A Big Band-Aid, but No Cure for Europe

The ECB did what it had to do this week, but quantitative easing won't solve Europe's fundamental problems.

The biggest news this week was the European Central Bank's announcement of a very large and very long program of quantitative easing. After tiptoeing around the issue for more than a year, the ECB decided to implement a massive bond-buying program that matches the scope of the United States' QE3 program.

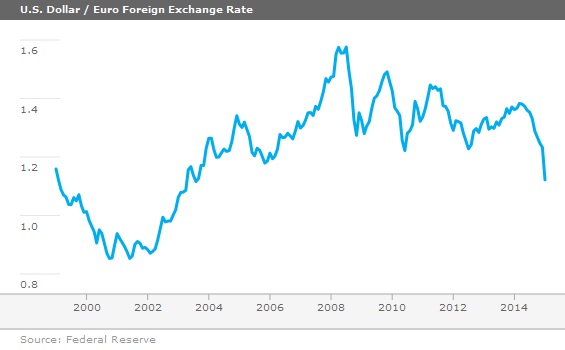

With much of the action widely anticipated, the reaction this week was relatively muted. Still, the euro and worldwide interest rates had already been falling for months in anticipation of this well-telegraphed program. Remember, even in the United States interest rates fell dramatically while QE was in the rumor stages, and remember that rates began to move up shortly after the formal bond buying was started.

The economic news this week ultimately wasn’t momentous in either direction. Housing data remained stuck in neutral, but that is often the case during the holidays and bouts of cold weather. It will probably be at least springtime before we can tell if lower rates and better employment data will help this industry regain its mojo.

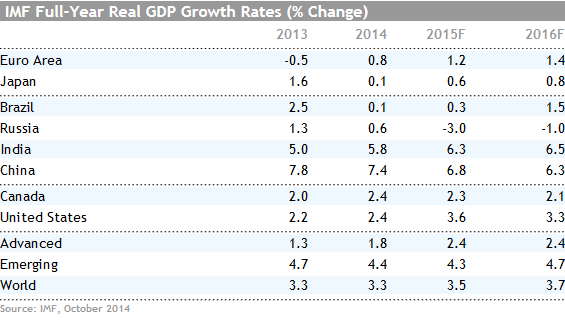

IMF world growth forecasts showed their typical pattern of decline, with even the normal optimism about some of the out years flagging. Just as U.S. growth has been stuck in its 2.0%-2.5% rut (although the IMF expects a huge breakout in 2015--don't hold your breath), the world data can't work its way out of 3.3%-3.5% trend line growth rate. Speaking of ruts, the flash world purchasing manager data from Markit was statistically unchanged month to month in all of the major markets. The fact that things didn't get any worse was cold comfort for investors when the data was released Friday.

Performance-wise emerging-markets equities did the best this week, gaining more than 3% as they benefited from the QE announcement out of Europe in addition to better-than-expected manufacturing data and GDP results. Europe, the United States, and the rest of developed-world equity markets grew between 1% and 2%. U.S. interest rates were little changed even as European rates continued their declines. Commodities continued their losing ways, falling over 1% yet again this week.

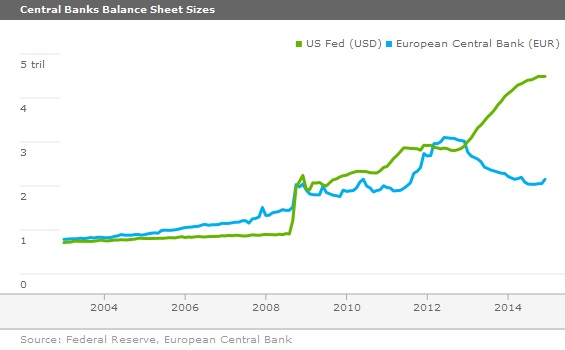

ECB Quantitative Easing Program Exceeds Expectations The much-anticipated ECB quantitative easing program was finally announced on Thursday, and it didn't disappoint, at least in terms of size and scope. Some of the finer details are still sketchy. What we do know is that it is a massive program: $69 billion per month for the 20 months between March 2015 and September 2016, or about $1.4 trillion. For some perspective, the latest U.S. QE program was for $85 billion per month at its peak. U.S. QE 3 extended from September 2012 to October 2014. The Federal Reserve balance sheet currently stands at about $4.5 trillion, and the ECB's balance sheet is currently about $2 trillion. That gap is clearly about to close. The European and U.S. economy are approximately the same size in terms of GDP.

