Want to Boost Your Retirement Income? ‘Guardrails’ Could Help

The Guyton-Klinger method aligns withdrawals with portfolio performance—but without extreme cash-flow volatility.

Dynamic retirement-spending strategies, which vary retirees’ cash flows based on how their portfolios have performed, can help retirees spend more from their portfolios than spending strategies that aim to supply the same real withdrawals year after year.

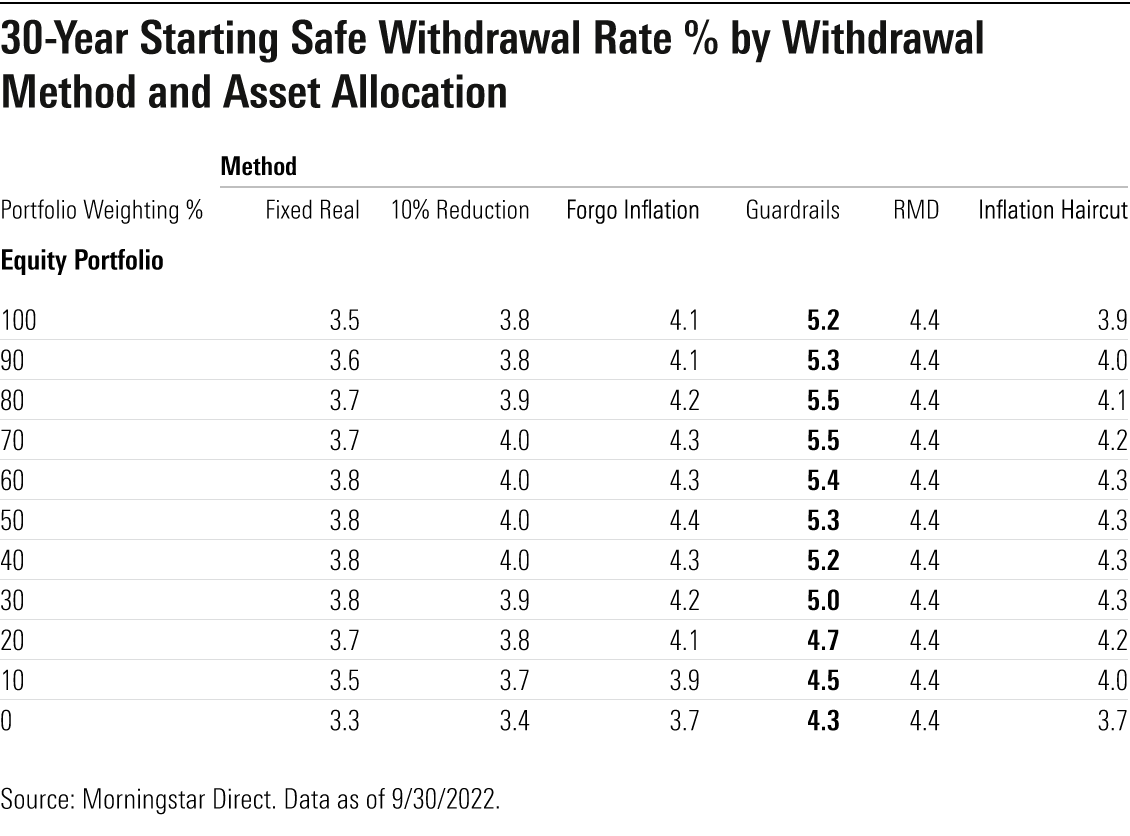

Indeed, in research that Jeff Ptak, John Rekenthaler, and I conducted on safe withdrawal rates late last year, every one of the dynamic strategies that we tested allowed for a higher starting safe withdrawal rate than would be the case with a static withdrawal system. Whereas our “base case” system of fixed real withdrawals pointed to a 3.8% starting withdrawal percentage as sustainable for a balanced portfolio over a 30-year horizon, the starting safe withdrawal rates for variable strategies ranged from 4% to 5.3%.

