The Moral Hazards of Banking Keep Increasing

No size, it seems, is now too small to fail.

High-Wire Acts

The banking industry is intrinsically perilous.

To start, banks cannot earn decent profits without being highly leveraged. After paying their overhead, banks have negligible margins. For example, regional bank Huntington Bancshares HBAN returned a mere 1.19% on its assets in 2022. Shareholders will not accept such low profitability. Consequently, Huntington employed 11.75 times leverage, to boost its return on equity to a respectable 13%. In contrast, Toyota TM carried a 2022 leverage ratio of 2.58, and Microsoft MSFT one of 2.19.

Banks are also economically sensitive. In that condition, of course, they are not alone. So is Toyota (although not so much Microsoft), as are many other businesses. What makes banks different is that their sensitivity is partnered with extreme leverage. They not only suffer when their customers do, but owing to their indebtedness, they have little maneuvering room when such events occur.

Exacerbating the danger is the tendency for bank executives to follow pro-cyclical policies, by assuming more loan risk during boom times, while becoming cautious only after the bad news arrives. Their finances would be sturdier if they did the opposite. Again, banks have plenty of company, as CEOs in other sectors tend to behave similarly. But again, banks are more vulnerable, owing to their leverage.

As shown by the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, the industry is not only threatened by sinking economies, which cause loan defaults, but also by its opposite—economic growth. In fourth-quarter 2022, United States GDP grew by an annualized 2.7%, chaperoned by the lowest unemployment rate since the start of the Nixon presidency. Boom times! However, not necessarily for banks, some of which have suffered sharp losses in their bond portfolios.

Crowd Effects

Most of these difficulties are controllable if the banks retain their clients. But often they do not—and for a logical reason. Should there be concerns about Toyota’s or Microsoft’s viability, those companies might be shunned by their vendors. But their customers could not sink them, because those companies do not hold client assets. However, banks do, thereby creating the incentive for customer panic. The first depositor to redeem will certainly be repaid in full. The 10,000th may not be.

(While insurance and mutual fund companies also hold other people’s money, the circumstances are different. With most insurance policies, holders can opt against renewing the contract, but cannot cash out. For their part, mutual fund shareholders need not rush to the door because their assets are separately custodied. Their money will be safe, even if sponsoring fund company is not.)

Finally, banks produce financial contagion, as well as suffer from it. To be sure, other businesses also cause ripple effects. Every company’s demise creates problems, as employees lose their income and vendors their revenue. However, because banks hold other people’s money, their failures reverberate. Panic begets panic.

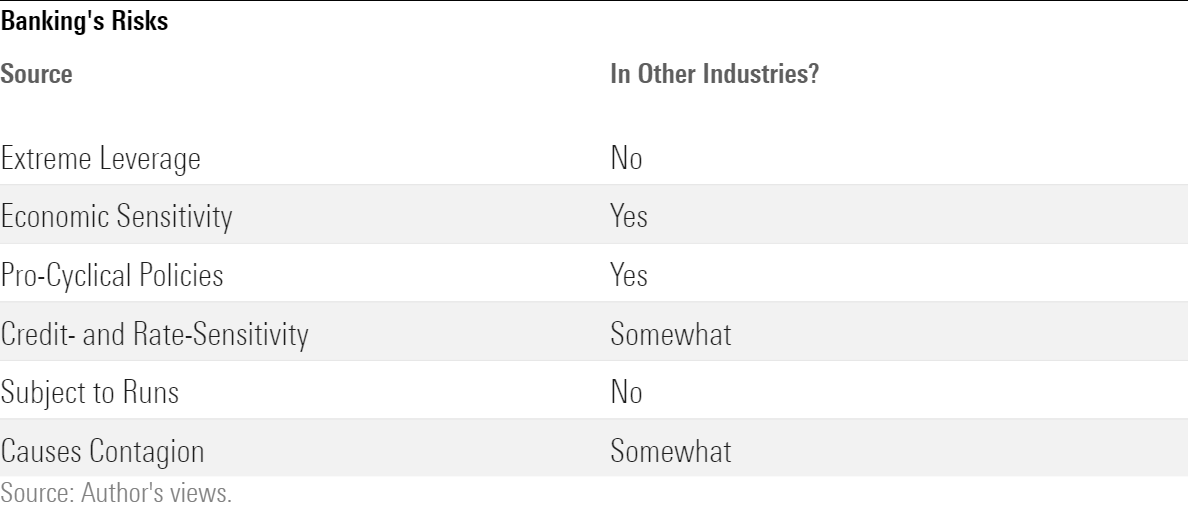

The following table summarizes the primary risks of the banking industry, along with the extent to which they are shared by other sectors. It’s quite a list.

