Pay Close Attention When Selecting an Emerging-Markets Bond Fund

Passive doesn’t mean straightforward in this market.

Emerging-markets debt is not for the faint of heart. The asset class struggled during the coronavirus shock in early 2020, then briefly but victoriously rebounded, only to precipitously fall again in 2021 as geopolitical tensions and U.S. interest rates rose. Yet performance perked up in the final stretch of 2022, turning net flows positive as investors again grew more comfortable with the asset class.

The easiest way to obtain exposure to emerging-markets debt is through broad index exchange-traded funds. Even if investors are content with this approach, the quirks in this market can still complicate picking a strategy. Choosing between debt denominated in local or hard currencies can translate to vastly different risk exposures, while each fund has its own idea of what exactly constitutes an emerging market.

Local or Hard Currency?

Emerging-markets debt can be denominated in either the local currency of the issuing country or hard currencies such as U.S. dollars or euros. This simple distinction can make a vast difference to an investment’s risk/reward profile. Hard-currency emerging-markets debt tends to carry higher credit risk than local-currency counterparts. Issuers from smaller economies, often with lower credit ratings, might issue bonds in hard currency to entice foreign capital.

On the other hand, more-stable economies with sufficient resources can better afford to issue debt in their local currency. Returns on local-currency debt depend more on local economic conditions, interest rates, and inflation. Investors often use it to express opinions on exchange rates, while hard-currency debt remains a purer play on credit spreads and interest-rate risk.

The incentives between issuing local- or hard-currency debt also led to different geographical adoption of each approach. Certain countries, such as South Korea, Thailand, and the Czech Republic, have very little sovereign debt outstanding in U.S. dollars, as they prefer to issue in their local currencies. On the other hand, the local-currency debt of Middle East nations is mostly excluded from broad local-currency indexes at this point. Despite being a top region in hard-currency portfolios, their bonds are mostly absent from local-currency ETFs.[1] Only roughly half of hard-currency and local-currency portfolios are in overlapping countries, making the two strategies distinct even without the currency risk implications.

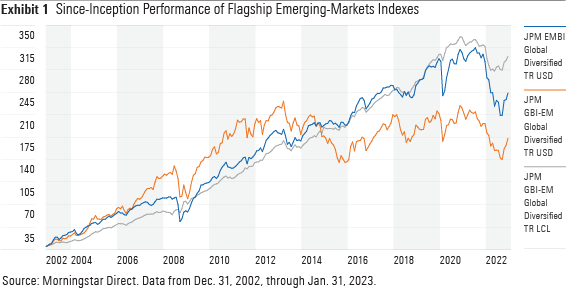

Exhibit 1 compares the performance of flagship emerging-markets debt indexes from JPMorgan. The JPM EMBI Global Diversified Index tracks U.S.-dollar-denominated debt and displays returns in dollars, while the JPM GBI-EM Global Diversified Index tracks local-currency debt, with one version displaying return in dollars and one in local currencies.

The return difference between the two indexes tracking local-currency debt reflects the movement of the U.S. dollar against emerging-markets currencies. The dollar weakened throughout most of the 2000s, translating to a sizable gain for investors converting returns into cheaper U.S. dollars. However, the dollar surged during the 2010s, significantly eroding the dollar return for investors holding local-currency debt.

The hard-currency index, on the other hand, mostly exhibited performance patterns similar to the local-currency index calculated in local currency. The only exceptions were periods of heightened credit stress, such as during the initial coronavirus shock or the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022. More exposed to smaller countries with higher credit risk, the hard-currency index fell much further than its local-currency counterpart during these periods. Overweighting larger, more-stable developing economies, such as South Africa, China, and Mexico, acted as ballast for the local-currency index during the market tumult. Ultimately, investors must choose which type of risk they would like to play a central role in their emerging-markets bond exposure.

Where Are the Emerging Markets?

Different index providers define emerging markets differently. Currently, JPMorgan and Bloomberg disagree on the classification of South Korea, which has long been a controversial case that also divides equity index providers. JPMorgan excludes the country from its investable local-currency sovereign index, the JPMorgan GBI-EM index series. Meanwhile, exposure to South Korean won-denominated debt stood at 12% for the Bloomberg Emerging Markets Local Currency Government Diversified Bond Index. Excluding a large market like South Korea can cause vast deviations between each index’s performance. For example, the Bloomberg index was cushioned by solid returns from South Korean debt when emerging-markets debt struggled between 2013 and 2015, allowing it to manage the period better than the JPMorgan index.

Even indexes from the same provider have different parameters for classifying countries as emerging markets. JPMorgan’s hard-currency corporate index, the JPMorgan CEMBI Broad Diversified Core Index, includes South Korea and Taiwan in its lineup, but its local-currency sovereign counterpart does not. The former maintains a specific list of eligible emerging-markets countries, while the latter defines emerging markets by their gross national income per capita or index purchasing power parity ratio.

Fund sponsors can also diverge from their index providers on the inclusion of certain markets. After Bloomberg started including local-currency Chinese debt in its index in 2019, Vanguard opted for a modified version of its Bloomberg fixed-income indexes to limit exposure to Chinese debt. As a result, Vanguard’s bond funds have lower exposure to Chinese bonds than funds tracking the uncapped versions of the index.

Vanguard isn’t the only fund provider wary of concentration risk in emerging markets. Most major fund sponsors, including Vanguard, choose indexes with a country-weight cap for their emerging-markets debt offerings.

This practice limits outsize exposure to any single country at the expense of full market representation. Though it tilts the portfolio toward smaller economies relative to the opportunity set, this approach serves as a guardrail for the high level of geopolitical tail risk in emerging markets. Events in recent years serve as a reminder of the importance of geographical diversification in this market. High-impact events, such as the fallout from China Evergrande Group and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, came with major consequences for countries directly involved as well as economies with close ties.

Choose Your Adventure

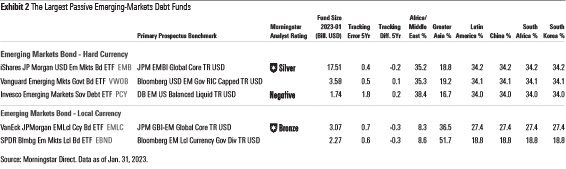

Exhibit 2 displays the largest passive funds in the emerging-markets bond and emerging-markets bond local-currency Morningstar Categories. Emerging-markets debt funds tend to have higher tracking error than most domestic U.S. bond funds because of the less-liquid markets and higher operational friction involved. Nonetheless, there are still a few sensible options for international-minded investors, notably iShares JPMorgan USD Emerging Markets Bond ETF EMB. The fund has outpaced its category average by 1.24 percentage points annualized since inception, with similar volatility.

[1] Saudi Arabia has started issuing more riyal-denominated debt in recent years. However, major emerging-markets debt index families have yet to grant them entry, except for FTSE.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)