The natural question is: Which of the dynamic strategies allowed for the highest initial withdrawal rate? The answer is the so-called guardrails strategy, developed by financial planner Jonathan Guyton and computer scientist William Klinger. Guardrails offered the highest starting withdrawal rate and the second-highest lifetime withdrawal rate of any of the systems that we tested. But as effective as the Guyton-Klinger system is at boosting retirees’ cash flows, it isn’t not without trade-offs. As with all dynamic strategies, volatility in year-to-year cash flows might be unwelcome, especially when it dictates spending cuts. Additionally, retirees employing a guardrails system will generally have lower residual balances after 30 years than will be the case for spending systems that target a fixed real payday throughout retirement. In other words, retirees get to spend more during their lifetimes, but there will tend to be fewer leftovers for bequests.

How It Works

The guardrails attempt to deliver sufficient—but not overly high—raises in upward-trending markets while adjusting downward after market losses. In upward-trending markets, in which the portfolio performs well and the new withdrawal percentage (adjusted for inflation) falls below 20% of its initial level, the withdrawal increases by the inflation adjustment plus another 10%.

To use a simple example, let’s say the starting withdrawal percentage is 4% of $1 million, or $40,000. If the portfolio increases to $1.4 million at the beginning of Year 2, the retiree could automatically take $40,000 plus an inflation adjustment—$41,136, based on a 2.84% inflation rate. Dividing that amount by the current balance—$1.4 million—tests for the percentage. $41,136 is just 2.9% of $1.4 million. As that 2.9% figure is 27% less than the starting percentage of 4%, the retiree qualifies for an upward adjustment of 10%. The new withdrawal amount becomes $45,256—the scheduled amount of $41,136 plus the additional 10% of $4,120.

The guardrails apply during down markets, too. Specifically, the retiree cuts spending by 10% if the new withdrawal rate (adjusted for inflation) is 20% above its initial level. For example, let’s say the retiree withdrawing 4% ($40,000) of the $1 million portfolio in Year 1 immediately strikes an investment iceberg, losing 30% of the portfolio value in Year 1. The portfolio drops to just $700,000 at the beginning of Year 2. The Year 2 withdrawal would be $41,136 on a pretest basis. But because $41,200 from $700,000 is a 5.9% withdrawal rate—more than 20% higher than the initial 4%—the retiree would need to reduce the scheduled $41,136 amount by 10%, to $37,016.

Importantly, the Guyton-Klinger method scraps the cutback rules (following portfolio declines) in the final 15 years of retirement, in acknowledgment of the fact that weak returns are especially dangerous early in retirement but less so later on. Guyton-Klinger also includes some portfolio-management rules related to the spending of various assets—for example, if the equity allocation exceeds its target allocation because of strong performance, the excess equity exposure is sold and added to cash. However, for this exercise, we focused exclusively on changes to the withdrawal rate rather than including the portfolio-management rules.

The Payoff

The benefit of adhering to those rules is the highest starting safe withdrawal amount of any system we tested. For a 50% equity/50% bond portfolio, the average safe starting withdrawal rate for a 30-year horizon with a 90% probability of success was 5.3%. (In this context, we define “success” as not running out of funds by Year 30). And for portfolio heavier equity allocations, the allowable starting safe withdrawal amount was even higher: 5.6% for portfolios with 80% in stocks, 5.9% for 90%, and 6.3% for all-equity portfolios!

