What Happens When Vanguard Owns Everything?

The company is bigger than an 800-pound gorilla--and still growing.

Making History Vanguard is the most dominant fund company in history. It already manages the largest stock mutual fund in the world; it soon will run the largest bond mutual fund; and despite being a latecomer to the business of exchange-traded funds, it places a close second to iShares for new U.S. ETF sales over the past 12 months.

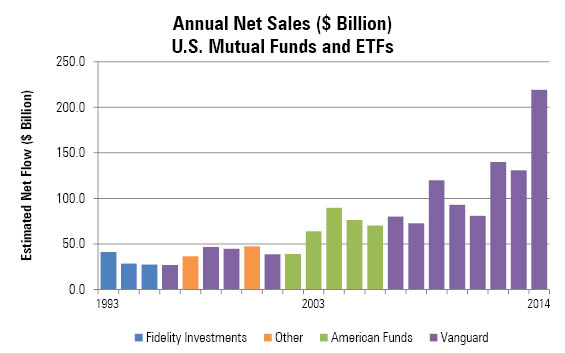

No fund company has ever enjoyed anything like Vanguard's 2014 net inflows of $219 billion into U.S. mutual funds and ETFs. Until American Funds managed the feat in 2003, no firm had ever even cracked the $50 billion mark.

Another way of putting the matter: Last year, Vanguard netted more assets than did all the leading fund companies combined during the New Era of 1995-2000.

Source: Morningstar.

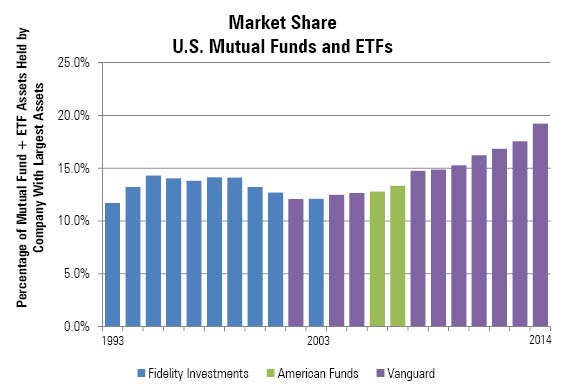

The seventh consecutive year of industry-leading sales has pushed Vanguard to record market share. Whereas previous leaders commanded between 10% and 15% of total industry assets, Vanguard ended 2014 at 19%. It almost certainly will be above 20% by the time that 2015 concludes.

Source: Morningstar.

There's never been anything like it.

The Implications Which begs two questions. What does the company's record-breaking success mean for Vanguard investors? Also, what does it mean for the financial markets overall?

The first answer seems straightforward: not much. Previous fund sales leaders almost immediately struck icebergs. Fidelity's domestic-stock funds ceased being extraordinary; Putnam and Janus (the two "other" companies in the first chart) sunk when growth stocks fell; and American Funds, booming because of the belief that it would beat bear markets, promptly failed 2008's test. But Vanguard is a different animal. Unlike those other firms, Vanguard has not implicitly promised to outperform the benchmarks. To maintain its brand and satisfy customers, Vanguard need only match the benchmarks and avoid unpleasant surprises.

That should not be a difficult task, as Vanguard was built for volume. Not only are most of its monies passively run, but those indexes are exclusively cap-weighted, rather than tilted to capture a "strategic beta." Consequently, Vanguard's passive funds need not make trades to re-align as the markets move. In addition, most Vanguard assets are in large, liquid securities, and even its active funds follow a mainstream, low-turnover approach.

The second answer is anything but straightforward.

Active managers like to talk about how the growth in cap-weighted indexes helps them by reducing competition. It's a compelling argument. Last year, this column discussed an academic paper that measured how much more difficult investing has become over the past 30 years because of the increase in professional active management. By the same logic, investing should become easier as indexing squeezes out active management.

Only, it's not quite that simple. The percentage of the stock market that is held passively has certainly risen--but stock prices aren't set by those who merely hold. Prices are set by buyers and sellers, most of whom continue to be active investors. Also, index funds would rather be price takers than price makers, meaning that they let less-patient active managers push the stock around, then buy or sell against the market trend.

Thus, even in a marketplace where most assets are controlled by index funds, active management will determine relative stock prices. (Absolute prices would seem to be a different story, as a flood of money into stock-index funds would presumably float all boats--and vice versa.) So the question becomes, are there fewer active managers than before?

Not that I can see. The fund industry is highly profitable, even for smaller players. While the fund business has been fully mature for 15 years now, and active management in recent years has been in outright retreat, that hasn't led to the mass shuttering of funds. Generally speaking, the funds that existed 10 years ago exist today. The same largely holds true with institutional investing. The big money managers who ran active institutional assets in 2005 are running active institutional assets today, too.

It's Not Over Yet The headline "What Happens When Vanguard Owns Everything?" is of course a cheat; Vanguard will never literally own the whole stock market. Nor, I suspect, will it ever have even a bare majority. But the notion that Vanguard in specific and indexing in general have grown too large has become quite common. (William Baldwin of Forbes recently addressed one such argument.) I think that concern is fruitless. Vanguard's situation is different than that of the industry leaders before it, and while indexing may eventually undercut itself through its own success, that time has not yet arrived.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)