Why a Long-Term Bond Bull Is Still Bullish

Investors are underestimating the impact of the Fed’s unprecedented tightening on the economy, inflation, and the risk of a credit-driven crisis.

Many stock and bond market investors are fixated on the strength of the economy starting off 2023, the stickiness of inflation, and the likelihood of the Federal Reserve raising interest rates higher and keeping them there longer.

But one bond market veteran says investors are like pedestrians looking the wrong way on a one-way street.

Lacy Hunt, economist at Hoisington Investment Management Company, says the real risk that investors should be on the watch for is that of a recession later this year and even a potential liquidity crisis in the financial markets. Case in point: worries sparked by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

Most importantly, says Hunt, inflation should start to decline substantially. This combination should start taking bond yields lower by the end of the year.

The reason, he says, is that, while it may seem like the Fed’s interest-rate increases aren’t having much of an effect as of now, investors are underestimating the degree to which ripples from the Fed’s moves are slowly working their way through the banking system. And before long, Hunt says, they’ll start to have a meaningful effect on the broader economy, including on inflation.

“The Fed created this huge mountain of liquidity in 2020 and 2021,” says Hunt, who has been at Hoisington for 27 years, after stints as chief economist at HSBC Bank and at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. “They now have a vacuum cleaner on it … sucking out the liquidity and as it comes out of the vacuum cleaner and goes into the incinerator. The process is underway.”

Thanks to this aggressive effort by the Fed, “I think we’ll see the inflation rate begin to unwind and we’ll make considerable progress and moving toward the Fed’s target toward the end of the year.”

Watching the Supply of Money

Hoisington, which manages over $3 billion, has a narrower focus than most bond managers. The firm manages strategies that invest in long-term U.S. Treasuries, which means that their performance is closely tied to the ups and downs of interest rates. The Austin, Texas-based firm is manager on the $282 million Wasatch-Hoisington U.S. Treasury Fund WHOSX.

Hunt, for his part, also takes a different approach from many bond investors these days. Like most economists, he tracks the many widely watched economic indicators such as gross domestic product, the jobs market, and trade balances.

