Long Bonds Are No Longer for Fools

Prospects have improved for 30-year Treasuries.

Reversal of Fortune

I minced no words in April 2020′s “Long Bonds Are for Fools.” That article began, “Would you exchange $100,000 for a promise to receive $143,371 in April 2050? The question is rhetorical. The answer is ‘No.’ No matter how reputable the counterparty, 30 years is a very long time to wait, and a 43% cumulative gain is a meager return for your very long expenditure of patience.”

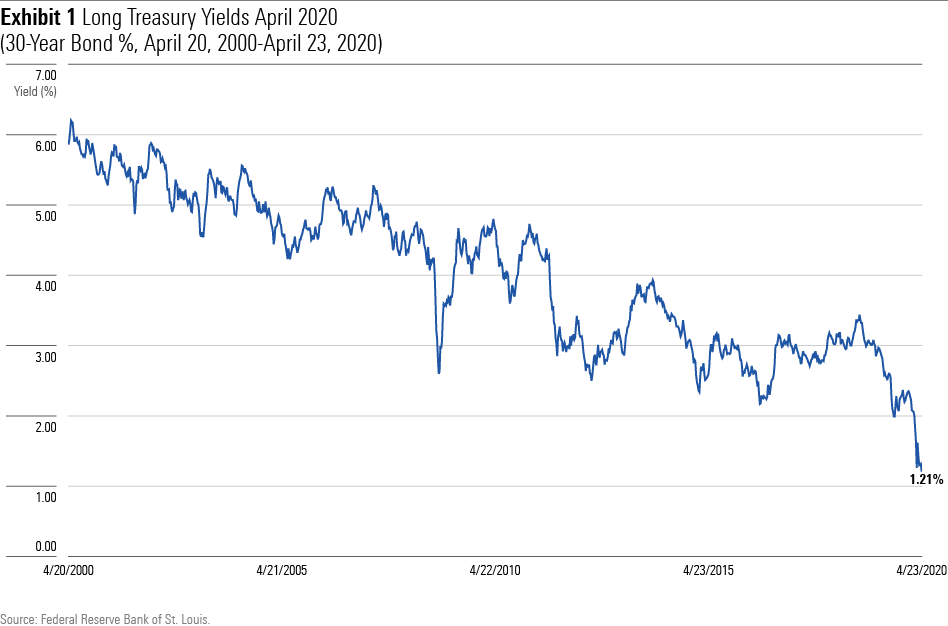

The analysis truly was that simple. As the following chart shows, the yield on 30-year Treasury bonds had dropped steadily over the previous two decades. That performance, along with the flight to investment safety sparked by the stock market’s spring 2020 crash, gave the impression that investing in long Treasuries would always succeed.

The good times were bound to end. Payouts on long Treasuries had become unsustainably low. Almost certainly, future inflation would be higher than the 1.2% yields that they provided in spring 2020. Long bonds would thus be losers in real terms. Institutions might have legitimate cause to hold them, to satisfy regulatory requirements or offset liabilities, but retail investors did not.

That much was clear. What I did not know—I can sometimes recognize the obvious, but I certainly cannot predict the unforeseeable—was that yields would bottom the day that article was published. (They had been briefly lower in the previous month, but they have not since touched their April 23, 2020, level.) Payouts on 30-year Treasuries have since tripled.

That dramatic improvement from the buyer’s perspective (the seller’s viewpoint is a much unhappier matter) makes long bonds once again worthy of consideration. They are by no means bargains. But neither should they be immediately dismissed, as with three years ago.

Total Returns

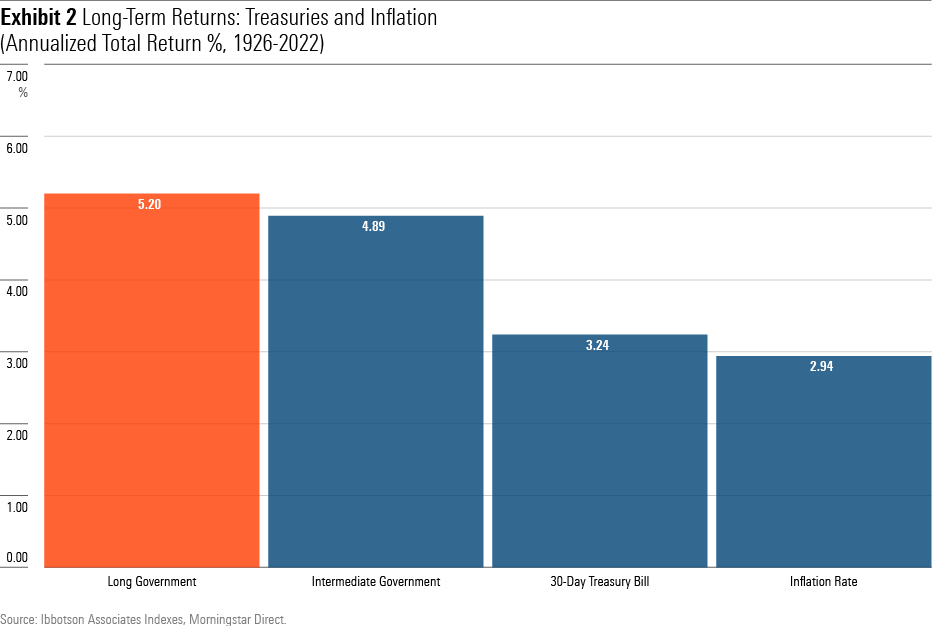

Setting aside speculation—the hope of selling an overpriced asset at an even steeper amount to an even greater fool—retail investors have two potential reasons to buy long Treasuries. One is for higher total returns. Over the 97 years for which Ibbotson Associates has tracked such results, long government securities have beaten their intermediate- and short-term rivals. They have also handily outpaced inflation.

