The Attack on Shareholder Value

Can a company be measured solely by its stock returns?

The Challenge Has Been Issued For four decades now, the corporate raiders have ruled.

In the 1970s, U.S. stock investors became carnivorous, as the new breed of corporate raiders was hatched. This species, unlike previous institutional investors, did not believe in live and let live. Rather than passively perch on the shoulders of a company and share in its spoils, the raiders instead sought an active role. They would direct the host in its hunting--and if the host did not listen, the raiders would capture it, tear it apart, devour it, and move on to new prey.

Time moved differently for corporate raiders than for their predecessors. The raiders hoped to own a stock for months, not years (and certainly not decades). Consequently, they cared little about most CEOs' goals. Improving product quality, growing market share, retaining employees … those were beside the point. What really mattered was for the stock price to rise. What really mattered was the creation of shareholder value.

The emergence of red-blooded capitalism, as it was termed, was hailed by free-market defenders. The Wall Street Journal and Barron's wrote glowing accounts of how the raiders turned fat and happy corporations into the lean and hungry. Business-school professors were equally delighted, as the roots of shareholder value lie in academic theory. The doctrine of the outsiders quickly became the accepted norm.

Although few corporate raiders now exist, their legacy lives on with activist hedge funds, MBA curricula, and executive-pay plans. Shareholder value never fully took hold in other countries--more on that to come--but in the U.S. it has reigned nearly unchallenged. Unions have protested, to be sure, but few within the investment world have argued against the proposition of measuring performance by stock price.

The counterattack, however, has begun.

In truth, that attack has always existed--outside the U.S. Although shareholder value gained some traction in other Anglo countries, it did not get far in continental Europe (or Japan). Even in the United Kingdom and Canada, two of the stronger adherents, the approach was never adopted as enthusiastically as in the U.S.

The Shareholder Value "Myth" Now, however, the criticisms are coming from within. Among the loudest shots have been fired by Cornell Law professor Lynn Stout, in The Shareholder Value Myth: How Putting Shareholders First Harms Investors, Corporations, and the Public. Stout argues that her business-school cousins have it wrong across the board--legally, mathematically, and empirically.

Legally, she states, “it is important to note that shareholder primacy theory [that is the shareholder-value proposition] was first advanced by economists, not lawyers. This may explain why the idea that corporations should be managed to maximize shareholder value is based on factually mistaken claims about the law.” Stout disputes the common notion that “shareholders ‘own’ corporations.” Rather, she writes, corporations are legal entities that own themselves. Shareholders, bondholders, suppliers, and employees “stand on equal footing”; they are all contractors with the firm, possessing limited legal rights.

Further, she argues, shareholders of healthy companies are not the residual claimants of all corporate profits. They are residual claimants if the company expires, as they receive what remains after other contract holders are paid. But outside of bankruptcy court, "the legal entity is its own residual claimant, meaning the entity is entitled to keep its profits and to use them as its board of directors sees fit." The board may choose to pursue any legal objective, "including taking care of employees and suppliers, pleasing customers, benefiting the community and the broader society, and preserving and protecting the corporate entity itself. Shareholder primary is a managerial choice--not a legal requirement."

On math, Stout writes “Milton Friedman and other late twentieth-century academic economists were obsessed with optimizing: picking a single objective, then figuring out how to maximize it.” This approach simplified their calculation, she states, but at the cost of accuracy. The real task of a corporation is not to make one stakeholder supremely happy, but rather to satisfy several objectives simultaneously. As an analogy, “If people made decisions by optimizing, we would not find ourselves debating between taste, calories, and nutrition in choosing what to eat for lunch.”

As for empirical results, she cites several academic studies that examined the stock-market results of companies with shareholder-unfriendly policies (for example poison pills that protect corporate management). Shareholder-value theory predicted that those firms would have performed poorly, but in aggregate they did not.

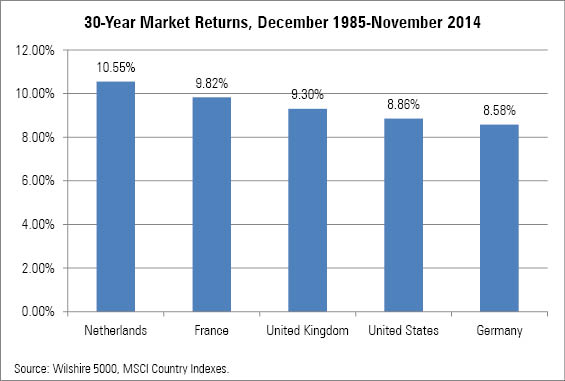

The Markets Say ... Another way of viewing the matter is to compare the results of the U.S. stock market with those of the major European marketplaces. As previously mentioned, shareholder-value theory has been most influential in the U.S., somewhat less so in the United Kingdom, and largely ignored in continental Europe. Can this pattern be seen in the 30-year market returns?

Apparently not.

Over the past two years, the barrage has intensified. Both The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times have published articles criticizing shareholder value, the Times on multiple occasions.The discussion has gone thoroughly mainstream.

It also is making its way into money-management circles--an audience that historically has been among the strongest supporters of shareholder value. Earlier this month, James Montier of GMO published a white paper calling shareholder value "the world's dumbest idea." He assembles several charts in support of his contention that the practice damages the long term by overemphasizing the short term. Montier's recommendation is the same as Stout's: acknowledging that companies have multiple constituencies.

Summary Two questions: Will the backlash strengthen and, if so, what might that mean for investors?

For the first question, a tentative yes. The current orthodoxy has been in place for several decades. While it has not been proved wrong, neither has it made a convincing case for itself. Yes, many particularly slow-growing and asset-rich companies have been transformed through the notion of shareholder value--often with excellent benefits for stock owners (although not necessarily for those companies' employees). But it's not clear that the typical firm has fared better by having its managers constantly measured by stock-market returns. Thus, the questions will continue.

As for the second question, I suspect the answer is "not much in aggregate." Some companies likely will perform less well, as their managements relax when not having their feet held to the fire. Others likely will meet Montier's expectations by improving their prospects through increased investment, as managements will be willing to take more chances on long-term investments. Overall, then, I would expect that a change in the shareholder-value mind-set would not much affect U.S. stock-market averages.

It is possible, however, that it might improve the prospects of active mutual fund managers. If corporate managers are afforded more freedom to reward (and hire) employees, increase capital investment, and/or purchase more businesses, then they have more rope with which to either create something of value or hang themselves. Perhaps the astute fund manager will be able to distinguish between the bad and good corporate managements.

Perhaps. It's only a wink of hope, but after the annus horribilis for active managers that was 2014, a wink is as good as a nod.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)