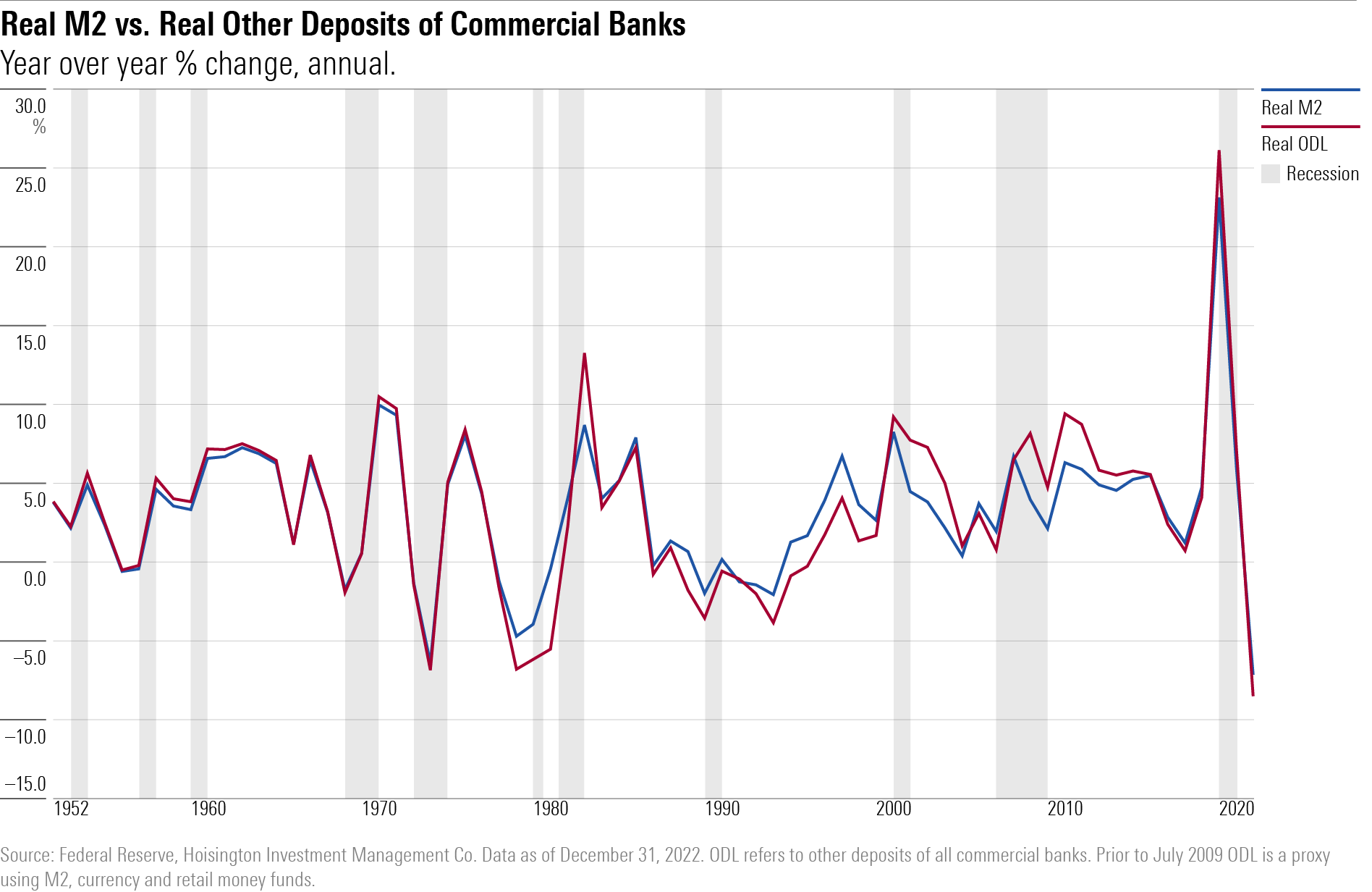

But Hunt also pays close attention to data that tracks the supply of money in the economy, as well as bank lending conditions and debt levels in the U.S. and global economies. In the 1970s and 1980s, data showing the ebb and flow of the supply of money in the economy was one of the main indicators that economists tracked for clues about the direction of inflation and Fed policy.

These days, few investors watch money supply data, such as the M1 and M2 series published by the Fed. But Hunt, whose career stretches back to the end of the 1960s, believes that there’s important information in the Fed’s data that can help investors look ahead.

Hunt’s preferred metric is a statistic published by the Fed known as “other deposit liabilities of the commercial banks,” or ODL for short. Hunt argues ODL is a particularly good reflection of the money in the banking system available for lending and for spending by households and consumers.

To understand the current dynamic, Hunt goes back to the Fed’s aggressive efforts to flood the banking system—and thus the economy—with financial liquidity when the coronavirus pandemic caused an economic lockdown.

