Corrupt States Equal Investor Headaches

Corrupt states shortchange not only their students and hospitals but also their pensioners--and potentially their investors.

Scott Cooley is filling in for John Rekenthaler, who is on sabbatical.

Do states with a lot of corruption fund their pension plans more sparingly than those with less corruption? The answer appears to be yes: States with larger numbers of corruption convictions of public officials tend to have bigger unfunded pension liabilities. These Morningstar findings may have important implications for investors who buy states' debt obligations.

Scholars have known for a while now that countries with high levels of corruption pay a price for this dishonesty. Throughout the 1990s and early last decade, academics demonstrated that countries with lots of corrupt officials tend to have higher levels of income inequality, lower levels of private-sector investment, less international trade, and more currency crises--among many, many other negative consequences.

In 2014, two scholars--Cheol Liu of the City University of Hong Kong and John Mikesell of Indiana University--extended this research to the U.S. state level. In the June 2014 issue of Public Administration Review, they compared states' numbers of historical public corruption convictions with a number of state spending indicators. (Click here for the full report.) For the corruption indicators, they used the number of federal convictions of state and local government officials, as compiled by the Department of Justice in its "Reports to Congress on the Activities and Operations of the Public Integrity Section." This report details the number of convictions by state for the period 1976 to 2008.

Liu and Mikesell found that in a number of key ways, more-corrupt states behave differently than less-corrupt states. According to the authors, "States with higher levels of corruption are likely to favor capital, construction, highways, total salaries and wages, borrowing, corrections, and police protection, at the expense of social sectors such as total [spending on] education, elementary and secondary education, health, and hospitals."

In short, more-corrupt states tend to borrow more and spend more on areas from which they can extract value, and less on social services. To take one example, corrupt states spend more on large infrastructure projects, on which public officials can more easily obtain kickbacks, and less on education. Over the period of their study, 1997 to 2008, Liu and Mikesell estimated that relative to states with average corruption levels, the 10 most corrupt states essentially wasted an extra $1,308 per capita.

Although Liu and Mikesell identified many areas in which corrupt officials shortchange their states' residents, they did not look at one key fiscal lever: pension funding. In Illinois and many other states with high levels of corruption, the opacity of pension-funding calculations would make it easy for public officials to shortchange public workers' pensions and direct state resources elsewhere.

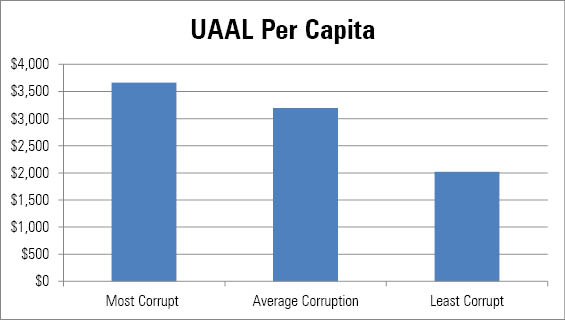

I further extended this research by examining historical corruption levels and pension funding. In 2013, Morningstar released a report on state pension-funding levels that included a measure of per-capita pension underfunding, called unfunded actuarial accrued liability (or UAAL). In simple terms, I bucketed states into thirds, according to their levels of corruption convictions from 1976 and 2008, and averaged their UAALs. As expected, the most corrupt states tended to have the highest per-capita unfunded liabilities.

State Corruption and Unfunded Pension Liabilities

Sources: Morningstar, Department of Justice.

(For the more statistically inclined, I also ran a bivariate regression using historical corruption as the independent variable and UAAL per capita as the dependent variable. The resulting p-value of 0.024 easily meets the test for statistical significance, indicating that it is relatively unlikely that chance accounts for the positive relationship between corruption and per-capita pension underfunding.)

It is important to note that this relationship, while statistically significant, is not completely linear. For example, Tennessee scores poorly on corruption measures but boasts an exceptionally strong pension-funding level. By contrast, New Hampshire is one of the least corrupt states but has an above-average unfunded pension liability.

From an investor perspective, these findings suggest that, at least at the margins, variation in corruption levels may have an effect on which states' bond issues are the most desirable. True, corrupt states tend to be less well-managed, which means their bond ratings often already reflect the negative consequences of corruption. But as Liu and Mikesell's research shows, there are a multitude of ways that corrupt officials can game government budgets to their advantage. It is almost certain that many of these corrupt practices are hidden from the public eye, and therefore are difficult for ratings agencies and even sophisticated investors to assess.

For an investor viewing two apparently similar debt issues, investing in the obligation of the less-corrupt state may be a good tiebreaker.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CFV2L6HSW5DHTFGCNEH2GCH42U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/7JIRPH5AMVETLBZDLUSERZ2FRA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/YWKBIVULT5DGJEIGAJGBA6H5ZA.png)