QE Lets Central Banks Take More Direct Control of Long-Term Rate A quick reminder of the mechanics of central banking and what QE really means: Central banks have historically used their direct control of short-term interest rates to member banks (and reserve requirements) to influence the economy and inflation. They also used purchases of very short-term securities to help move inflation into target ranges.

Central banks almost always just had direct control of very short-term interest rates. However, the more important long-term rates usually (though not always) moved in concert with those well-controlled short-term rates. By moving interest rates, central banks hoped to encourage/discourage business activity to keep inflation in desired ranges. Rates were moved up when economic activity heated up and inflation had begun to rear its ugly head. Once the economy slowed and inflation returned to desired ranges, the Fed would lower rates. For decades, rate changes were exceptionally effective, with housing- and auto-related activity accelerating quickly when rates declined and stopping dead in their tracks when rates increased.

But things have been different the past few years, with short-term rates not always moving long-term rates because of some complicated supply and demand issues. Furthermore, with deleveraging and short-term rates already near zero interest, the Fed and other central banks seemingly lost the ability to stimulate the economy further. Central banks, led by the United States, took matters more directly into their own hands and began to try directly influencing long-term rates. They did this by purchasing government bonds with ever-increasing maturities and even began to directly purchase mortgages. This buying of longer-term bonds is what is meant by quantitative easing. It has helped economic activity some, with housing and autos responding to the lower rates. The conventional mechanisms were working some, but not enough. Autos and housing weren't as influential on the economy as they had been in the past. And tight lending conditions--and not mortgage rates--were what was constraining the housing market.

QE Offers New Mechanisms to Bring Up Inflation Rates and the Economy However, U.S. quantitative easing kept the dollar relatively weak (low rates encouraged foreigners to sell their U.S. bonds and move the money to another country), which helped exports. And the extra money created by the Fed flowed into other assets, boosting asset prices.

Rising asset prices had some big knock-on effects for the economy. Most prominent were so-called wealth effects. While consumers are conservative in spending their stock and housing market gains, they do manage to spend 3%- 5% of their gains over the next one to five years. Although the wealth effect and a cheaper dollar had previously aided economic growth, they were now the primary mechanism that led to an improving economy with the latest round of quantitative easing.

United States Takes the Lead in Widespread Adoption of QE The United States was the first to really grasp the importance of the new mechanisms and the importance of quantitative easing. That at least partially explains why the U.S. economy has outperformed the European and Japanese economies over the past several years. The Fed's dual charter (that includes both inflation control and labor market stability) and the truly centralized nature of U.S. banking made implementing quantitative easing much simpler than anywhere else in world.

Both the ECB and Individual National Banks Will Do the Actual Bond-Buying That brings us back to Europe's latest plan. Technically, a great deal of the bond-buying will happen on the national and not the ECB level. National debt has to be bought by national banks. European institutional debt, however, will be bought by the ECB. This avoids the issue of the central banks buying individual country debt, which is technically prohibited by the ECB charter.

ECB QE Will Have Its Greatest Impact via Exchange Rates With rates already negative in some markets, lower interest rates aren't likely to drive a lot of new demand. And housing and autos, the most interest sensitive sectors, are smaller in Europe than in the United States. In addition, business investment has been particularly soft and lower rates could help some, but with rates already so low, we are not expecting a new boom in European investment. Stocks and bonds also are not as widely owned by individuals in Europe as they are in the U.S., which means that wealth-effect gains in Europe are likely to be more muted than in the United States.

However, the easing program and the flood of new euros it creates will drive the euro exchange rate lower. The market has already well anticipated this with the euro falling from 1.58 to the U.S. dollar at its high to 1.12, a decline of 29%. In Europe, the impact of a falling currency will be potentially huge. Exports account for over 25% of European GDP, almost double the level found in the United States, about 14%. By the way, almost half of those goods are related to heavy machinery and transportation equipment.