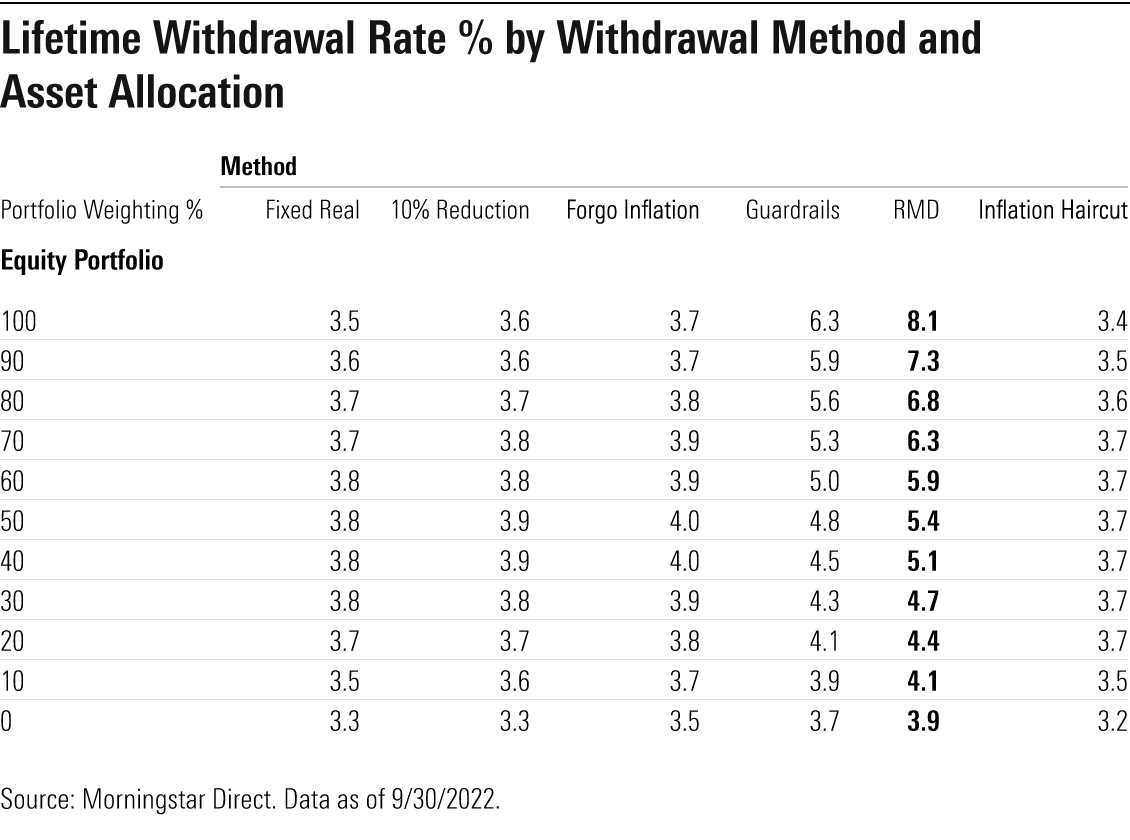

In addition to the highest starting safe withdrawal percentage, guardrails had the second-highest lifetime withdrawal rate of any system we tested—second only to the RMD method. Guardrails provided for a 4.8% lifetime withdrawal rate for a 50% equity/50% bond portfolio and above 6% for a 100% equity allocation. Like an RMD-based approach, the guardrails system was highly efficient, as the periodic course corrections help the retiree consume more of the portfolio in up markets but not too much in bad ones.

The Catch(es)