This preliminary testimony urges two rebuttals. One is that the first half of the period, when U.S. currency was convertible into gold, is irrelevant for future considerations. Perhaps. However, if one dates the analysis to August 1971, when President Nixon suspended the Bretton Woods agreement, the conclusions still stand. Long government notes have gained more than shorter notes, which in turn have surpassed inflation.

Another rejoinder is that, over time, a bond’s total return usually ends up mirroring its starting yield. (This statement assumes the bond’s income is reinvested. If it is not, then the math is trivial for securities purchased at their par values: The total return exactly equals the yield.) As the current 3.6% yield on 30-year Treasuries is well below their 5.2% historic total return, past performance overstates future possibilities.

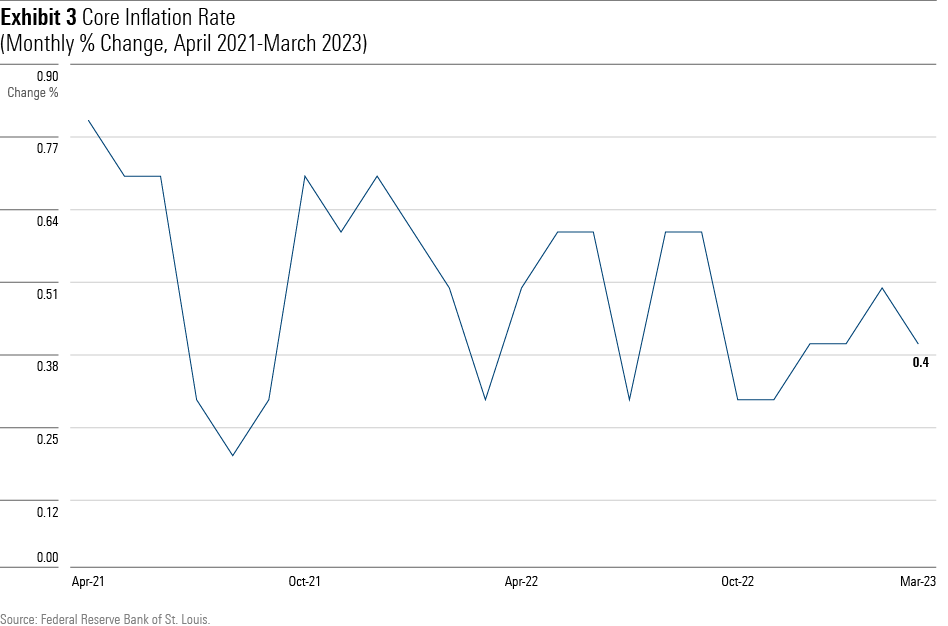

However, there is a counterargument. Although the times have indeed changed, in some respects they have changed for the better. From 1926 through 1981, the growth in annual U.S. inflation exceeded 10% in six calendar years. Since 1981, the score is zero. Last year did bring an inflation scare, but the recent decline in core inflation rates suggests that the modern version of the Federal Reserve will squash inflationary bursts more diligently than did its predecessors.

This, of course, is merely a hypothesis. But it is plausible. One can envision the Fed’s interest-rate hikes successfully pushing inflation near the institution’s 2% annual target, thereby making current long bond yields rewarding in real terms.

Recession Protection

The other reason to own long Treasuries is to limit portfolio losses when the economy weakens. Finding securities that hold their value is not difficult; any form of investment-grade cash accomplishes that, as does money stuffed under a mattress. But long Treasuries provide the additional possibility of recording outright gains.

More than a possibility, in fact. Through each of the five deepest recessions during the past 100 years—two of these have occurred within the past 20 years, so this is not just ancient history—long government bonds not only turned a profit, but also outdid Treasury bills. On four out of those five occasions, equities crashed. Long Treasuries have therefore offered strong protection against stock market declines caused by economic weakness.

Unfortunately, that statement does not mean that long bonds are flawless diversifiers. Far from it. When stock prices sink not because of recessionary concerns, but instead because of inflationary worries, long bonds provide no help whatsoever. They increase the pain rather than relieve it. In that sense, long Treasuries resemble alternative investments, such as gold or industrial commodities. They can alleviate stock market losses, but intermittently rather than reliably.

Wrapping Up

In recent years, I have advocated that investors use cash or short-term notes instead of long bonds to diversify their equities (along with alternative investments). That includes an article from last summer, which acknowledged the surge in long Treasury yields but panned them nevertheless. Their payoffs were still too low, I argued, and inflation was raging.

Since then, yields have risen further, while inflation, although still uncomfortably high, appears to be receding. That combination compels me to release long Treasuries from their penalty box.

Would I buy them myself? Probably not. I am optimistic enough about the Federal Reserve’s resolve to believe that a 3.6% yield will make for a small positive real return, but not so optimistic as to bet my future on that event. Thirty years is an awfully long time to be locked into a below-market yield, should that prove to be the case.

But for the first time in several years, one can at least make an argument for long Treasuries. That is a welcome change.

Correction (April 14, 2023): In a previous version of this article, the $100,000 figure in the opening paragraph was incorrectly stated as $10,000.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)