How to Balance Social Security’s Books

There may not yet be a will, but there are ways.

Social Security Reform

Friday’s column disputed the idea that Social Security resembles a conventional pension fund, with segregated assets for meeting its claims. That is how the Social Security Administration presents its books, but the practice is otherwise. Social Security resembles other government programs. Its tax revenues are spent in the year that they are raised.

(As a reader reminds me, Social Security’s current finances can also be regarded as an intergenerational wealth transfer, from younger workers to older retirees.)

Reframing the debate changes its time horizon. According to the Social Security Administration’s calculations, its trust fund will deplete circa 2035. No apparent worries. That gives legislators more than a decade to determine a fix. However, Social Security’s benefits expenditures have exceeded its revenue from payroll taxes every year since 2010. The program is already thoroughly in the red.

Whether that is a problem can be debated. Not all economists believe that the level of national debt is excessive. What’s more, Social Security is relatively self-reliant. In 2022, the Social Security program spent 8% more than it collected. For the rest of federal budget that figure was 34%. (This article further develops the claim that the government faces bigger challenges yet than Social Security.)

Does Social Security Need an Overhaul?

Let’s assume, however, that balancing Social Security’s books is imperative. How difficult is the task?

Truly, it is not. To be sure, if proposed in Washington, each of this column’s suggestions would be fiercely resisted, either by those who argue that no further revenue should be extracted from taxpayers, or by those who assert that retirees should be denied no benefits. The histrionics, however, disguise a congenial fact: Putting Social Security into the black would not require overhauling the system.

Before reviewing the what ifs, I should clarify my intent. It is not to present a cohesive solution that lawmakers should implement. Doing so would require a white paper, not a twice-weekly column. Rather, it is to convey scope. If, when finishing this article, you believe that squaring Social Security’s books can reasonably be achieved, my goal will have been accomplished.

My sources for this exercise are 1) the American Academy of Actuaries and 2) the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Each organization has developed an interactive tool that estimates the financial effects of adjusting Social Security’s regulations. Aside from the secondary effects that would arise from tax increases, these projections should be fairly accurate, because demographic effects can generally be anticipated. (For example, the Social Security Administration’s current financial forecasts look much like its Year 2000 effort.)

The results are presented as solvency percentages, defined as the amount necessary to support the Social Security system for the next 75 years. (This is not my favorite approach, as it invokes a “Social Security Trust Fund” that is more theoretical than actual, but it suffices. If the Trust Fund’s numbers sum, then Social Security’s revenue will keep pace with its costs.) No single adjustment reaches 100%. However, users can readily reach that mark by combining factors.

