likely be gradual. Investors are better off staying focused on the long term.

This article originally appeared in the April/May 2015 issue of Morningstar magazine.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e6b4cff4-0d77-4881-abc5-5b0b34d64bf6.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/e6b4cff4-0d77-4881-abc5-5b0b34d64bf6.jpg)