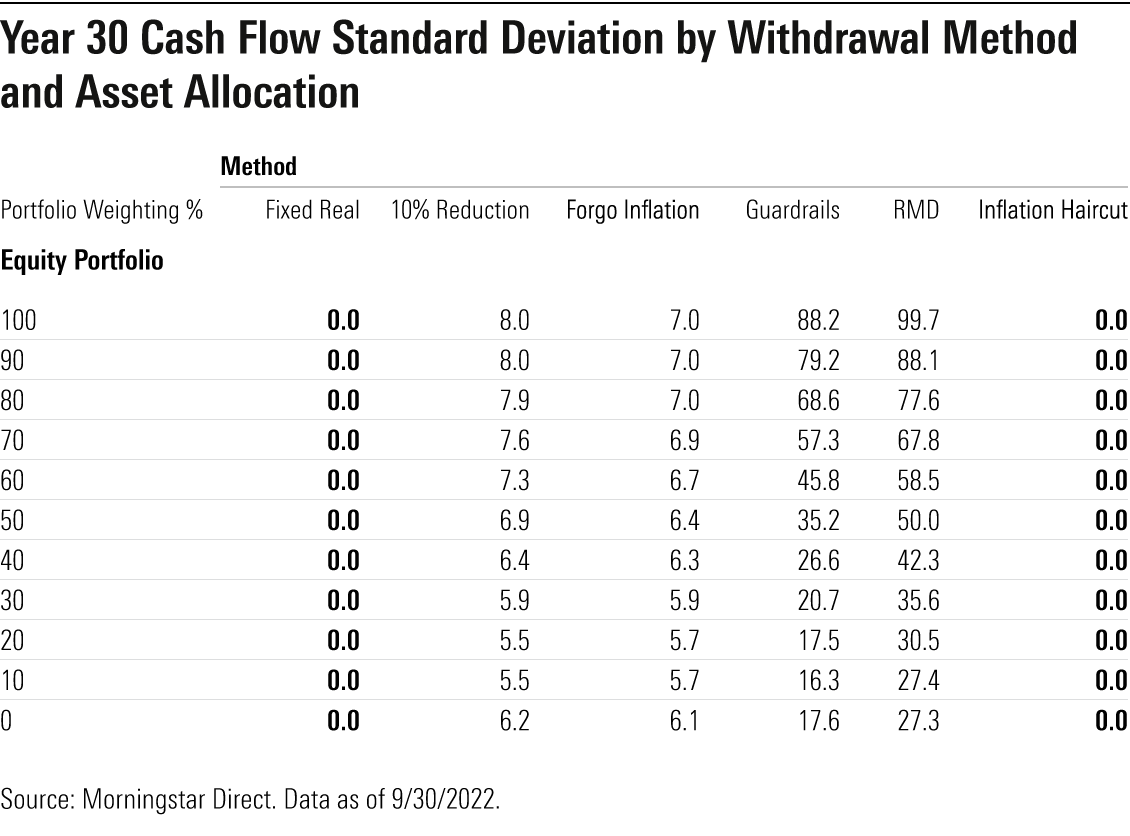

As with all of the dynamic systems, the major trade-off of the guardrails system’s higher withdrawal rates is that retirees need to be able to deal with some variations in their annual cash flows. Whereas our base-case spending system leads to a pattern of fixed real withdrawals with no volatility in cash flows, the guardrails method had a relatively high level of variability in its income stream. The standard deviation of its cash flows was the second highest of the methods we tested; only the RMD method had higher cash flow volatility. Also, portfolios with higher equity allocations tended to have bigger swings in annual cash flows than more-conservative portfolios, as the high stock weighting triggered more frequent raises and cutbacks.

Guardrails also led to substantially higher cash flow volatility than was the case for strategies that entail forgoing inflation adjustments or taking a 10% reduction following a year in which the portfolio has declined. That’s because those strategies only impose spending changes when the portfolio value has declined. By contrast, guardrails may lead to a spending adjustment after both very good and very bad portfolio performance. In other words, the triggers for spending changes are inherently more frequent with guardrails than is the case with some of the other strategies, though few retirees would finding getting a “raise” in their paychecks to be disagreeable.