So, if the euro remains low enough for long enough, the lower exchange rate could be a big boost to Europe. However, I do caution that a lot of the machinery market is looking soft, exchange rate or not, as the demand for worldwide commodities (which require a lot of machinery to process) remains in the drink.

QE Will Not Solve Europe's Fundamental Problems, but It Is a Decent Size Band-Aid for Now Traders, newspapers, and pundits love QE. Traders salivate at the mere whisper of the initials QE. Because QE appears to have worked so well in the U.S., market participants are extrapolating any QE announcement from around the world to mean a better economy and better market action.

But I don't think QE was the entire reason the U.S. economy has done so well on a relative basis. The U.S. banking system was completely overhauled in 2008 and 2009 and now U.S. banks are in better shape than most other major systems around the world. The U.S. oil boom didn't hurt, either. And at the end of the day, the short-term federal budget has shrunk to below long-term averages. How all these positive things came to be isn't very pretty and doesn't exactly represent democracy at its finest.

However, at least the U.S. ultimately did take action on several structural fronts beyond relying purely on QE to save the day. Europe has not followed suit. Labor markets in much of Europe are way too rigid, partially explaining an unemployment rate of over 11% versus half that rate in the United States. Tax policies, especially in France and Italy, remain huge issues. And Germany has done little to help stimulate internal demand even as it reaps the benefits of stronger exports. The banking system also remains weighed down by too much leverage in many cases. The last thing that some of these banks should be doing is making more loans, but that is exactly what the ECB seems to be encouraging.

Nevertheless, with politicians and legislative bodies sitting on their collective hands, someone needed to do something. And the ECB has stepped up to the plate with an action plan that should at least put a temporary Band-Aid on the problem. It followed through and did what it had to do. And now I can crawl out from beneath my desk, where I had been hiding, to make sure the ECB didn't flinch at the last minute. Let's hope the individual governments follow through with actionable plans of their own.

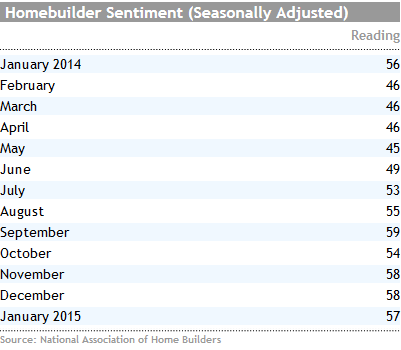

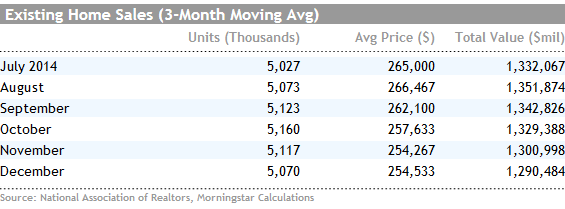

Housing Data Going Nowhere Fast Housing was one of 2014's biggest disappointments, and this week's data from December and January didn't seem to show much new strength. Homebuilder sentiment was down just 1 point in January compared with December while both existing-home sales and housing starts were up statistically insignificant amounts.

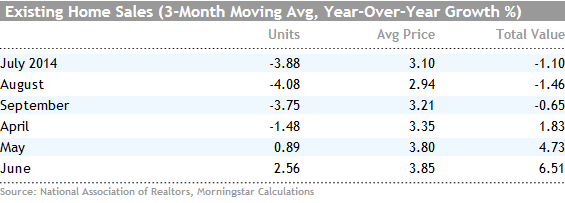

2014 as a whole is a year that a lot of housing-related industries would just as soon forget. Existing-home sales were down 3% for the year, even worse than the expectations for a flat year. Housing starts were disappointing for the year, but at least they managed an 8% gain, with most of the improvement coming in the multifamily sector. Builder sentiment was flat at 57 for December in both years.

Affordability, stagnant incomes, student loans, and tight lending were all big detractors to 2014 growth in the housing market. Existing-sales growth rates in 2014 were hit hard because of super-strong 2013 numbers that were the result of an interest rate panic in the middle of 2013. New homes had the additional weight of an ever-widening gap between the price of a new home and the much cheaper existing home (the gap is now as much as $75,000-$100,000). When the last house is counted, I don't think housing added or subtracted from the fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter GDP calculation.