Government Policies: Two Extremes

How should governments manage these threats? One solution is to abstain, by keeping the private markets private. The U.S. has never adopted a pure version of this approach, as it has always mandated minimum capital requirements, but it’s certainly true that early banking laws were looser than they are today. Regulations tightened with the launch of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913, and then even more following the Great Depression.

Another possible response is to take the opposite tack, by abolishing private banking and placing the state in charge. Under this arrangement, the bank can always meet its obligations, because it prints the money by which its depositors will be paid. Unfortunately, state control often leads to other problems, not the least of which is that the currency often becomes hopelessly devalued.

The lightly regulated approach has some merit. Although sometimes giving bankers a relatively free hand has resulted in ongoing banking scandals—for example, in the U.S. before the Civil War—on other occasions that strategy has been relatively successful. Be that as it may, there is no political appetite for its return. Nor will U.S. banking ever be nationalized.

The Middle Ground

Which brings us to the current regulatory policy. The U.S. government permits private banking, but with strict oversight. In doing so it employs both the stick and the carrot. The stick consists of bank examinations, mandated FDIC payments, and capital requirements. However, the regulators give as well as receive, both by helping troubled banks to find a buyer (as with 2008′s Washington Mutual) and by reassuring depositors during crises.

The latter is now much in evidence. With both Silicon Valley and Signature, the FDIC took the unusual step—I have not yet been able to determine whether its decision was outright unprecedented, although I believe that to be the case—of guaranteeing not only deposits covered by FDIC insurance plan’s $250,000 maximum, but also amounts above that figure. All customers will be made whole.

In essence, regulators have accepted future uncertainty for current peace. Knowing that the Treasury Department has already protected those who did not technically qualify for FDIC reimbursements, bank customers who exceed the insurance limit are that much likelier to take future chances. If the yield on their bank account seems unsustainably high, why worry? Should worst come to worst, the government will come to the rescue, as it did with Silicon Valley Bank.

Moral Hazards

Such has been the Treasury Department’s general policy since Lehman Brothers imploded in 2008. As this author notes, Lehman’s bankruptcy is now viewed as “the match that started the [global financial crisis’] conflagration.” To prevent such future catastrophes, the Treasury Department has subsequently preferred bailouts to market solutions. It did so throughout 2020 and did so again this past weekend.

Such actions have ramifications. An economist at the Kansas City Federal Reserve found that the government’s 1989 decision to withdraw support from failing savings and loans affected their executives’ future decisions, by making them more cautious. The absence of a safety net does not eliminate risk-taking, especially with banks, which as we have seen post higher profits with greater leverage (and with higher-yielding loan portfolios). But it does curb aggressive behavior.

I write this column to clarify, not chastise. In my three-part Social Security series, I argue that reforming Social Security’s finance is not difficult. Doing so merely requires political willpower. In contrast, allowing banks the freedom to create the loans that are necessary for businesses and consumers to thrive, while minimizing the harm caused the industry’s failures, resists simple solutions. The path taken by the U.S. government, of permitting tightly regulated private banking, with oversight that prefers tranquility to eliminating moral hazards, is reasonable. But it does carry consequences for the future.

(Final note: In a column published yesterday, Bloomberg’s Matt Levine writes that government officials may believe that their decision to rescue all depositors of Silicon Valley and Signature did not increase the bank industry’s moral hazard, because although it rewarded depositors who exceeded the insurance limit, it punished the proper parties: bank executives and shareholders. That is a conceivable argument—but it is not a view that I share. Nor, as Levine’s article makes clear, does AQR chief Cliff Asness.)

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XLSY65MOPVF3FIKU6E2FHF4GXE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)