The Dark Side of Vanguard's Success: A Reader's Argument

Was last week's column too benign?

Counter Point Don Andersen of Red Pine Investment Counsel wasn't enamored with last week's column, which stated that neither Vanguard investors nor the overall stock market should be troubled by Vanguard's record-breaking net inflows. In fact, Mr. Andersen found my article "grossly misleading."

I liked his email, for two reasons. First, in linking Vanguard's fortunes to the success of large-company U.S. stocks, Mr. Andersen expresses a common view. I do not believe that view to be accurate--but it is widely enough held so as to deserve further discussion. Second, Andersen corrects my discussion of how index managers affect the market's trading. He is right, I was not.

Begins Mr. Andersen:

The last time investors were piling into index funds was the 1995-99 period. We now know that was crazy because Vanguard 500 Index VFINX went down 38% in 2000-02, and the S&P 500 had its worst 10-year period ever from March 1999 to March 2009.

This paragraph requires some unpacking.

To start, Andersen assumes that Vanguard is synonymous with U.S. large-company stock indexing. Stating the matter generously, that's a substantial stretch. Roughly one third of Vanguard's $2.8 trillion in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (setting aside money market funds and not double-counting by including funds-of-funds) is in U.S. large-cap index portfolios. Another third is held by other flavors of index fund, and the final third is actively invested.

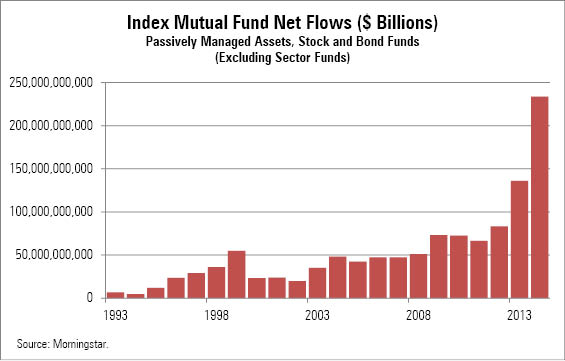

Andersen then assumes a relationship between the S&P 500's behavior and asset flows into Vanguard's index funds, a relationship that is difficult to discern. After all, index funds have sold well for 20 years now. While the 2000-02 slide temporarily discouraged stock buyers of all kinds, index-fund investors didn't stay down for long. By 2004, passive-fund inflows had almost returned to their 1999 peak. They have grown steadily and consistently since then.

Therefore, while it's possible to trace a hindsight connection between the popularity of index funds in the late 1990s and subsequent stock-market woes, as Andersen does, one can't do the same for the 2008 crash. Index funds took in more assets in 2008 than they did during the previous year, and more monies yet the following year. Whatever factors are to blame for 2008's plummet, index investors would not seem to be one of them. (If anything, index funds were a stabilizing influence.)

In short, there has been a lot more behind Vanguard's sales success than the accident of a blue-chip bull market. Among the reasons are discount pricing, clear communications, a cautious fund-launch approach, and unusually strict investment-risk controls. As a result of these practices, Vanguard has developed a reputation as a fund manager that takes unusually good care of its shareholders and that delivers on its promises. It is these attributes, not the providence of a given market sector, that have propelled the company to the top of the charts.

That said, I appreciate Andersen's contrarian mindset. Somebody who fully trusts a fund-industry leader is somebody waiting to be fleeced. Andersen is right to doubt the overall judgment of fund investors--and of bloggers who write about the industry. However, I believe for reasons stated in both this and the previous column, that this specific concern is unsupported.

You say that Vanguard avoids "unpleasant surprises." In other words, you're saying that 2000-02 and 1999-2009 were not "unpleasant surprises" or that a decline of 37% in 2008 was not an "unpleasant surprise" or that Vanguard also "failed 2008's test," as you said the American Funds did.

Vanguard's record sales directly refute this argument. Investors certainly regarded the down markets mentioned by Andersen as unpleasant surprises--but they did not lay the fault at Vanguard's door. After all, Vanguard had not promised them only bull markets. Nor did the company suggest that its funds would thrive during a downturn. Vanguard therefore met its shareholders' expectations. American Funds, in contrast, had publicly stated that active managers would perform their relative best when times were the worst. That argument was so strongly believed that even though most of American Funds' stock funds beat their benchmarks during 2008, the company was punished by redemptions, as investors judged the victory margins insufficient.

Fund investors may at times become overly enthusiastic, but their instincts are reliable. If they favor a fund company, it's because that fund company has delivered on its claims. Vanguard's greatest strength is that it, almost alone of fund companies, establishes expectations that it can consistently meet. In this business, less is indeed more.

Also, you comment on the obvious that Vanguard's index funds are passive, but then go on to say that they let "less-patient active managers push the stock around, then buy or sell against the market trend." That is flat-out untrue. Vanguard causes a lot of the upward movements with its buys ($219 billion in 2014, as you pointed out). You actually described what the really good and patient value-focused investors do, not what index funds do.

Last week's column suggested that active investors make stock-market prices, while index investors take them. That claim was, ahem, a substantial stretch--meaning that it was mostly wrong in the case of market-cap indexers. (It holds more true for value-oriented index strategies.) For the most part, as Andersen writes, the role of price-taker is filled by value investors, with growth investors making the prices and index funds landing somewhere in the middle. Yes, Vanguard's index managers try to trade against the market when possible. But their first task is to put their assets to work so their funds precisely track their benchmarks.

In theory, that still wouldn't make the rise of indexers destabilizing. After all, if there's a bubble in U.S. stocks, that bubble is presumably created by the volume of the inflows, rather than the method of investing. If indexers did not exist, surely other parties would invest the inflows and push up asset prices. Right?

Or so I thought. But then Morningtar's Kevin McDevitt reminded me of a 2012 Financial Analysts Journal paper by Rodney Sullivan and Morningstar's own James Xiong that raises a warning flag about spillover effects with market-cap indexing. In the words of the authors, the growth in market-cap indexing has led to "increased volatility" and "marketplace fragility." With respect to trading effects, Andersen's skepticism about Vanguard's growth--and the growth of market-cap indexing in general--would seem to be warranted.

1,070 Words I have never understood a single thing about bitcoin--why it exists, how it is created, why it is used, how it is valued. I have a general sense that there is some value in the currency's ability to bypass government scrutiny, but I have no idea how to determine whether the currency's current price accurately reflects that value.

My conclusion from this graph is that nobody else does, either.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)