The 401(k) Millionaire: When Is It Realistic?

Be rich, or be married (and be prudent).

The Road to a Million Last column discussed if accumulating a million dollars through the 401(k) system is a reasonable goal, under certain circumstances, as Fidelity (naturally) would have it, or fantasy, as argued by Fortune's Stephen Gandel. I found for reasonable.

This column outlines the circumstances.

To define the target: One million dollars means $1 million in 2015 money--that is, in real terms. Normally, 401(k) millionaires are identified otherwise, by using nominal figures. Fidelity's study, for example, sorted by account balance, labeling every current plan that reached seven digits as a "401(k) millionaire." Fine--but even at low inflation rates, a million dollars doesn't buy what it once did. Today's million dollars, for example, translates to $458,000 in 1985. For me, that makes a 401(k) millionaire who started 30 years ago a 401(k) 458-thousander.

Using real dollars greatly raises the bar, making the millionaire goal daunting for middle-income earners, and impossible for low earners. Then again, 401(k) plans aren't for the working poor. Even if low-income workers have access to a plan, which is by no means certain, they struggle to make meaningful contributions and are likely to remove their modest balances to meet daily needs. The 401(k)'s value is in proportion to the employee's salary, with the benefit receding to the point of invisibility by the time it reaches low earners.

That aside, the news is considerably better than one would think from an initial reading of Fidelity's data, which show only 72,000 401(k) millionaires from more than 13 million accounts. For one, those accounts are still growing. (Fidelity doesn't directly state that these 401(k)s are from active employees, as opposed to retirees, but as the average age of its millionaires is 59, that appears to be the case.) For another, as mentioned in the previous column, this measurement captures but a single account. If the employee has other 401(k) balances at other companies, and/or a spouse with an account, then the math can become much easier.

Let's do some back-of-the-Excel calculations. I'll assume a 2% annual real return on the 401(k) account, after expenses. (As a side note, I spent part of 1999-2000 attempting to convince corporate treasury departments that Morningstar's long-term forecast of 6% real on stocks and 3% real on bonds was not unduly pessimistic! Good times, that New Era.)

For wages, we'll use two projections of lifetime salary expectations, both expressed in today's dollars. The source is the Hamilton Project, a wing of the Brookings Institution. The first, more conservative projection is Hamilton's estimate of the year-by-year salary curve for the average college grad, assuming all majors. The second, more aggressive projection is Hamilton's estimate for economics grads--economics being a relatively lucrative major, although not the highest (trailing several engineering majors, for example).

These two paths, which I'll label as Median College and High College, give a flavor for the prospects of wage earners who are above the norm. As suggested earlier, those with average salaries aren't likely to become 401(k) millionaires, barring brilliant investment results, and those who make significantly below the average aren't likely to have much of a 401(k) plan at all. So the realistic pool will be drawn from those workers who are doing relatively well.

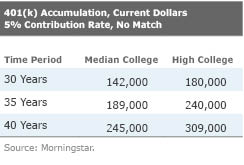

It's pretty clear that a 5% contribution rate won't get the job done. For confirmation, here's what the two paths generate, in today's dollars, with a steady 5% contribution rate and no company match. Even for a 40-year career, the economics major is at a modest $309,000. It goes down from there.

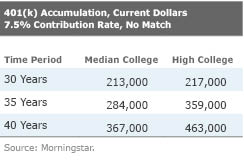

Kicking the contribution rate up a notch to 7.5% (no company match) doesn't work, either.

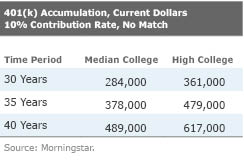

At 10% (once again, no match), the light begins to become visible. The 40-year projection for High College is more than $600,000, meaning that a married couple could cross the $1 million barrier if it had two wage earners at that level. Two earners working for 40 years at the Median College level, or two for 35 years at the High College level, would just about get the job done, too.

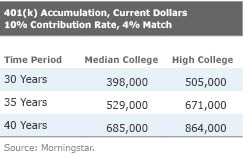

The final chart gives the deluxe scenario--not only a steep 10% employee contribution rate, but a generous 4% company match. Now the millionaire goal looks quite realistic for the married couple. The 40-year High College track gets there almost alone, needing only a modest addition from the spouse, and the 40-year Median College and 35-year High College paths make it about two thirds of the way.

Of course, the deluxe scenario is not the very top of the pyramid. At the pinnacle sits the truly wealthy, that is the employee who can afford to invest the legal maximum ($18,000 in 2015) into a 401(k) plan. With a 2% real return, that worker will hit the $1 million mark without receiving a penny of company match after 30 years and will be pushing $2 million for a full 40-year career. For somebody earning enough to hit the top marginal tax rates, becoming a 401(k) millionaire should be the norm, not the exception.

In summary, achieving a 401(k) million in today's dollars is 1) an easy task for the highest wage earners, 2) a reasonable goal for a high earner who gets some assistance from a spouse, and 3) possible for a married couple that consists of two moderately high earners. In the latter two cases, the presence of a company match is greatly helpful, but perhaps not strictly necessary if market returns are good, or if employees work a full 40-year career. Contributing at the high rate of at least 10% is required, however.

Young at Heart, But Not in the Mind Have you seen Cheryl's birthday puzzle? The sharper college kids solve it in their heads, in a couple of minutes. Those of us who graduated high school during the Carter years, not so much. That those same whiz kids can't make head or tails out of my columns--I've tested a few of them on my son's friends--is only partial solace.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)