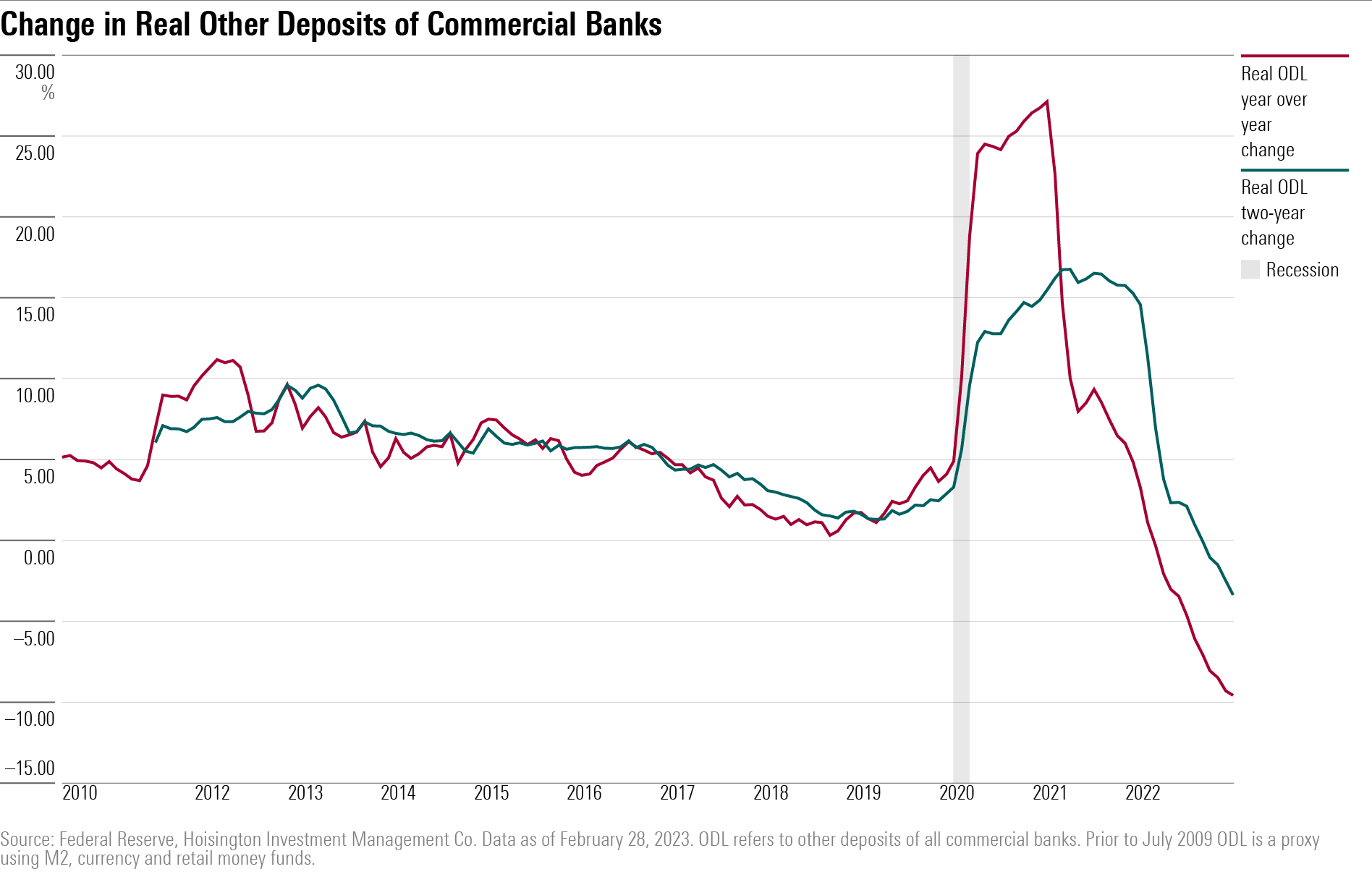

Historically, going back to the early 1950s, ODL has on average grown at just a 7% rate, Hunt says. In more recent years, prior to the pandemic, ODL growth has slowed, increasing at about a 1% or 2% rate per year as the Fed was tightening monetary policy until COVID-19 hit. Then came 2020 and 2021, when the Fed’s injections of liquidity into the banking system lifted ODL on average by a 20% rate.

An Unprecedented Siphoning of Liquidity

“Those were the two fastest years of nominal growth we’ve seen,” Hunt says. Even pre-World War II, “there is really nothing equivalent.”

Now, however, the Fed is siphoning out liquidity at an equally historic pace. In nominal terms, ODL has dropped by 3.6% in the past 12 months, a 9.4% decline when adjusted for inflation. “Those are the largest declines we’ve witnessed in the modern era,” Hunt says.

In terms of economic impact, for Hunt, the liquidity injection, along with the fiscal stimulus, was a significant driver of 2022′s inflation surge. “We had a very massive response (to the pandemic) in monetary and fiscal policy, which resulted in the worst cost-of-living crisis since the early 1980s,” he says.

Hunt, a longtime bull on the bond market, acknowledges that he was slow to see the inflationary impact of the Fed’s 2020 and 2021 monetary easing and resulting surge in bond yields. (Of course, it was the same for the Fed, which was calling the inflation surge “transitory.”)