With better employment and income levels expected in 2015, we are hopeful that many housing sales metrics could improve by 10% or more this year. Housing should also be a meaningful contributor to the GDP calculation in 2015.

Builders See No Boom and No Bust Looking at the monthly data, the sentiment data isn't suggesting a quick rally in the housing market. Sentiment peaked at 59 over the summer and has bounced around modestly lower numbers in the back half of the year.

Traffic data, which is considered the best and most objective indicator of future housing results, fell from 46 to 44. The future sales indicator fell from 64 to 60. The current sales activity marker was unchanged at 62. As I said, not a lot of new information to hang our hats on.

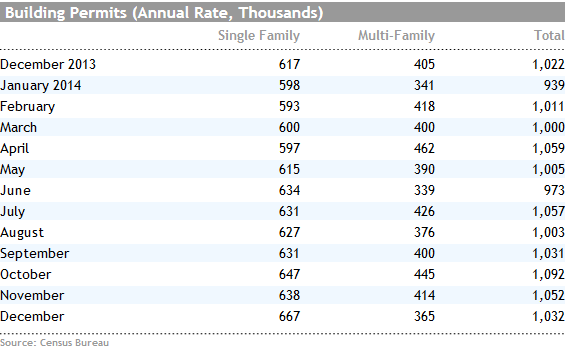

Monthly Starts Look Up as Permits Fade Overall housing starts increased by 4.4% between November and December to a more acceptable 1.09 million level, exceeding expectations. An unusually warm December may have provided a small boost to the results.

The 1.09 million rates compares favorably with the full-year 2014 run rate of 1.01 million units. In fact, the December figure was the third best of the year. The single-family starts did particularly well in December, jumping to their very best level of the year.

Given that single-family homes have a bigger impact on the economy than an apartment building, this was the single best piece of news out of the housing sector in some time. Still, I caution that this is just one month. However, single-family permits also looked better even as permits in the multifamily sector began to fade. I generally prefer to look at the permits data because it is less affected by weather and provides new data sooner, as permits are required before a start can happen in most jurisdictions. The slower multifamily data comes as a bit of a surprise given collapsing vacancies rates and meaningfully higher rents in some areas. Maybe the big December drop is a statistical fluke that will be reversed next month.

Existing-Home Sales Pick Up Some of What Was Lost in November Existing-home sales made a slight dip below the 5 million level in November to 4.92 million units. The November number didn't seem to mesh with other housing data, suggesting that December would look much better. Indeed, December was better at 5.02 million units, but investors had been hoping for 5.08 million units. Full-year results were 4.93 million units sold compared with 5.1 million units a year ago, representing a 3% decline.

Like all the housing data, the results look relatively stagnant with no signs of a big collapse or a big rally. Unfortunately, relative to the third quarter, existing-home sales were down in the fourth quarter in both dollars and units. This will potentially make housing a detractor instead of an adder in the fourth-quarter GDP calculation.

Even our year-over-year averaged growth rates show relatively lackluster results. At least we have the unit trend data showing steady improvement since August.

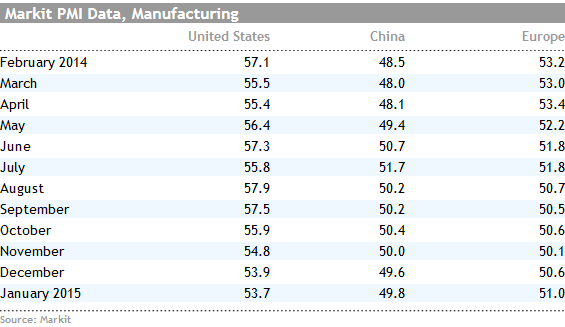

Manufacturing Data Not Moving Statistically, PMI readings for Europe, China, and the United States were virtually unchanged. The U.S. was down a smidgen but still meaningfully higher than Europe and China, which were up just a touch. With all the recent tumult, the PMI numbers could have been a lot worse.

I wrote last week that the United States had a barn-burner of a year in 2014 because of near-perfect alignment of the stars. We also mused that the best might just be behind the United States as auto sales growth slowed along with exports and any products related to oil production. The PMI data is painting a similar picture as the U.S. reading is now at its lowest level in 12 months, and the pattern has been straight down since August. However, a reading significantly above 50 still indicates growth.

