Corporate Tax Reform's Winners and Losers

If tax reform talks get serious, investors should keep in mind who wins and who loses.

Scott Cooley is filling in for John Rekenthaler, who is on sabbatical.

Awaiting corporate tax reform is a lot like anticipating a Cubs World Series victory or the end of your child’s dance recital: It will be great when it occurs, but you can’t shake the feeling that people will be riding around in robot-chauffeured hovercraft long beforehand.

That said, in a political environment in which there is disagreement about just about everything, corporate tax reform is one of the few areas that has attracted bipartisan support. As such, investors should pay attention to tax reform developments, with an eye to determining which companies may be winners and which may be losers. For some firms, the impact—whether positive or negative—could total hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. If tax reform efforts appear like they might succeed, the market will likely adjust well before a bill actually becomes law.

Some background on a potential tax-reform bill: Among large portions of the Democratic and Republican parties, there is agreement that the U.S. headline corporate rate, which can reach 40% including state income taxes, is far too high in comparison with other advanced industrial nations’. Over time, in response to this high rate, companies have lobbied for—and received—various tax breaks that reduce their effective tax rates. In some ways, this is similar to what happens within the United States, when states that have uncompetitive business environments (I’m thinking of you, Illinois) dole out special benefits to companies to incent them not to move to states with lower taxes.

As a result, the United States has one of the world's largest percentage gaps between its stated corporate rate and the taxes actually collected. Aswath Damodaran, a professor of finance at New York University, estimates that this "tax code inefficiency" is among the 10 largest in the world, putting the U.S. in the company of nations such as Zambia, The Philippines, and Nigeria. That is not our desired peer group, and naturally this tax code inefficiency incents companies to hire lobbyists to promote even more special breaks. As Sen. Ron Wyden, D-OR, has said, "This insanely complicated tax code plays right into the hands of special interests."

Removing all these special tax breaks, in exchange for a more competitive tax rate, makes intuitive sense, so in general, everyone is for it. The problem is that some companies and industries benefit more than others from the current arrangements. So, like many things that sound great in theory, tax reform is trickier in practice.

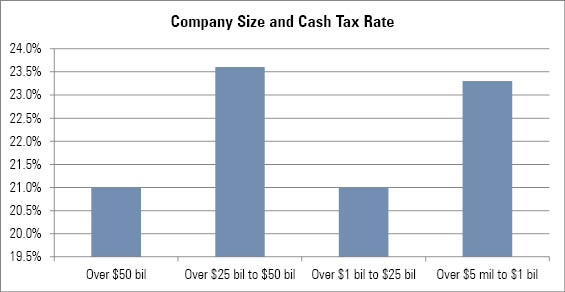

Although tax reform is often portrayed as a battle between tax-savvy large multinationals and smaller, highly taxed businesses--and, frankly, that is what I believed until running the numbers--the data do not bear that out. Using Morningstar’s equity data, I segmented companies by revenue levels and then examined their cash tax payments versus aggregate pretax income over a five-year period. Overall, after removing early-stage growth companies that had no revenue, I found that size was not a reliable predictor of companies’ cash tax rates, as shown below.

That said, certain types of large companies do have significant tax advantages. Using a different methodology, which relied on a single year’s reported earnings and reported income tax expense, Damodaran has found significant differences in effective tax rates based on industry. The lowest-taxed industries are not necessarily the same in each year, but in separate analyses, Damodaran confirmed the conventional wisdom that drug and technology companies tend to have relatively low rates, while retailers tend to have much higher rates.

Consider the difference in tax rates between

Both the president’s and Republicans’ tax reform plans envision curtailing tax preferences in exchange for a lower rate of 25%-28%, depending on the proposal. It is easy to imagine that such a plan, if enacted, might disadvantage Johnson & Johnson but give Wal-Mart a considerable profit and cash flow lift.

From investors’ perspective, then, it is worth thinking through what they own with a company like Johnson & Johnson. To be sure, they are getting a stake in a company with a suite of profitable life-saving drugs and widely used consumer products. But they are also buying cash flows that depend, in part, on the ability of Johnson & Johnson and other drugmakers to continue to extract tax benefits from the government. In the context of ongoing tax-reform discussions, does that tax-related cash flow stream perhaps deserve a lower multiple?

The truth is, no one know whether tax reform will happen this year; in two years’ time, when one party may control both the presidency and the legislature; or even later than that. But my bet is that the current complexity and uncompetitive rates of the current tax code will prompt action sometime in the next few years.

In fact, I’d wager my Cubs World Series pennant and robot-driven hovercraft on it.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CFV2L6HSW5DHTFGCNEH2GCH42U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7JIRPH5AMVETLBZDLUSERZ2FRA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YWKBIVULT5DGJEIGAJGBA6H5ZA.png)