Reforming Social Security Revenue Sources

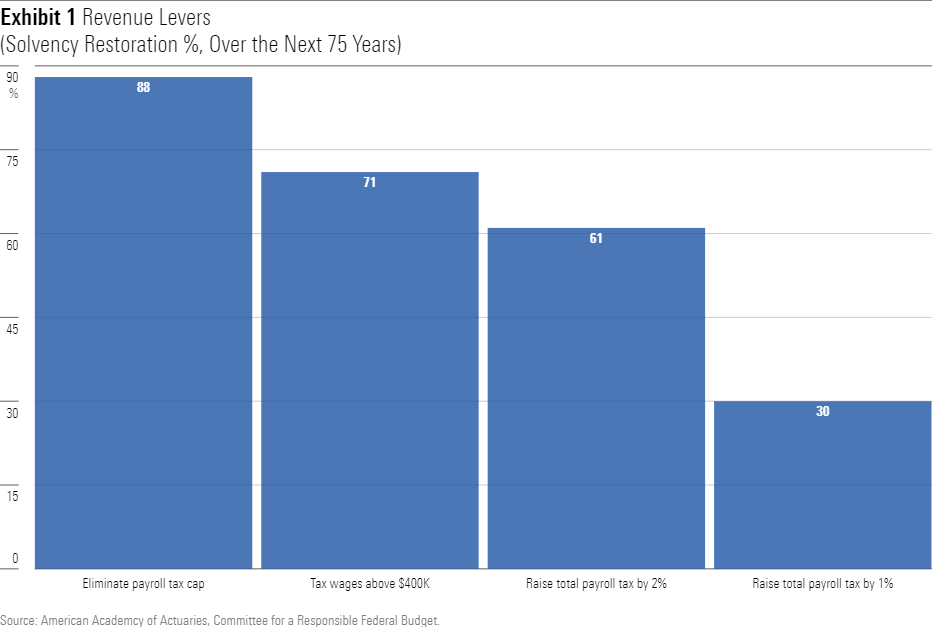

The following chart shows the major revenue options, which consist either of boosting the payroll-tax cap, so that higher-income workers subsidize the program, or by hiking the payroll tax, thereby spreading the burden. These effects are assessed independently. For example, the 61% solvency percentage that comes from raising the payroll tax by 2 percentage points (1 point for workers, 1 point for employees) does not assume a higher tax ceiling.

Entirely eliminating the payroll-tax cap, by levying the Social Security surcharge across all wages, has the single greatest effect of any proposal. That change alone would almost square Social Security’s books. Another suggestion is to suspend the payroll tax at the 2023 ceiling of $160,200, then resume the tax once the worker’s income surpasses $400,000. Effectively, that approach would consist of levying a Social Security surcharge tax on the top 1% of individual incomes.

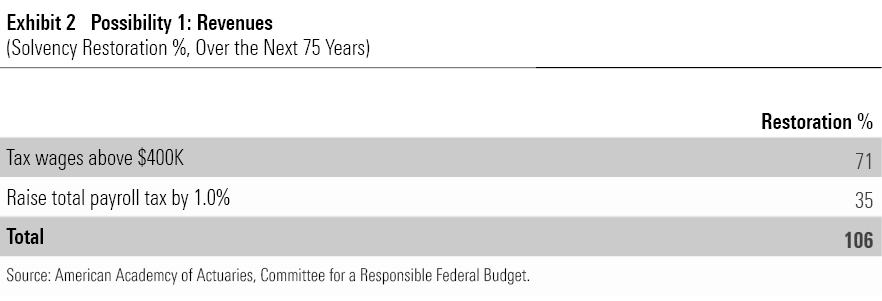

A combination of taxing wages above $400,000 and a 1% overall rise in the payroll tax (0.5% for workers, 0.5% for employees) would exceed the 100% target.