China's numbers were still in decline at 49.8, but at least the number looked better in January than December. Like China's fourth-quarter GDP growth rate of 7.3%, the number wasn't great but managed to do better than already-diminished expectations. Both numbers garnered at least a small sigh of relief from market participants. The China-related portions of the report were just OK while the export-related portions of the report were decidedly more bullish, perhaps because of strength in the United States.

Europe's numbers made a more meaningful improvement from 50.6 to 51.0. However, Markit statisticians were quick to point out that this type of level correlated with annualized GDP growth rates of just 0.8%--not something to jump up and down about just yet. Continuing the trends of recent months, the peripheral European countries outperformed the core countries of France and Germany.

U.S. Shines as World Growth Rates Slashed Again in IMF's New Forecast The IMF has been consistently too optimistic about worldwide growth rates over the past five years. A slowing Chinese growth engine, unfavorable demographics, and falling commodity prices have all contributed to the missed forecasts. The most recent forecast shows that the world will continue to be stuck in its 3.3%-3.5% growth rut through 2015. The 2015 world growth rate would have been even worse without the boost from an accelerating U.S. economy. The IMF sees world growth accelerating modestly in 2016 to 3.7%; however, considering their typically cheerful projections, it is highly uncertain whether this higher rate will actually materialize.

Durable Goods, Pending Home Sales, Fed Statement, and Real GDP on Tap for Next Week The GDP number next week will probably be the most important of the lot. I believe that fourth-quarter GDP growth will fall in the 2.5%-3.0% range, down sharply from the somewhat anomalous 5% rate of the third quarter. Exports and housing are likely to be detractors in the fourth quarter after being significant adders in the third quarter. Business investment is likely to grow slower in the fourth quarter, too. Though most economists are expecting a significant slowing in fourth-quarter GDP growth, some of my clients still seem a little shocked that the GDP growth rate could be cut in half in the fourth quarter.

I suppose seeing how the media reacts to and reports this number might be more interesting than the number itself. Will they characterize it correctly as a return to normal? Or will they write this as a "Beginning of the End" story, with growth rates collapsing and the worst yet to come given slumping numbers from the oil fields and falling exports? Or will they focus on the year-over-year growth rate for the full year, which should come in at 2.4%, little changed from the 2.2% rate of the prior year?

We are sticking with our analysis of relatively slow growth and little change in speed or direction of the economy once any potential funny business is stripped out of the reports. That is, 2.4% growth for 2014 and in the range of 2.0%-2.5% in 2015. As much as I love low gas prices, I don't think they will be the rocket fuel to drive the economy back into the good old days of 3%-4% growth.

Durable Goods: Let's Just Wait and See Based on my forecasts of a slowing manufacturing economy in 2015, I suspect that durable goods orders will deteriorate at some point in the near future. Forecasts for December are all over the lot, all because of Boeing. Some forecasters are using pure trend line analysis and are hoping for a relatively positive report. Others who are merely counting Boeing plane orders are also expecting relatively benign results. Those adding up the value of the planes sold by model type are quite bearish with expectations of large headline declines after normal seasonal factors are applied. I will remain focused on year-over-year core numbers, averaged, excluding those pesky airplanes. Category analysis may prove useful, too.

Pending Homes, Well, Pending Existing-home sales have missed modest forecasts for two months in a row, and we will be looking at pending homes to help us guess if the downward trend can be broken. Given the above-average weather in December, I am hopeful that pending home sales will look better, which should translate into better existing-home sales in January and February.

Fed News Likely to Be Uneventful Next week the Fed will be the central bank under scrutiny with a new policy statement due on Wednesday. This is not one of the "major" meetings with a new economic forecast and a full press release. I suspect that recent events, including actions on the Swiss franc and the ECB, may make the Fed leery of rocking the boat any further, so soon. Higher initial unemployment claims and oil field-related issues may give it the fig leaf it needs to leave the language in past statements little changed. Of course, all bets are off if the Fed sees any red flags in its advance copy of the fourth-quarter GDP report that comes out less than 48 hours later.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)