“It was very difficult in the heat of the battle to weigh what was going on with regard to the monetary policy stimulus and weigh the effects of the pandemic,” he says. “As time has passed, and with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear the pandemic’s effects (on inflation) were relative mild and the monetary stimulation effect was extremely great.”

Inflation and the Straw That Broke the Camel’s Back

Still back in the first quarter of 2022, Hoisington’s shareholder review and outlook said, “Disaster is a strong but appropriate word that applies perfectly to the state of U.S. monetary policy.” Add in “the face of an unsurpassed breakdown in product delivery systems” and the Fed’s “money creation caused a massive imbalance between the demand and supply of goods.”

From there, the shareholder letter said, “reversing the past monetary and fiscal excess liquidity error will take time and persistence by the Fed.”

He compares the monetary stimulus that fueled massive inflation with the straw that broke the camel’s back. The camel—inflation—for a long time seemed to be unaffected by the Fed’s monetary easing in 2020. “So the fellow thinks he can put a little bit more on the camel’s back. But the camel collapses,” Hunt says, just as inflation—after years of lying dormant—surged in 2022.

Like a collapsed camel amid fallen straw, “when you have these monetary accelerations, it’s very, very difficult to unwind.”

In addition, “with these types of monetary swings … the Fed is essentially booming the (economic) booms and slumping the slumps.”

Rising Risks of Financial Accidents

Now, with the degree of tightening the Fed has done, Hunt says the reversal “will cause an inordinate weakness in economic activity” as we head into the second half of 2023.

Hunt says there are already signs that the flow of credit is being “choked off” to the economy. In the Fed’s January senior loan officer survey, on a number of metrics, banks are tightening credit standards to a degree not seen since the 2008 financial crisis (aside from a spike higher during the onset of the pandemic). Credit quality is also expected to deteriorate.

This environment, Hunt cautions, is ripe for a financial crisis. “When you have extreme monetary largesse followed by extreme monetary constriction, you lay the foundation for financial accidents,” Hunt says. Extremely easy money encourages more extreme risk-taking that relies on those easy money policies staying in place. Those risks get exposed when cheap money goes away, Hunt says.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, for example, may not have been directly tied to the Fed’s tightening, Hunt says, “but once you put liquidity in the system, it’s fungible, and when you withdraw it, it’s fungible and you don’t know who its getting extracted from.”

“That’s lurking in the background,” and should there be an element of a credit-driver financial meltdown somewhere in the markets or the economy, “that may change attitudes,” even if at present, “nothing seems to be broken.”

A Weaker Economy Ahead

For now, the markets seem to be focused elsewhere, largely shrugging off the actual impact of the Fed’s tightening, Hunt says.

To get a sense of where we’re headed, Hunt says he looks at the economic cycle as having five phases, with three up and two down. The three up parts of the cycle are revival, acceleration, and maturation. The two down parts of the cycle are ease-off and plunge.

He feels we’re in the maturation stage or the ease-off phase, with coincident indicators such as gross domestic product growth showing up as mixed but leading economic indicators turning down. Those include the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, levels of international trade, and the U.S. Treasury yield curve, which he sees as a reflection of the Fed’s monetary restraint.

“So, I think we are headed for a significantly weaker second half than we’ve seen,” Hunt says.

And from there, Hunt says the Fed could have a difficult job reviving the economy once it slips into a downturn. “One of the problems is that when you have excessive debt and poor demographics, and growth is below trend … what we’re going to learn is the central bank capabilities are ‘asymmetric,’ ” he says. “When the Fed is tightening against a heavily overindebted economy, they can get the job done. It may take them a while, but monetary policy will prevail. From my standpoint, though, when they need to reverse later on, I don’t think monetary policy will work well at all.”

“The past year and a half has been very difficult for those of us who are optimistic,” about the bond market, says Hunt. But given this backdrop, “I don’t think it’s a reason to surrender the view that ultimately the trending interest rates are lower.”

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/F2S5UYTO5JG4FOO3S7LPAAIGO4.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)