Do Institutional Investment Consultants Add Value?

Results were noisy, but a new paper shows consultants overall struggle to add value through fund selection, writes Morningstar's John Rekenthaler.

Know Nothings?

Last week, The Economist profiled a forthcoming Journal of Finance paper--Picking Winners? Investment Consultants' Recommendations of Fund Managers--about the performance of institutional investment consultants. The headline: "Nobody knows anything."

Dramatically put, and a clever echo of William Goldman’s line about Hollywood. I’d be delighted to pen that headline. However, it is more than a slight exaggeration.

The authors--Tim Jenkinson and Howard Jones at Oxford and Jose Vicente Martinez at the University of Connecticut--obtained a database of recommendations for U.S. equity funds made by investment consultants who serve large institutional plans.

(The funds were large separate accounts, rather than registered mutual funds, which presented the authors with some difficulties, as separate account databases are not as clean as mutual fund databases. The authors did what they could--enough, I think, so that their general findings stand.)

Because the database pooled all recommendations without distinguishing either by individual or company, the professors could only compare the aggregate performance of recommended funds to the aggregate performance of all other funds. The study cannot measure the results of individual analysts or companies.

This is how I would summarize the paper--

Over a 12-year period, when selecting among a certain type of fund, the overall results of the funds recommended by a group of U.S. institutional investment consultants cannot be demonstrated to be superior to the overall results of funds that they did not recommend. It is possible that some of these analysts excelled at selecting that type of fund; it is possible that some or most or even all of these analysts excelled at selecting other types of funds; and it is possible that some or most or even all of these analysts excelled at tasks besides fund selection, such as asset allocation or liability matching.

That’s not quite "nobody knows anything."

The Economist narrows the subject to investment advice, such that "nobody knows anything" can be translated to "most investment advice doesn't lead to higher profits," and cites previous research on related topics, such as the recommendations of financial advisors, the performance of active mutual fund managers, and the Morningstar Rating for funds, or "star rating." The argument in essence is that many people spend much time and money attempting to get better investment results, without much aggregate success.

In that context, the claim works. While one can argue the details of those findings, there's no question that each study delivers the same general lesson: Beating the market is not commonplace. Picking Winners only touches a small part of the elephant, but its picture looks a lot like the pictures that were drawn before it.

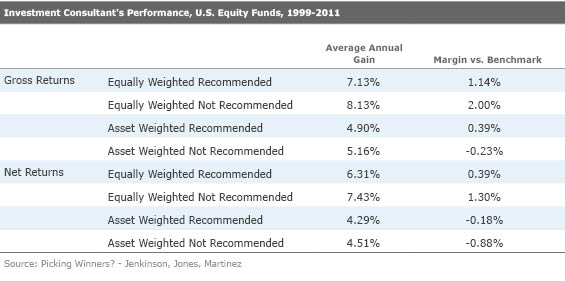

By the Numbers Here are the paper's key figures:

You should be confused.

For one, why have both flavors of the equally weighted portfolios crushed the asset-weighted portfolios? The answer: During the time period of 1999-2011, small-company stocks handily beat their large-company rivals. Because large-cap mandates receive more assets than do small-cap mandates, the large-cap portfolios tend to dominate the results of the asset-weighted calculation, and thus the asset-weighted figures trail the equally weighted numbers.

That’s an example of the subtleties that occur when combining results from different types of funds. It’s a useful endeavor, because otherwise a paper consists of table after table for each separate fund category, making it difficult to arrive at a conclusion, but it’s worth noting the challenge of interpretation. Such papers are not easy to decipher.

Similarly, what are we to make of the fact that the table’s returns destroy that of the Wilshire 5000? Over the time period, the Wilshire 5000 averaged 2.85% per year in total return. The table’s funds, whether recommended by the institutional consultants or not, made more than 4% after fees on an asset-weighted basis and from 6.3% to 7.4% on an equal-weighted basis. Could it be that institutional funds as a whole crush the benchmarks?

That would seem unlikely. We know from other research that active institutional funds tend to perform as retail mutual funds--perhaps slightly outdoing the benchmarks before costs and lagging after fees are considered. That makes sense as retail mutual funds and institutional funds draw largely from the same pool of major investment managers.

So, what is going on? Partially, it’s the small-company effect once again, as without question in the equally weighted group and probably also in the asset-weighted group the average stock held by the funds is smaller than the average stock in the Wilshire 5000. But that is not the entire story. The equally weighted group also handily beat the Russell 2000 small-company index (5.80%) and posted average annual alphas after cost (using the Fama-French four-factor model) of 0.39% for the recommended funds and 1.30% for the nonrecommended funds. If you believe those alphas, that’s a solid argument against indexing U.S. equities.

There is a slight mismatch in the comparison between the indexes and the funds, as the consultants' recommendations trickled in during February/March, while the index results are for calendar years. So very early 1999 shows up in the index results but not the consultants' record, with the reverse being true in early 2012. However, this is a minor difference, and it also does not alleviate the positive alphas recorded by the professors. It appears that either the institutional funds are good enough to refute The Economist's claim, or there's something else going on in the table that I haven't yet caught. Probably the latter.

(Thanks for slogging through this section [if you did]. My point was really not about this specific paper but rather about the difficulties of interpreting investment research. The nature of the beast is to summarize the behavior of many thousands, if not millions, of data points. It is a worthwhile task--but it requires very careful work from the authors to prevent inadvertent factors from affecting the output. And it’s very tricky indeed to spot those factors from the outside, without recourse to the full data set.)

Penny Wise, Pound Wise? The results are noisy, but the conclusion that investment consultants overall struggled to identify U.S. equity funds that would succeed in the future is not. Clearly, that's a tough way to make a living. My suggestion: Negotiate harder on fees. The paper found no difference in cost between recommended funds and those that were not recommended. Per the paper, investment consultants overall struggle to add value through fund selection. Perhaps they could more reliably add value by driving down costs on behalf of their clients.

Naturally, there’s the fear that pushing on fees will drive away the best managers and lead the consultants to choose the also-rans. That’s an understandable concern. However, per the research, on most performance measures the also-rans fared better than the preferred managers. The concern would seem to be overstated.

Groundhog Day In Chicago, we have our own way of telling when spring is arriving--when the newspapers resurface. Earlier this week, my wife discovered the Jan. 3, 2015, issue of The Wall Street Journal in a pile of melting snow. The paper contained a fine review of the year 2014. However, I would have preferred that it reviewed the year 2015; that surely would be the more valuable exercise.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)