Reforming Social Security By Tweaking Benefits

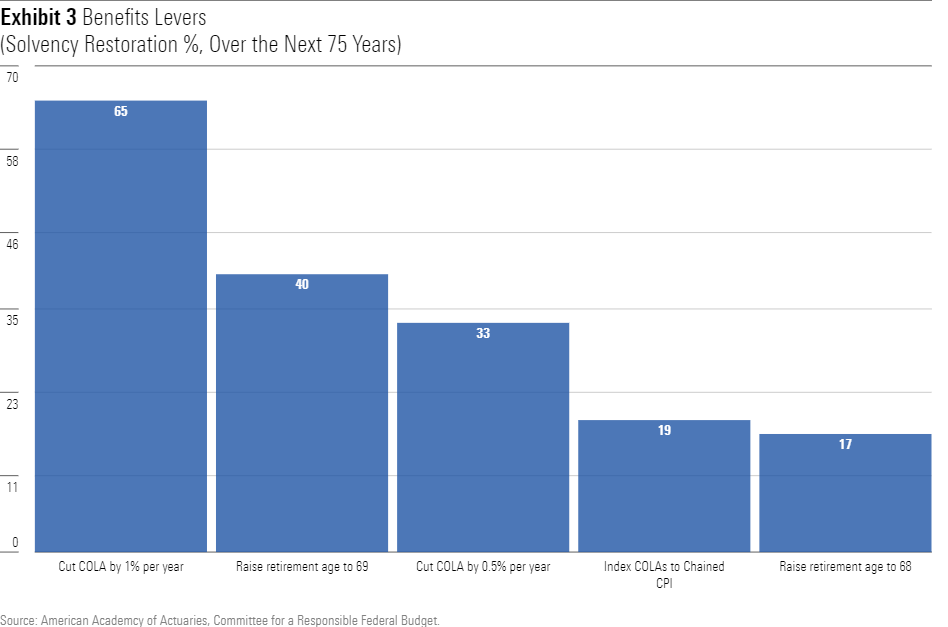

Broadly speaking, those seeking to shore up Social Security’s finances by trimming benefits have four choices: 1) maintain benefits for current recipients while cutting them for future retirees; 2) cut benefits to higher-income retirees via means testing; 3) lower the system’s cost-of-living increases; and 4) increase the full retirement age. As neither the first nor second approaches seem politically practical, I do not present them. But the final two offer many choices.

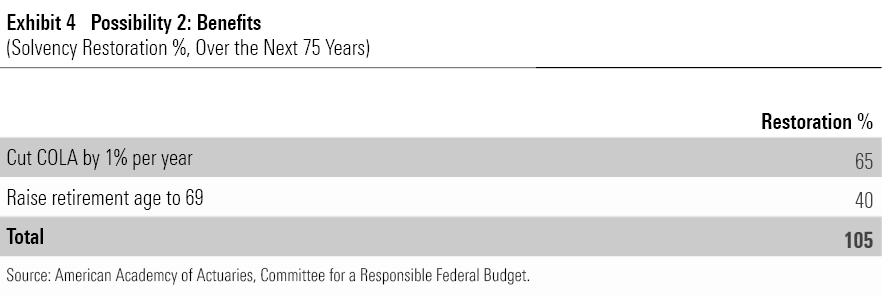

Below is a simple path for settling Social Security’s 75-year finances while not raising a penny in new taxes.

The Middle Ground

Some might regard these suggestions as extreme. While the Medicare tax faces no salary cap, it is much smaller than Social Security’s payroll tax. And reducing Cost of Living raises by 1 percentage point per year would slash the after-inflation income of long-lived retirees, although it also should be noted that apart from long-term healthcare costs, retirees usually spend even less over the years.

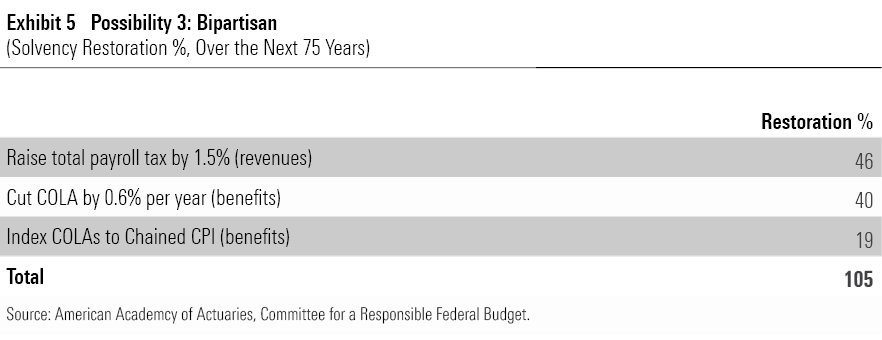

However, combining both revenue and benefit adjustments can create outcomes to which—it seems to me—only political intransigents would object. Consider, for example, the following proposal, which I do not view as radical. And if a bipartisan solution were to arrive, it would likely contain more moving parts, which would lessen the effect of each individual change.

In Conclusion

This discussion has been conducted at the highest of levels. Nevertheless, I hope that it has imparted its message, which is that balancing Social Security’s books should be achievable, once legislators believe that their political futures are better served by arriving at a solution than by attacking their perceived enemies.

Not that I know when such a day will arrive, of course. But at some point it will.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)