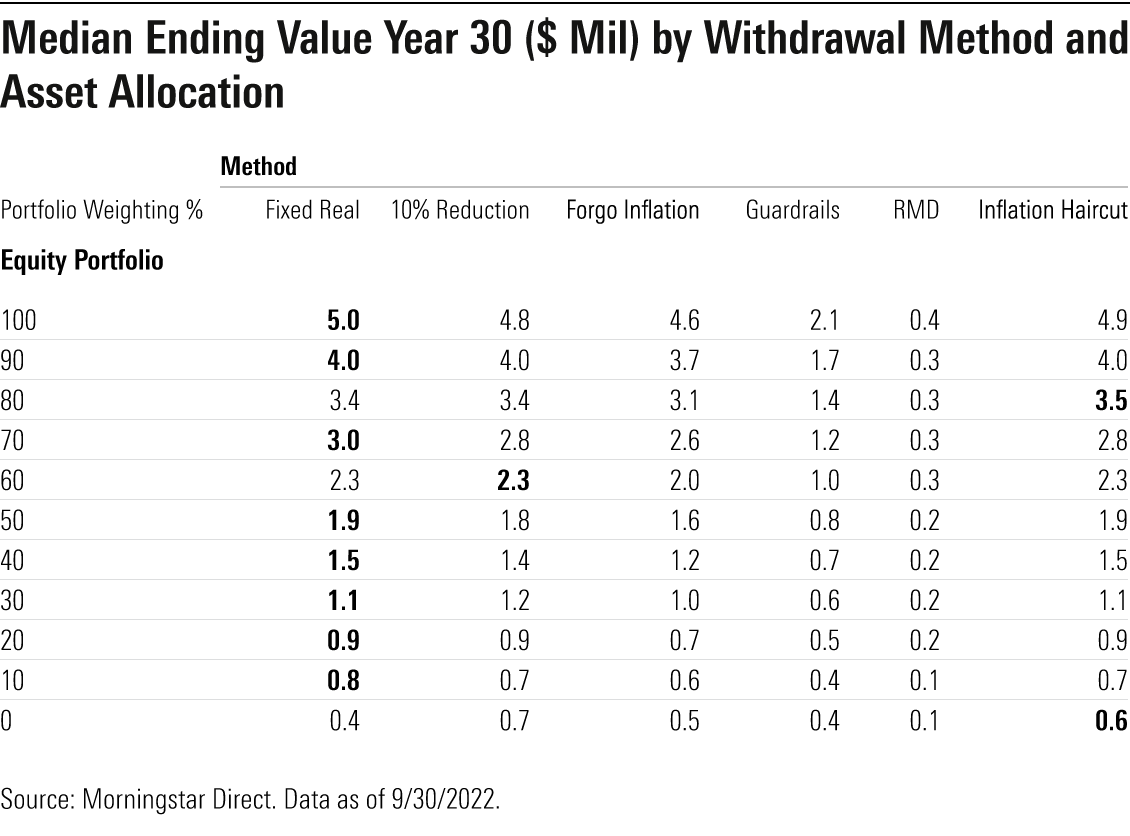

Additionally, the guardrails system tended to leave a lower residual balance after 30 years than some of the more static strategies. That’s because it encourages retirees to spend more when their portfolios perform well, but the trade-off is a lower median ending balance. Although the strategy resulted in more leftovers at Year 30 than was the case with the RMD method, especially for more equity-heavy portfolios, the guardrails system would tend to be most appropriate for retirees who prioritize maximizing spending over leaving a bequest to family or charity. Alternatively, retirees who wanted to prioritize a bequest while using the guardrails system could forgo larger withdrawals after good years.

Takeaways

For retirees aiming to wring more from their portfolios without radical adjustments to their standards of living, the guardrails system strikes a pleasing balance. While cash flow volatility is certainly higher than with a fixed real withdrawal approach or the two strategies that involve taking less after a losing year, it is substantially lower than the RMD method. Because the approach results in smaller final balances than most of the other strategies (only the RMD method had a lower median ending value), it will tend to be less suitable for retirees with a strong bequest motive. Finally, like all variable systems, the guardrails system requires ongoing calibration of the withdrawal amount. In contrast with a fixed real withdrawal system, the guardrails approach does not permit retirees to “set it and forget it.”

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)